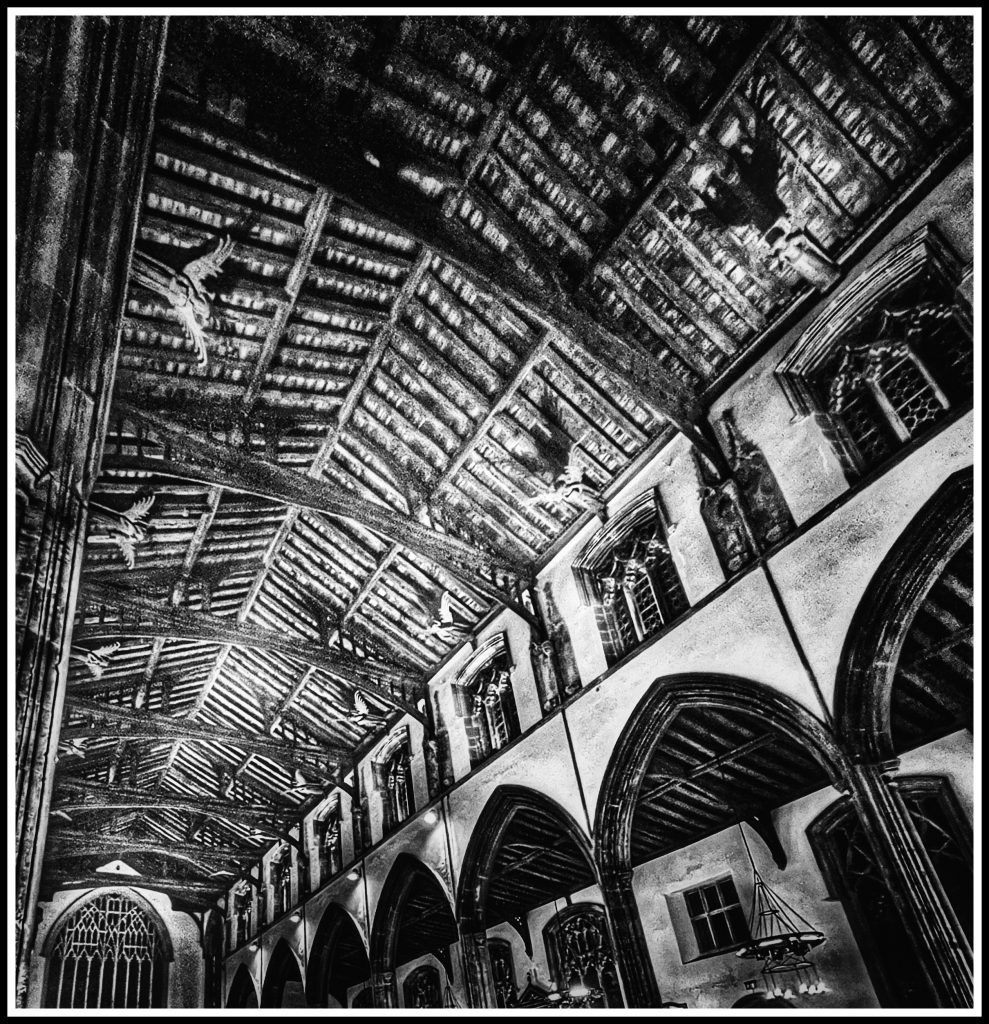

Angelic beings were important in late medieval life. They are often represented in English parish church art, especially in open timber roofs. You can see carved angels attached to beam ends, or to the intersections of the main timbers.

To the late medieval and largely illiterate lay worshippers, imagery was an important way to portray communal truth.

Photo © James Rye 2022

Angels In The East

In the sixth century Pope Gregory could joke about England as a whole (the land of the Anglo-Saxons) being the land of the Angles and of angels. However, the carved angels are particularly concentrated in the region of the East Angles (mainly in Norfolk and Suffolk churches).

