Francis Shaxton – King’s Lynn Smuggler

Francis Shaxton was a respected alderman in the respectable prosperous town of King’s Lynn. But when he was first elected by his peers to the mayoral office in 1569 he had already been stealing money from the tax collectors for a number of years. Lewis (2001) called him “The Greatest Smuggler in England”.

People often associate smuggling with dark nights, sandy beaches, and hoards of tobacco and gin hidden in old coastal church towers. Although King’s Lynn had its fair share of traditional smugglers (most notably Thomas Franklyn and William Kemball), Shaxton was in a completely different league. He operated by daylight in warehouses on the South Quay at the top of College Lane, near the Town Hall. His smuggling didn’t involve moving illicitly obtained goods, but in pretending duty had been paid when it hadn’t.

And he had a secret weapon.

Francis Shaxton’s Tax Fraud: Part One – The Cocket

Francis originated from West Bilney. Unfortunately his parents died of the plague in 1546 and the teenager became an apprentice to a cloth maker in King’s Lynn. Before long he qualified as a Master Clothier and also moved into the grain trade. He married and bought a house in College Lane with easy access to a warehouse directly on the quayside.

Shaxton’s smuggling deception involved the skilful use of the cocket. The cocket was a document bearing the customs seal for the port certifying that duty had been paid. It was essential proof of payment and had to be checked by the port’s Searcher before being given to the ship’s master to be retained for the voyage.

In order to succeed there were a number of things that Shaxton needed to control. The first problem was the port’s Searcher. He needed to agree that the amount of goods declared on the cocket were the same as the the amount of goods found in the ship’s hold. Robert Daniell was the Searcher for Lynn and he was paid 3s.4d. per cargo. Shaxton struck a deal to pay him £3 a shipment.

The second part of the major, ongoing fraud fell into place when a man called Richard Downes had a huge row with his father-in-law. The Port Controller was called William Ashwell. His daughter had married Richard Downes and Ashwell had got his son-in-law a job in the Custom House. Fortunately they argued and Ashwell got Downes fired. Downes left his job with a chip on his shoulder an a desire for revenge against his father-in-law.

One day Downes was walking by the Custom House when he saw a number of unattended cocket seals on a table. He took them and persuaded a Dutch goldsmith friend to copy them before discreetly returning them. Armed with the counterfeit seals, and his knowledge of the Custom House workings, and having a desire for revenge, Downes began to wonder how he could make some money.

Shaxton and Downes met in 1566 and struck a deal whereby Shaxton paid Downes 13s.4d. for each counterfeit customs document, potentially giving Francis carte blanche to export grain duty free. Shaxton also had close contacts with Thomas Sidney, a wealthy and important Lynn landowner. In addition to being the port Customer (someone with responsibility for seeing that the correct duty was paid) he also regularly had grain cargoes to be shipped and proved susceptible to the prospect of illicit gains.

Francis Shaxton’s Riches And Property Empire

For years Shaxton would happily declare away, without paying duty on all his goods (while being careful enough not to draw attention to the fraud). This enabled him to get rich and undercut his rivals.

It is difficult to assess the extent of the total value of the fraud. And clearly Shaxton was not the only corrupt merchant. In a forensic study conducted on trade through the port of Bristol in the mid-sixteenth-century Evan Jones (2001) has argued that: 1) not all merchants were smugglers; 2) those that were being dishonest were only doing so on certain goods (the export of leather, grain, and lead, for example, where particularly high profits were to be made); 3) the value of the smuggled goods was likely to far exceed the value of the declared goods and would account for a large proportion of the merchant’s profits. In one shipment of wheat in Bristol, for example, duty had only been paid on 100 quarters (one quarter was 28 lbs) whereas 504 quarters were exported.

Regardless of the precise figures, Shaxton’s wealth certainly grew. (Interestingly the stipend for being mayor increased in 1569 – Shaxton’s first tenure – from £20 per annum to £60.) Because of his smuggling he could soon afford to lease five tenements with adjoining houses, stables, orchards, and gardens in Damsgate (now Norfolk Street). He then acquired three more tenements in Damsgate and one in Spinner Lane (?Blackfriars Street?). He took over five tenements in Purfleet Street, one in Wingate (Queen Street), and one in Briggate (High Street). He also rented eighteen acres of pasture land in West Winch. By the time he took his biggest vessel, the flagship “Anne Francis”, he had a fleet of seven other ships.

Francis Shaxton: Careless Talk Costs Money

All was well until 1573 when Downes started to get complacent and was careless. He tried to persuade James Mylles (a merchant from Rye with a grudge against the port of Lynn) to buy some illegal cockets. Mylles resisted and started to talk. Questions started to be asked. Downes was arrested and Shaxton visited him in prison. He offered to pay any fines in order to guarantee Downes’ silence. However, the prison experience was too much for Downes and he started to “sing like a canary”. Daniell felt he had nothing to lose and also talked. A Commission was set up to find out why the customs revenue from King’s Lynn was so meagre.

