People listening to the news in modern times about pirate raids on vessels may be shocked to learn that at various times in the past, citizens and ships from King’s Lynn have been under threat from Barbary Pirates.

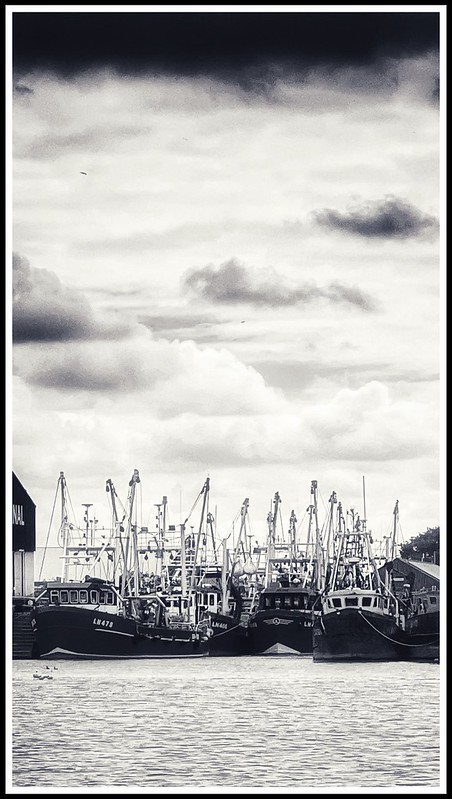

In 1570 an earth work fort was built in Lynn where the Fisher Fleet used to meet the River Great Ouse. It was built as a gun platform. There were also some buildings and a gate protecting access to the Fisher Fleet. In 1625, the same year that villages in Devon and Cornwall had been attacked by pirates, a 12-gun battery was established to defend the town against raids. It was a major part of the town’s fortification until 1839.

Photo © James Rye 2023

The town records show that an Admiralty Court was held at St George’s Hall in 1578, where 16 pirates were condemned to death. Four were executed at the Guanock, outside the South Gate, and the rest were taken to Norwich.

Pirates: Who Were They?

The pirates were known as Barbary Pirates and originally came from the coastal regions of central and western North Africa. Barbary is just another name for Berber. However, as time went on, they were joined by more and more renegades from other nations, with many of them converting to Islam. Some settled on the African coast; some of them set up base on Lundy Island in the Bristol Channel. Jacobean poems and plays contain references to pirates who had “gone Turk”.

Doubtless, some of these men were “freelance” thieves out to make a fortune, but most were technically “privateers” rather than “pirates” – that is they had been licensed (and often financed) by a particular ruler to attack the people and shipping of enemy countries.

Becoming a corsair was an attractive option to some Englishmen. The navy was contracting. The jobs at sea were few and low-paid, and naval life was tightly-disciplined. A legitimate life at sea would have been very unappealing for many. Although England had used its own privateers for years, peace treaties brought the demand for such skills to an end. However, in the Mediterranean, since Constantinople had fallen to Islam in 1453, rulers in the region were looking for ways to increase their wealth and pursue their war against the Christian West. Hence they were willing to finance men to disrupt trade and cause economic harm by capturing enemy crew and cargo.

European privateers worked in conjunction with the Berbers and introduced the latter to particular rigging and ship design which gave them the ability to chase ships in the Atlantic, outside the relatively calm waters of the Mediterranean.

The Barbary Pirates were active from the C14th to the C19th and regularly raided throughout the Mediterranean and along West Africa’s Atlantic coast. However, because of the enhancements to their shipping provided by their allies, the pirates were able to travel far into the North Sea. Some reached Newfoundland and Iceland. Others disturbed settlements on the coasts of France, Spain, Italy, Portugal, the Netherlands, England, and Ireland. Captives were taken back to Africa as slaves, where women were used as domestic servants or were put in the harems, and men were put to work on the land or made to row galleys.

By the mid 1600’s the situation was so serious that it threatened England’s fishing industry. In 1612 James I issued a general pardon to pirates in the hope of persuading some of the estimated 3000 English outlaws to change their ways. Admiralty records show that during this time the corsairs plundered British shipping pretty much at will, taking no fewer than 466 vessels between 1609 and 1616, and 27 more vessels from near Plymouth in 1625. Fishermen were unwilling to put to sea and leave their unprotected families at home.