Photo © James Rye 2022

Angel roofs flourished in the eastern region after the remodelling of the roof at Westminster Hall (c.1393-1399). Richard II’s hammer beam angels become the king’s guardians and display his royal arms.

Although the royal roof was a catalyst, its form was never precisely replicated. The concept of roof angels was adapted and developed according to the purposes and resources of local communities.

For example, the angels in the Wingfield St Andrew roof (1399) were the nobles and clerics who approved the overthrow of Richard II. They attended the opening of a new Parliament beneath its new royal roof in the autumn of 1399. Included in the roof are Michael de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk and Bishop Despenser of Norwich. There are other examples of roofs in the region celebrating local gentry.

The Angels In Lynn

Photo © James Rye 2022

However, the roof at St Nicholas’ Chapel in King’s Lynn followed a different course.

In order to appreciate the King’s Lynn angels it is useful to be aware of the historical context. It cannot be proved that background factors had a clear, direct influence on the creation of the angels, but they certainly add an interesting degree of local colour to the interpretation of the carvings.

On the other hand it could be argued that the angels were created just because local people with the money, the know-how, and the materials wanted to make them.

Perhaps the the two viewpoints are not mutually exclusive.

Background Factor One: Problems With St Margaret’s

The church of St Margaret, St Mary Magdalene, and all the Virgin Saints, was the parish church of Bishop’s Lynn (the former name of King’s Lynn) and had been started around the beginning of the C12th. St Nicholas’ Chapel was built during the second phase development of the town and wasn’t started until approximately fifty years later.

St Nicholas’ was technically a chapel of ease – built to enable the parishioners living at the other end of the town from St Margaret’s to make it easier for them to go to church. However, it’s dependency on St Margaret’s meant that it could not conduct christenings (not until 1627), or marriages, or perform the rite of purification after childbirth. People requiring those ceremonies had to go to the mother church (St Margaret’s). Legally St Nicholas’ Chapel was merely an appendage of the Parish Church.

Photo © James Rye 2022

In 1379 and again in 1432, coinciding, it seems, with new building campaigns, the parishioners of St Nicholas’ sued for the right to conduct their own ceremonies. Authority to perform these rites would have made, according to Margery Kempe, “the chapel equal to the parish church”. Margery Kempe’s father, John Brunham, who was mayor, opposed the petition the first time it was brought, and Margery opposed the second.

The reconstruction of the chapel and roof was one of the largest building programmes in Norfolk at the time, resulting in what today is the largest Chapel of Ease in England. One interpretation of the building is to see the structure as an architectural plea for it to be taken at least as equal to St Margaret’s.

Background Factor Two: Heresy In Lynn

In the early C15th the King (Henry IV) and the church leaders were nervous. The demands for social reform were growing following the Black Death, and this pressure had found some expression in the recent Peasants’ Revolt, 1381 (which had been firmly suppressed).

In addition to appeals for social reform, there were also calls for theological reform, centred around the teaching of John Wycliffe. Wycliffe was a prominent figure in the development of ideas against orthodox Catholic teachings. One of his many arguments warned that angelic imagery could mislead viewers into supposing that these spiritual beings were bodily material.

Photo © James Rye 2022

These demands for social and theological change were both united in the beliefs of a new movement whose followers were known as the Lollards. Lollards argued against praying to images of saints and crosses and going on pilgrimages. They did not believe that the bread and wine changed into the flesh and blood of Christ. They objected to unjust hierarchy based on family of birth. And they thought the church’s wealth was a sin and that its money should be redistributed to the poor.

Round about this time a local priest at St Margaret’s, William Sawtry, started to preach and defend Lollard beliefs. However, because of his persistence in spreading these beliefs, he became the first person in England to be officially burned alive for heresy. He was executed at Smithfield in London in March 1401.