Shaxton was summoned to explain his part in the Downe’s affair. He admitted that occasionally his ships had gone off course due to the vagaries of the wind and that he had been forced to sell his perishable goods in foreign ports. Apparently, this had left him on the verge of bankruptcy. Shaxton admitted that he had used Downes’ cockets on five or six occasions and had loaded a few ships without the proper customs entry. He insisted that neither Sidney nor Ashwell were aware of what was happening, though Daniell was fully aware. He apologised for his “error’ of judgement.

An accusation that he had received 120 counterfeit cockets from Downes was dismissed as being too outlandish to be true. (Though it almost certainly was true.) Shaxton was fined a mere £523 which he was easily able to pay from his accumulated fortune.

Francis Shaxton: The Collective Shrug Of The Shoulder

To the modern reader it may seem surprising to learn that Shaxton was elected mayor for a second term in 1580. But his second term as mayor is indicative of the fact that at the time tax avoidance was considered an “understandable” pastime that many people took part in, including many at the upper echelons of society. Rates were high following a review under Queen Mary; the duty was going to London; and there was an inbred dislike of paying duty. As Cardinal Wolsey said in 1524, if people do not accept the justice of a tax, they will not pay it.

Although perhaps strange to the modern reader, his second election as mayor would probably have been unremarkable at the time. In 1555 two senior town merchants, Thomas Waters and William Overend were convicted of piracy. Their fines were paid by the Council of Lynn and they were sent to London as the town’s two MP’s. King’s Lynn’s Hall Books record: “Mr Mayor Aldermen and Common Council with one assent have condescended and agreed to allow and bear with Mr Waters and Mr Overend the sum of £160 towards the payment of a fine of late paid to the Queen’s Majesty and for their charges and expenses in that behalf”. In 1565 Sir Thomas Woodhouse was caught shipping grain overseas strictly against the embargo that he was empowered to enforce. He was not censured and continued as Vice Admiral until his death in 1572.

Shaxton’s return as mayor may also have been due to the fact that he knew too much about his voting peers for them to risk opposing his second term in office.

And it didn’t end there as Shaxton just couldn’t stop himself. If you knew how to do it, tax fraud was too lucrative to completely walk away from.

Francis Shaxton’s Tax Fraud: Part Two – The Wind Just Blew It Off Course

The removal of Downes and cockets from the scene had little effect on Shaxton’s business. It continued dishonestly much as before (with a few adjustments).

Businesses had to put up bonds for each shipment. If the ship went to another port and sold its cargo, the bond was forfeit. However, there was a loophole. The ship owner could argue that the ship was forced off course to another port by tides and weather, and was forced to delay because of repairs, and was then forced to sell perishable goods in order to avoid a heavy loss. And it was worth risking your £100 bond if you could sell your goods overseas for a £500 profit.

There were many Lynn merchants willing to engage in “creative” practices with Shaxton. One such was Bartholomew Wormell. The two men were engaged in several speculative ventures where their ships strayed into foreign waters in the hope on finding new customers and large profits.

On one such venture they loaded Shaxton’s “Mary James” with rye and malt and declared it was for discharge in Newcastle. It ended up in Dieppe where its cargo was sold. (The winds outside the Wash must have been really bad!) On return to England its bond was forfeited, but Shaxton petitioned for and obtained the return of the money. Similarly the “Antelope” was loaded with wheat and barley and declared for Shoreham. The cargo ended up being sold in Le Havre. Again the bond was forfeited, and again it was returned.