Pirates: Shore Raids

Cornwall seems to have been particularly badly hit. In August 1625 privateers raided Mount’s Bay capturing 60 men, women and children. In 1626 St Keverne was repeatedly attacked, and boats out of Looe, Penzance, Mousehole and other Cornish ports were boarded and their crews taken captive. It was feared that there were around 60 Barbary men-of-war prowling the Devon and Cornish coasts and attacks were now occurring almost daily. In 1640 captives were taken to Africa from Penzance. In 1645, another raid by Barbary pirates on the Cornish coast saw 240 men, women and children kidnapped.

In 1631 Baltimore in Ireland was raided. An exasperated Charles I asked what had gone so wrong with the defence of the realm that two Algerian pirate ships could sail into an Irish harbour, abduct more than a hundred of his subjects (20 men, 87 women and children to be precise) and sail away again without anyone doing anything to stop them? Despite frequent pleas for help, William Gunter, who had lost his wife and 7 sons in the raid, never saw his family again.

Pirates: Lynn Prepares To Defend Itself

Although we cannot know for certain, it is highly probable that some sailors from Lynn had encountered Barbary pirates themselves on their travels (and at least had heard stories of them). Some locals sailors may even have been captured. The 16 executions of 1578, and the 1635 transportations to Marshalsea (see below) show there must have been direct contact with citizens of the town. Despite the uncertainty, during the early years of the C17th, some things were clear:

- The threat was real. It is estimated that in the early 1600s there were at least 35000 European slaves in North Africa. Coastal communities had started making collections of money to try to buy off attacks or redeem their local captives.

- Lynn was an attractive port at the end of the medieval period. Its trade links with the Hanseatic cities of north Europe had brought considerable wealth into the town. If it lost any inhabitants to the slavers, it would have money to ransom them back. And because it was a last dropping off port for the thousands of pilgrims regularly making their way to the shrine at Walsingham, there were likely to be plenty of people to seize.

- The town needed to be ready for attack and needed to go onto a war footing.

The town’s Hall Books in the King’s Lynn Borough Archive show exactly what preparations were being made 1613-1635.

- 1612, barrels of gunpowder bought, with a reference to “pirates of Tangier” off the coast

- 1619, reference to “pirates of Algiers and Tunis”, along with costs and charges

- 1619 payment of £100 towards the cost of sending a national fleet to Algiers to capture pirates, free slaves, and gain compensation for losses

- 1623, 12 muskets to be bought

- 1624, payment for 20 soldiers

- 1624 and 1625 saw the appearance of the Marshal of the Admiralty, possibly to preside over a Marine Court

- 1625 the petitioning of the king for 12 guns for battery (which were delivered)

- 1625, the “setting forth” of the 12 soldiers, also by proclamation of the king, the town to buy a barrel of gunpowder

- 1626, 3 barrels of gunpowder to be bought, the provision of 2 “shippes of warr” and a 3 one a grant of 40 marks per annum was provided for arming and training soldiers; also mentioned this year was the purchase of 4 barrels of gunpowder and 48 muskets for the town’s defence and the provision of muskets

- 1627, reference to Captains of the Foot Companies of the Town, and costs of a ship of war

- 1627 also saw money provided for 10 soldiers, their “improvement and apparel” and the purchase of pikes

- 1630, purchase of 2 barrels of gunpowder

- 1633, fitting out a ship of war, and again in 1635

- 1635 there was also this year the reimbursement of expenses for “conducting pirates to Marshalsea” prison near London Bridge