The Bishop of Norwich with responsibility for Lynn, Henry Despenser, was known to be particularly vigorous in his pursuit of Lollards (he had imprisoned Sawtry at one stage). He would have almost certainly influenced the construction of the roof.

Given the context, one interpretation of the building is to see at least the the roof (built 1405-1410) as an affirmation and expensive celebration of orthodoxy in a time of challenge.

Lynn And Lincoln Angels

Margaret Cassell argues that the angels in Lynn derive their imagery more from the Angel Choir at Lincoln Cathedral (1280) rather than from Westminster Hall. As in Lynn, the Lincoln angels carry musical instruments and Passion attributes.

Photo © James Rye 2022

The angel bodies and heads are carved from a single piece of oak (probably from the Baltic), with arms, wings, and symbols on the front made separately. The carving varies in quality indicating that several workmen were involved in the construction. Three angels were replaced in the C19th using pine.

There are twenty-four angels, twelve on each side, in twelve bays. Ten are playing musical instruments (such as a psaltery, a recorder, a tambourine), and others hold artefacts with symbolic religious meaning (a bible, a hammer and nails, a crown of thorns). The tenor recorder is the first known sculptural representation of a recorder player (though the angel itself is a Victorian re-carving in pine of the original, c.1852). (St Nicholas’ Facebook Page has excellent close-up images of the angels.)

The attributes held by the beam angels at St Nicholas’ reference:

- Christ’s Passion (his suffering and sacrifice on the Cross);

- the Eucharistic sacrifice (in which the wine and bread offered at the Mass became the blood and body of Christ);

- and the eternal chorus of musical angels.

The spread of these motifs to other roofs suggests that conceptual links between the Passion, the sacrifice, the redemption and eternal Paradise were routinely made, at least on a visual level.

Afterwards: St Margaret’s Survives

When baptism was finally allowed at St Nicholas in 1627, the new font cost £13.

In 1989 the congregation at St Nicholas’ was very small, and the chapel was declared redundant. The Churches Conservation Trust now cares for the chapel and since 1996 it has been used as an Events’ Venue.

In 2011 St Margaret’s Church was designated as a Minster, reflecting its importance as a church in the area. The Church website explains: “St Margaret’s Church was made King’s Lynn Minster by the Bishop of Norwich in December 2011 in recognition that it provides a ministry far wider than that of a normal Parish Church. It is the civic church for West Norfolk and frequently holds services and events for the western part of the Diocese of Norwich. The historic and architectural significance of the building were also factors in the decision to make this a Minster. The title belongs to the building, so the parish served by the Minster is still called the Parish of St Margaret with St Nicholas and St Edmund, King’s Lynn.” (https://www.kingslynnminster.org/history/the-minster-story/)

© James Rye 2023

Book a Walk with a Trained and Qualified King’s Lynn Guide

Sources

- Allington-Smith, R. (2003) Henry Despenser the Fighting Bishop, Larks Press

- Cassell, S. https://www.academia.edu/68592208/Angel_Roofs_of_East_Anglia

- Parker, A. (2015) The Angel Roof of St Nicholas’ Chapel, King’s Lynn, Lecture given at King’s Lynn Town Hall (24/11/2015)

- Rimmer, M. https://www.angelroofs.net/

- Various (2017) St Nicholas Chapel, King’s Lynn: Discover More, The Churches Conservation Trust

- Windeatt, B. (Translator) (1965) The Book of Margery Kempe, Penguin (Modern English version)

[…] builds the extension north of the Purfleet with a new (larger) market place and a new church (St Nicholas’, which was to become the largest Chapel of Ease in England). The land was not part of the original […]

[…] now stands. (St James ceased being a religious building in 1548 and it collapsed in 1854). And St Nicholas was built from 1146 as the town expanded on the northern side of the Purfleet under Bishop […]

[…] The angels in Lynn derive their imagery more from the Angel Choir at Lincoln Cathedral (1280). As in Lynn, the Lincoln angels carry musical instruments and Passion attributes. […]