Francis Shaxton’s Marmalade in Wales

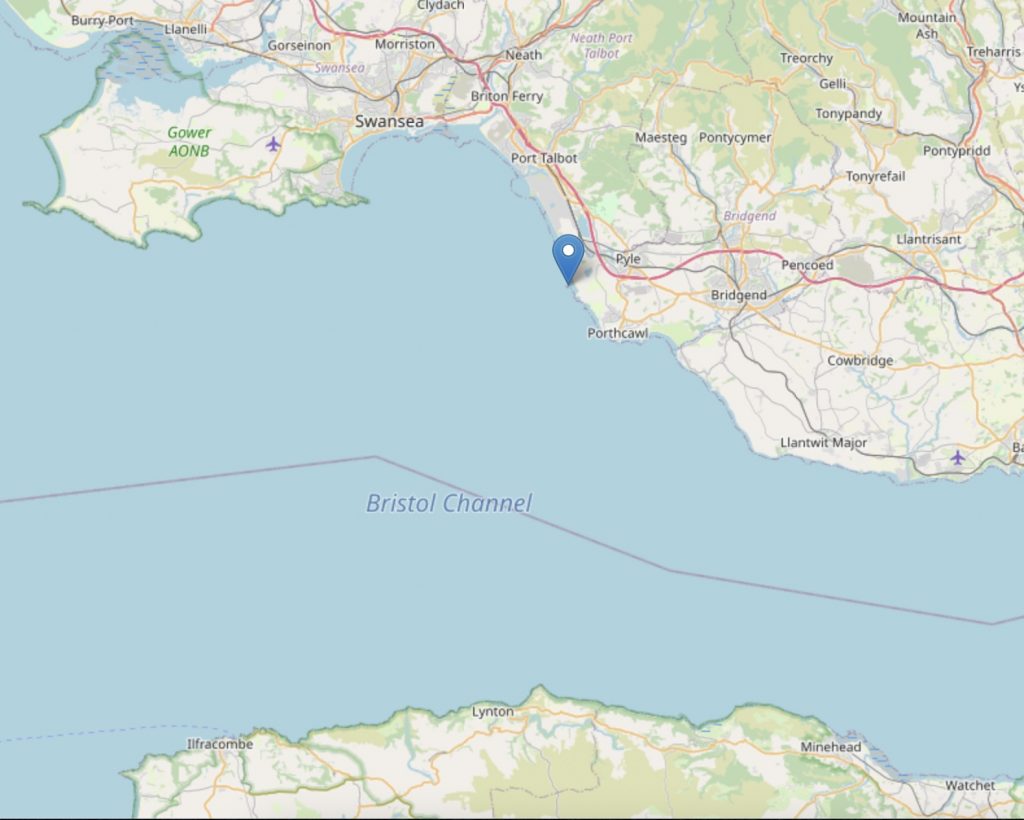

Today, if you walk along the beach at Margam in Glamorgan (above Porthcawl) in South Wales you might join the those who are lucky enough to find evidence of Shaxton’s dishonesty and pick up the odd old coin. Apparently a very few people still do.

In 1583 there was a shortage of grain in Europe and to ease the situation in the UK the government removed all export taxation on shipments of grain intended only for the domestic markets. This helped keep the price of grain down. However, the shortage meant that foreign European buyers were willing to pay a high price. It was a perfect scenario for a dishonest merchant.

Perhaps the flagship’s captain wasn’t very good at navigating as the “Anne Francis”, predictably, ended up in Cadiz. (It was meant to be going to Hartlepool.) Rather than return the ship full of grain the captain kindly agreed to sell the cargo to the Spanish who clearly wanted it and who were willing to pay a high price for it. (Shaxton bought it for £4 3s. a ton and sold it for £8 a ton.) When she left Cadiz the “Anne Francis” was laden with a cargo of out-of-date silver coinage worth £40,000 which would soon be melted down once back in England. The ship’s list also records a silver whistle and two cases of marmalade on board.

Perhaps the captain’s navigational skills really were inept, or the winds were really strong (or both). For whatever reason, on the return trip, instead of turning sharp right at Cornwall and going up the English Channel, the ship turned right into the Bristol Channel and the notorious Glamorgan wrecking coast.

In a storm and confusion the Anne Francis was wrecked off the beach at Margam in South Wales on 28 December, 1583. The Lougher family at the Skier Farm had watched the stricken vessel. They realised what was about to happen, prepared carts to get what they could before the alarm was raised and the local Lords were mobilised.

Francis Shaxton: Afterwards

The King’s Lynn authorities should have been alarmed that a ship destined for Hartlepool ended up with Spanish bullion in South Wales. Instead they simply awarded Shaxton licences for another 1,000 quarters of grain.

However, this time Shaxton’s finances were badly damaged. The cost of the new ship and the loss of the payment for the “Anne Francis” cargo meant that his business empire faced a decline. He also faced another financial blow in 1585 when along with his partners Thomas Claybourne and Thomas Graves (who were operating from Marriott’s Warehouse) he lost the monopoly of the salt trade.

The next we know of Shaxton is a reference in the Council’s Minute Book for 21 August 1592 which removes Shaxton from his aldermanship as he hadn’t been in the town for seven years. There is no record of his death, or of his will and probate, which is strange for a man of his standing. We do know that the plague revisited the town during the 1590’s and killed his wife in 1596 and his daughter-in-law in 1600. It may be that he left to get away from the disease. He may have taken his remaining money and run off with another partner. It may be that at some point he was lost at sea on one of his ventures. It may be that he landed on another continent and decided to stay. We will never know.

Francis Shaxton may, or may not have been England’s greatest smuggler. He certainly wasn’t the only dishonest merchant in the country at the time. He may possibly have been the greatest crook ever to have held mayoral office in King’s Lynn – probably.

© James Rye 2022

See also Lynn Man Buys Alibi

See also Lynn Man Gets Away With Two Murders

Book a Walk with a Trained and Qualified King’s Lynn Guide

Sources

- King’s Lynn Hall Books

- Hipper, K. (2001) Smugglers All, Larks Press

- Jones, Evan T. (2001) Illicit Business: Accounting for Smuggling in Mid-Sixteenth-Century Bristol, The Economic History Review 54.1: 17–38

- Lewis, R. (2017) The Greatest Smuggler in England: The Life and Times of Francis Shaxton, Matador

- Williams, N.J. (1988) The Maritime Trade of East Anglian Ports, 1550-90 (Oxford Historical Monographs), Clarendon

Websites:

[…] customs officer is outwitted (or bribed). And Lynn had certainly had it’s smugglers such as Francis Shaxton who were well-off respectable members of the […]

[…] Lynn Mayor Cheats Customs For Years […]