If they think about it for a second, people are often puzzled by the name King’s Lynn. Most inhabitants of the town have no idea about the origin of the name. And some of the most common questions asked of King’s Lynn Town Guides are about the town’s name. What does it mean? How did it come about?

Is it King’s Lynn because Sandringham is close by?

Is it King’s Lynn because the town supported Charles I in the English Civil War?

Is it King’s Lynn because of the King John Cup?

The answer to all three questions is No. The truth lies much further back in history. And the name is best explained in three parts.

Part One: Lynn

The Mud

When William the Conqueror was asking his scribes to write down the details of his new kingdom in the Domesday Book (1085), the town of King’s Lynn didn’t exist. But the lynn or lin did exist.

Lynn is almost certainly derived from the Celtic word ‘llyn” meaning “tidal lake” or “body of water”. The area was even closer to the Wash (big tidal lake) than it is now. And a slow moving, tidal, relatively shallow, wide body of water would have covered a lot of the area on the west of the town. The buildings, had they existed then, between St Margaret’s Church and the present river bank would have been standing on mud in 1066.

There wasn’t a town but there were people on the banks. The Domesday Book records the existence of several saltings. Saltings where places were people were boiling the muddy, tidal water to obtain salt in order to preserve food. Over the years the unwanted sludge from the saltings would have been deposited on the river bank raising the land for reclamation. And in addition to meeting to buy salt, people also met to barter goods. So there were groups of people meeting on the edges of the lynn.

Part Two: Bishop’s Lynn

The Bishops, The First King (King John), and The Muddle

The town of Lynn was partly created because a bishop did something really bad that he regretted later. You can read the full story here: The Sinner and the Dragon: St Margaret’s, King’s Lynn. Basically Bishop Herbert de Losinga used his wealth to try and buy spiritual advancement. He later regretted it and asked the pope for a pardon. The latter was granted on the condition that he used his wealth to build three new churches – one at Great Yarmouth on the east of the County of Norfolk, one at Norwich in the centre of the County that was to become Norwich Cathedral, and one on the west of the County – St Margaret’s in Lynn.

De Losinga was told that he could establish a new town based around the new church, boundaried by the Mill Fleet to the south (concreted over since 1895) and the Purfleet to the north. Losinga was also allowed to have a market and was made the first Bishop of Norwich. The new town and church, started at the end of the eleventh century, was under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Norwich and was called Lenne Episcopi or Bishop’s Lynn, though I expect the locals still called it Lynn.

In 1135 the town had expanded eastwards (along what is now called St James’ Street) and a new chapel of ease (St James’) was built. Then in 1146 a new Bishop of Norwich, William Turbe, expanded the town on newland to the north on the land boundaried by the Purfleet to the south and the Fisherfleet to the north. Turbe built a larger marketplace and a second chapel of ease (St Nicholas’).

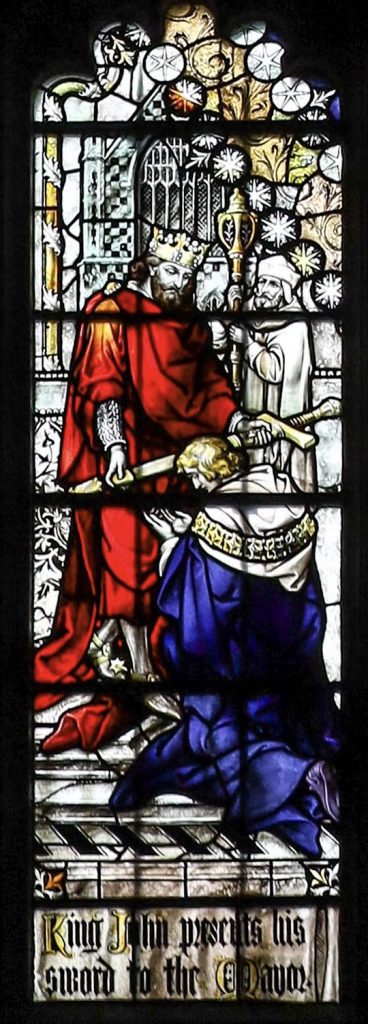

Lynn (or particularly Bishop’s Lynn) features as a significant footnote on three occasions in any history of King John (see Hostage Taking In Lynn). King John had a lot on his mind in 1204 having just lost virtually all of the English territory in France. However, he was persuaded by the new Bishop of Norwich, John de Gray (who was soon to become Archbishop of Canterbury) that the town would benefit from having a greater degree of freedom. The ability to make a few bylaws and raise a tiny bit of income would help the rapidly growing town. John agreed and in 1204 gave the town a charter with certain rights.