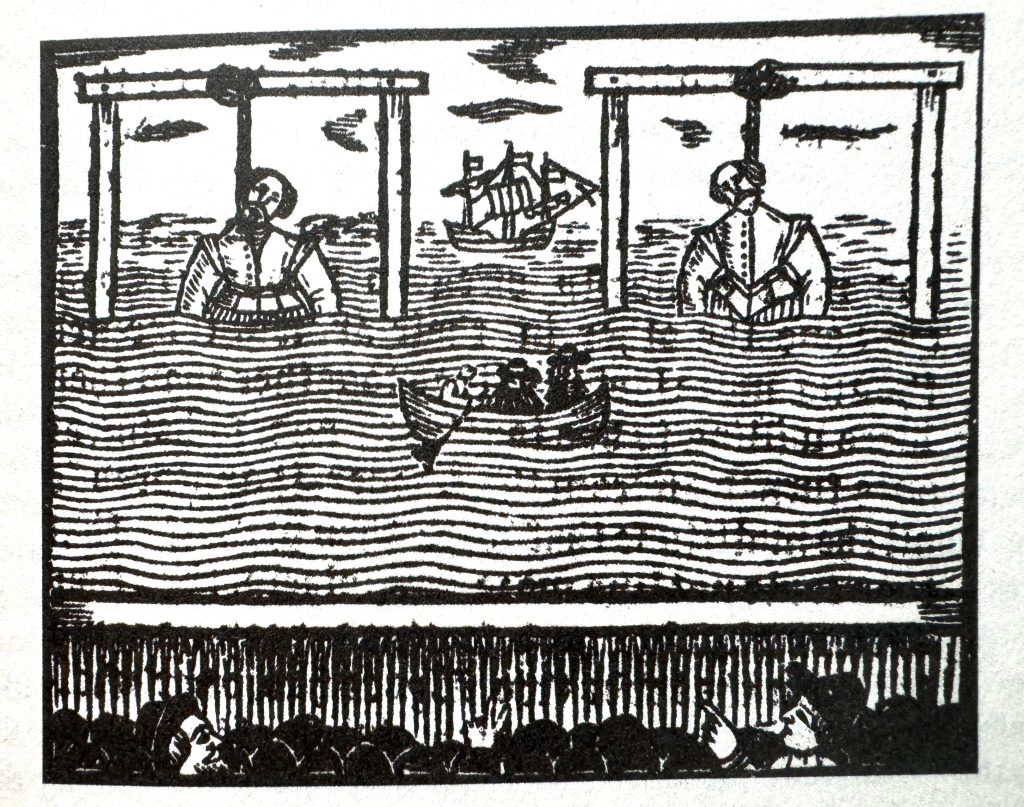

The threat of pirates didn’t really cease until the late C19th. It seems that capture and punishment by the authorities did little to deter them. Oliver Cromwell argued that all corsairs caught by the English should be taken to Bristol and slowly drowned. Sometimes they were executed by being burned alive or by being gibbetted with their bodies being left as carion. In 1609 in London several were hanged with their bodies left dangling until three tides had washed over them.

At the Congress of Vienna (1814-15) following the Napoleonic Wars, the European powers agreed that the Barbary pirates needed to be completely suppressed. France played a big part in helping achieve this by its conquest of Algeria in 1830 and its subsequent pacification during the remainder of the century. And throughout the Mediterranean corsairs were ultimately swept away by America’s need to protect its trade and by a tidal wave of colonialism from other nations.

© James Rye 2024

Book a Walk with a Trained and Qualified King’s Lynn Guide Through Historic Lynn

Sources

- Daily Telegraph (2017) Memory of Cornish coast dwellers kidnapped for slavery “culturally erased”, 30/12/17

- Eddison, J. (2013) Medieval Pirates: Pirates, Raiders and Privateers 1204 – 1453, The History Press

- In Our Time Podcast 09/11/23 The Barbary Corsairs

- Moore, G. (2022) The lives, apprehensions, arraignments, and executions, of the 19 late pirates, https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0787/11/4/82

- Tinniswood, A. (2011) Pirates Of Barbary: Corsairs, Conquests and Captivity in the 17th-Century Mediterranean, Vintage

- Valar, C. (2013) Sir Henry Mainwaring on the Prevention and Supression of Piracy, http://www.cindyvallar.com/Suppressionofpirates.html

- Webb, S. (2021) The Forgotten Slave Trade: The White European Slaves of Islam, Pen & Sword

- https://norfolkrecordofficeblog.org/2018/05/17/barbary-pirates-near-kings-lynn/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barbary_pirates

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/empire_seapower/white_slaves_01.shtml

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Barbary-pirate

- https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/Barbary-Pirates-English-Slaves/

[…] Pirates Threaten Lynn […]