A Variety of Language Sources

British place names contain elements that can be traced back to the languages spoken by at least five quite distinct groups of people. Some of us may have been misled by the victory in World War II into thinking that Britain has never been ‘slaved’. However, the truth is very different from what we may want to think. The Welsh, the Scots, and the Irish are well aware that they have often been invaded by the English (amongst others). And a brief excursion into English history will reveal that the country has been invaded by the Celts, the Romans, the Anglo-Saxons, the Scandinavians, and the French. All of these groups contributed words which make up the place names we have today.

The Celts

The Celts were one of the many tribes living in Europe in the years before Christ. About 400 BC they began to leave Central Europe, possibly because of harassment from other tribes. The Celts from Northern France and the Netherlands crossed the Channel and settled in England. They were known as the Brythons (Britons). Later, about 350 BC, Celts from Southern France settled in Ireland. They spoke Goidelic (Gaelic). The Celts left behind names that are found most abundantly in the North and West (especially Wales and Cornwall). They also gave names to many rivers. Celtic names are often found in isolated spots which suggest that more remote groups remained Celtic-speaking long after other groups had accepted that language of the Anglo-Saxons. Celtic elements include:

aber – mouth of a river coombe – a deep valley

glen – a narrow valley pen – a hill tor a hill

There are very few names in East Anglia which contain Celtic elements. Most of the Celts probably fled the area when the Anglo-Saxon invaders arrived along the Eastern coast. Despite the survival of their Anglo-Saxon names Walpole and Walton were originally Celtic settlements and the first element of Dunwich is possibly linked to the Celtic word for ‘deep’, meaning something like ‘port with deep water’. The River Ouse probably gets its name from the Celtic word for water, and Lynn from the Celtic word for lake.

The Romans

After 300 years of calling the British Isles their own, the Celts were conquered by the Romans. Between 43 AD and 410, England was the north-west corner of the vast Roman Empire. Although the Romans occupied the country for over three centuries, they only left behind approximately 300 place names. This strongly suggests that the Roman administrators tended to use existing Celtic names. The main Latin elements in place names are:

castra (-chester, -caster) a Roman town, fort

colonia (-coln) a settlement

porta (-port) a gate

portus (-port) a harbour

strata (Strat-, -street) a Roman Road

As with the Celtic elements, there are very few Anglian names that contain Latin elements. Caister is derived from the Latin castra (camp) and this forms the second element of Brancaster. A few names contain the much later designations of Magna (Greater) and Parva (Smaller).

The Anglo-Saxons

The Angles, Saxons, and Jutes began to invade the British Isles in 449 AD. They came from Denmark and the coast of Germany and Holland. The Anglo-Saxons named their new country Engaland (the land of the Angles) and their language was called Englisc (what modern scholars refer to as ‘Anglo-Saxon’ or ‘Old English’. Most place names in Norfolk and Suffolk were originally given by the Anglo-Saxons. The Old English words that they used in the place names are far too numerous to list here (see my sources for further reading). I have given a few of the common Old English place-name elements below:

burna (-borne) a brook, stream

dun – a hill

eg (-ey) an island

halh – a nook, corner of land

ham – a homestead

hamm – an enclosure, water-meadow

ingas (-ing) the people of …

leah (-ley) a clearing

stede – a place, site of a building

tun – an enclosure, farmstead

well – a well, spring

worth – an enclosure, homestead

Cantley, Downham, Elmswell, and Wortham are good examples of Old English place names.

Cantley, Canta + leah – Canta’s clearing

Downham, dun + ham – Hill village

Elmswell, elm + wella – Elm-trees’ spring

Wortham, worth + ham – Homestead with enclosure

The Scandinavians

From 789 AD onwards, the Vikings from Denmark and Norway raided most parts of the British Isles. After much savage fighting they eventually settled down to live alongside the Anglo-Saxons. Modern Yorkshire, Derbyshire, Lincolnshire, Leicestershire, Norfolk and Suffolk became subject to Danish rule. The Scandinavian language, ‘Old Norse’, had the same Germanic roots as Old English so, over the years, the two languages mixed quite well. There are more Scandinavian names in Norfolk than in Suffolk, reflecting the fact that the early Viking invaders sailed up the River Yare and eventually made some settlements nearby. Some of the common Scandinavian place-name elements are listed below, although, as with the Old English elements, the Old Norse list does not claim to be anywhere near comprehensive (see my sources for further reading).

by a farm, then a village

dalr – a dale, valley

gathr – a yard gil – a ravine

holmr (-holm) flat ground by a river

lundr – a grove

thorpe – a secondary settlement, farm

thveit (-thwaite) a meadow

toft – a site of a house and outbuildings, a plot of land

Tyby, Barnby, and Lowestoft are good examples of Scandinavian place-names.

Tyby, Tidhe + by – Tidhe’s farmstead

Barnby, Barni, or Bjarni + by – Barni’s farmstead

Lowestoft, Hlothver + toft – Hlothver’s plot of land

The Norman French

The Normans invaded in 1066 AD, with the result that the language of the English Parliament was French for the next 300 years. However, like the Romans before them, they left a very small legacy of place names. This is because most of the settlements would have been well established by the time of their invasion. Their presence can occasionally be glimpsed in modern distortions of the names of foreign lords who may have owned land on both sides of the Channel. Thirteenth and fourteenth century lords owned the manors and gave their names to the places at Ashbocking, Carlton Colville, Stonham Aspall, Stowlangtoft, Saham Toney and Thorpe Morieux. Boulge comes from an Old French word meaning ‘uncultivated ground’.