However, the exact details were not fully sorted out. Bishop’s Lynn was to have the same rights as the town of Oxford, but the Bishop of Norwich (and the Earl of Arundel) also were to continue to have rights (hence no name change). It was a muddle.

For over three hundred years two things clearly did happen. First, the town’s officers spent a lot of time travelling between Lynn and Oxford and between Lynn and Norwich trying to work out if they were allowed to do something or not. And on occasions the bishop would say, “No,” and the townsfolk would say, “But they can do that in Oxford!” The second thing that happened was that there was often increasing friction between Lynn and the Bishop of Norwich. On one occasion in 1377 this spilled over into a riot when the bishop visited the town and the rioters tried to kill him (see The Riot when Bishop Henry Despenser came to Lynn).

Part Three: King’s Lynn

The Second King (Henry VIII) Brings Freedom

King Henry VIII was did not have a good relationship with the Pope. He had separated from the Roman Catholic Church over his desire to divorce his first wife and declared himself Head of the Church in England. Henry had been excommunicated by the Pope in 1535. Although temporarily suspended, this excommunication was re-imposed in 1538 after Henry’s dissolution of the monasteries.

Although it would be wrong to argue that Henry’s major dispute with the Pope caused the change in Bishop Lynn’s name, it certainly helped it along the way. Cardinal Wolsey had visited the town in 1520 and been royally entertained by Lynn’s mayor. One can imagine that during the multitudinous courses of food, and as the wine flowed, the mayor was able to inform the Cardinal of Lynn’s little local difficulty with the Bishops of Norwich.

Henry was made aware of the situation and in 1524 he declared that he would deliver Lynn from “the tyranny of the Bishop of Norwich”. Lynn was given a new charter with greater rights to pass laws and collect income. And the town was also given a new name in a second charter in 1537 – Lynn Regis, or King’s Lynn.

Miscellany

- The town’s name has nothing to do with the Royal House at Sandringham. The Royal Family didn’t purchase the house until 1861, long after the town had its name.

- A Hunstanton aristocrat (Hamon Le Strange) managed to get the town to declare for the King in the English Civil War, but most of East Anglia was Parliamentarian and the town had chosen two Parliamentarian MPs at the time. And again, this all happened over one hundred years after the name of King’s Lynn had been established. See The Siege of King’s Lynn 1643 (1) – Which Side?

- The so-called King John cup was made in Flanders in the fourteenth century and is associated with Edward III. Lynn was still called Bishop’s Lynn at the time. It was the charter of 1537 that brought the significant name change.

- The west window of St Margaret’s Church has a bottom row featuring the key people in the history of Lynn’s name change. See King’s Lynn’s Contradictory Window.

© James Rye 2022

Book a Walk with a Trained and Qualified King’s Lynn Guide Through Historic Lynn

Sources

- Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/place/Kings-Lynn-town-England-United-Kingdom

- Hillen, H.J. (1907) History of the Borough of King’s Lynn, Vol.1, EP Publishing Ltd.

- History of Medieval Lynn: http://users.trytel.com/~tristan/towns/lynn1.html

- Norfolk Records Office: https://norfolkrecordofficeblog.org/2016/10/21/one-of-kings-lynn-borough-archives-earliest-documents-the-charter-of-king-john-to-the-burgesses-of-lynn-14-september-1204/

- Owen, D.M. (1984) The Making of King’s Lynn: A Documentary Survey, Oxford University Press

- Parker, V. (1971) The Making of King’s Lynn, Phillimore

- Rye, J. (1991) A Popular Guide to Norfolk Place-names, Larks Press

[…] history, but the town of King’s Lynn itself (originally called “Bishop’s Lynn” – see Why is King’s Lynn called “King’s Lynn”?) has a relatively late beginning. There was no quaint Celtic settlement that developed into a Saxon […]

[…] had many links to royalty. It was Henry VIII who gave the town part of the name it enjoys today (see Why is King’s Lynn called “King’s Lynn”?) Every medieval monarch usually stayed at the Augustinian Friary on their way to the shrine at […]

[…] Why is King’s Lynn Called “King’s Lynn”? […]