Proceed With Care

Although driving through lanes trying to guess the meaning of the names on the sign-posts can be very entertaining (if the children are old enough, it is more fun than playing I-Spy) it is not always too productive. Even if you know that ham is probably derived from the Old English word meaning ‘homestead’, you wouldn’t necessarily be able to say for certain that Langham, for example, meant ‘something plus homestead’. This is because the Old English hamm (water meadow or enclosure) also comes out as ‘ham’ in modern place names. Only by looking at early forms can you distinguish between the two, and even then it is not always possible. In this particular case, Langham could mean either ‘long river meadow/enclosure’ or ‘long homestead’. Until the early spelling of the name is known (and by ‘early’ I mean at least the twelfth century or before), it is not possible to see which Celtic, Latin, Old English, Old Norse, or even Old French elements might form the name. Place-name scholars have to hunt through a variety of historical documents in order to record early spellings. The most famous of these sources is the Domesday Book.

Let me illustrate the importance of knowing the early spellings of a place. Superficially Hunston in Suffolk and Hunston in West Sussex and Hunstanton in Norfolk (often pronounced ‘Hunston’ by locals) appear to be very similar. However, their Domesday spellings reveal important differences.

Hunston (Sf), Hunterstuna *huntere + tun – Hunter’s farmstead

Hunston (W.Sus), Hunestan Huna + stan – Huna’s boundary stone

Hunstanton (Nf), Hunestanestuna Hunstan + tun – Hunstan’s farmstead

Similarly, you may be forgiven for thinking that Stanningfield contained some reference to ‘the people of …’ (ing) and that Troston doesn’t. Again, their early spellings reveal something very different.

Stanningfield, Stanfeldastan(en) + feld – Stony open ground

Troston, Trostingtun *Trosta + ingatun – Farmstead of *Trosta’s people

However, knowing that you may sometimes be wrong and that you will need to check when you get home, shouldn’t stop you having a guess. You should soon begin to get a feel for the way the names can be broken into two or three elements.

© James Rye 2021

See also Three Peoples on the Road

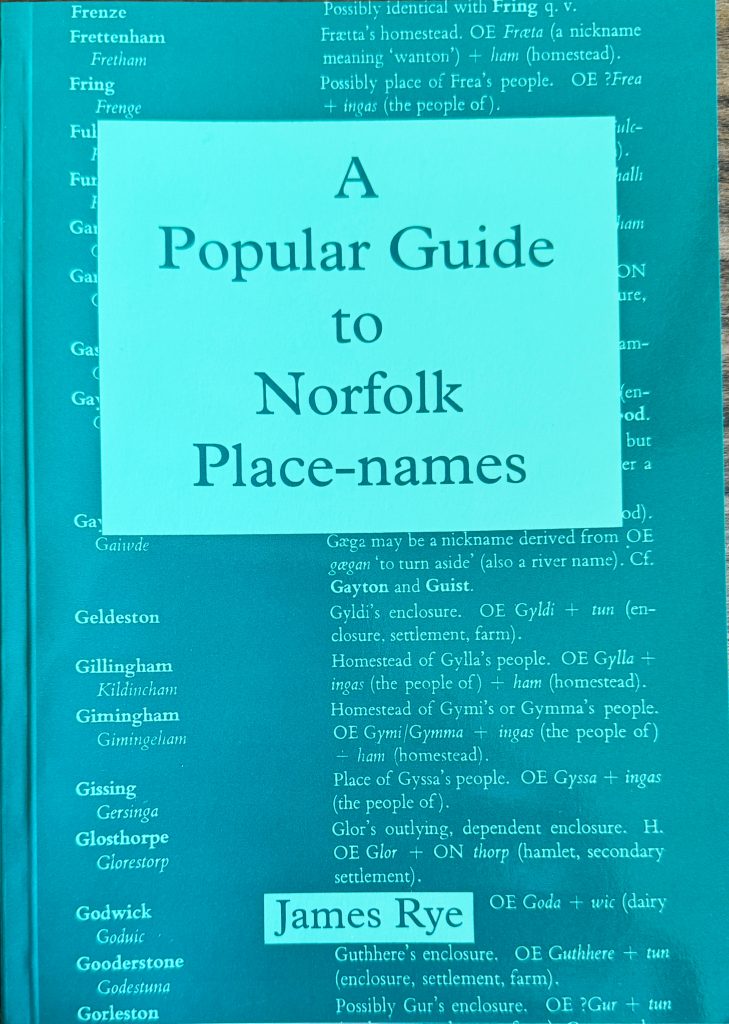

Buy a copy of James Rye’s Norfolk Place-name Book for only £3 + P&P. Contact the author to get your copy today.

Sources

- Cameron, K. (1961) English Place-names, Batsford

- Ekwall, E. (1960) The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-names (4th Edition), Clarendon Press

- Gelling, M. (1984) Place-names in the Landscape, Dent

- Harrington, E. (1984) The Meaning of English Place-names, Blackstaff Press

- Mills, A.D. (1991) A Dictionary of English Place-names, Oxford University Press

- Reansy, P.H. (1960) The Origin of English Place-names, Routledge & Kegan Paul

- Room, A. (1985) A Concise Dictionary of Modern Place-names in Great Britain and Ireland, Oxford University Press

- Rye, J. (1991) A Popular Guide to Norfolk Place-names, Larks Press

- Rye J. (1997) A Popular Guide to Suffolk Place-names, Larks Press