A little knowledge can often be a dangerous thing. In telling stories historians can emphasise parts that seem important to them, or miss bits out that don’t quite fit the impression they want to create. In one sense, there is no such thing as a completely objective account, but some accounts are more careful in their consideration of the evidence than others.

As a child growing up in King’s Lynn I heard things about the town which I now know to be untrue. As a town guide I have heard and read things about the town which I also now know to be wrong. The account below is an attempt to challenge some of the falsehoods.

The Fictional Tunnel At The Red Mount

Photo © James Rye 2021

A couple of years ago I was acting as a steward at the Red Mount Chapel on Heritage Open Day. I was quite excited to be able to actually go inside the chapel and view some of the features I had learned about. Almost the first question I was asked by one of the early visitors was: “Where is the entrance to the tunnel?”

And I immediately understood where the questioner was coming from. As a child I too had picked up from somewhere that the chapel had a tunnel under the mount that joined it to Castle Rising. I can’t remember the putative purpose of the tunnel, though it may have had something to do with smuggling.

There are at least several problems with the tunnel theory. There is no physical evidence (documentary or archeological) that it ever existed .

And there are two other reasons why it couldn’t exist. First, the water table in the area is very high. The Walks are frequently flooded. There is a river behind the Mount. If any tunnel was built it would require considerable engineering to keep it dry which, even with today’s technology, would be near impossible. Second, the distances involved are too great. A tunnel of several miles would be too difficult to construct and maintain.

King John: The Completely Wrong King

I recently read in an otherwise interesting book that the town of Lynn, which was formerly known as Bishop’s Lynn, became known as King’s Lynn after King John gave it a charter in 1204. It’s an easy mistake to make. King John was important in the development of the town and gave it a charter in 1204. And despite being almost universally acclaimed as one of the most obnoxious of medieval kings (quite an achievement, considering there was quite a range to chose from), he is blithely celebrated in the town which saw fit to give him a commemorative statue.

However, despite the above, King John is the wrong king. King John’s charter still affirmed the rights of the Bishop of Norwich. It was the charter of 1537 from King Henry VIII that enabled the town to be called King’s Lynn. Up until that date it had still be Bishop’s Lynn. The town leaders had over 300 years of trying to work out what precise authority they had and what the Bishop of Norwich had. It was King Henry’s charter that freed Lynn from “the tyranny of the Bishop of Norwich”.

The Wash: The Apparently Insane Crossing

Although there are some writers who have interesting theories about what might have happened to King John’s treasure (see Waters, R. 2006 The Lost Treasures of King John: Second Edition), most mainstream historians believe what the Chroniclers stated – namely that King John left Lynn around 11/12 October, 1216, and that his treasure was lost in The Wash. But on the surface it seems a mad, almost impossible thing to do.

Until quite recently there were parts of this story that always puzzled me. The king’s party leaving Lynn would have been large. There would certainly have been the king’s chapel – not a quiet place of worship, but important religious artefacts and relics carried on a packhorse. He would have had a featherbed complete with linen sheets, rugs, and fur coverings, along with a portable urinal and bathtub. John’s wardrobe, containing strong chests with robes and valuable documents, travelled in long-carts, while his kitchen equipment was transported in other carts. A multitude of travelling officials attended to his domestic needs, including dignified servants like the Seneschal and Butler, as well as various lesser servants.

There may have been no monetary treasure in the baggage, but on the other hand, there may have been a considerable amount of money and jewels. During a time of civil-war it would not have been unreasonable for the king to carry considerable treasure with him. This would have been to prevent its theft if opposing forces got the upper hand, and/or it may have been used to pay mercenary troops as well as his own staff and soldiers.

If you were a king with lots of treasure, why would you risk your life and treasure over a risky crossing? And if you go to somewhere like Snettisham and look across The Wash, you inevitably have to ask why anyone would be so foolish to leave the shore.

In recent years I have come to learn that the crossing was less foolish than I had previously thought. First, John and his entourage left Lynn and made the journey to Swineshead Abbey via Wisbech (where he crossed the River Welland) and Holbeach and Spalding. His baggage train with all the carts and any treasure would have travelled much more slowly. In order to avoid getting too far behind, they decided to cross the estuary, cutting many miles off the detour route around Wisbech. But John himself never crossed the estuary.

It was not unusual for a king to be separated from his baggage while they were on the move. Heavy carts were slow, travelling at only two and a half miles per hour, and could be further delayed by poor road conditions and swollen rivers. Medieval communications suffered from a significant shortage of bridges. In contrast, the roads were suitable for well-mounted horsemen, allowing express messengers to travel 35-40 miles in a day. The king often moved his court 20-30 miles in a day, occasionally covering even greater distances.

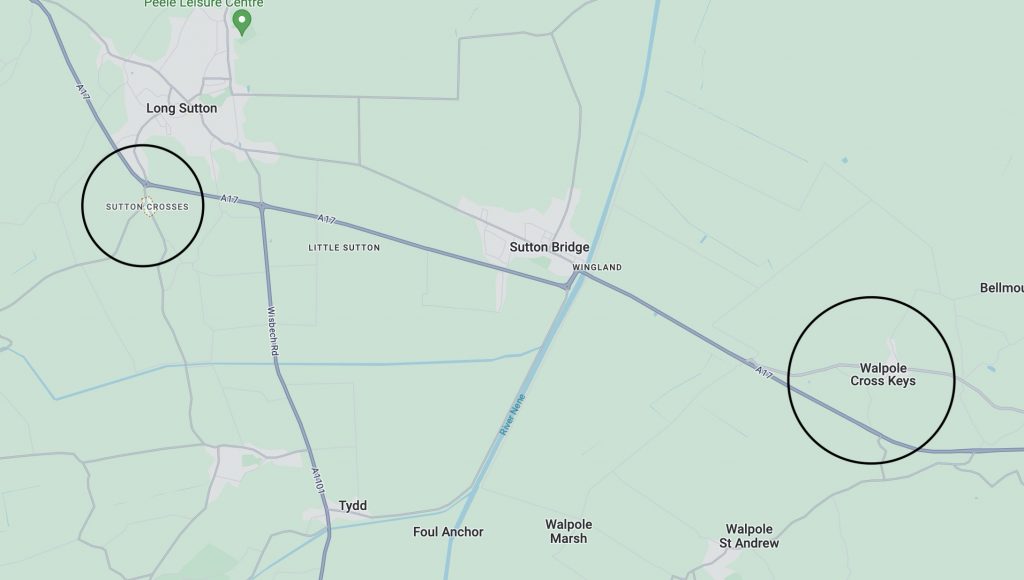

Second, there were was a well-established route across the estuary. But it wasn’t across the whole width of The Wash, just across a narrow part, from Walpole Cross Keys to Sutton Crosses (just south of Long Sutton). Rivulets of water would flow between saltmarsh flats which were only covered at high tide. A local guide could steer you across. The graveyard in St Mary’s Church in Long Sutton has a gravestone marking the burial of the last guide – a Charles Wrigglesworth, who died in 1840. The estuary land started to be reclaimed from 1640.

Clearly something went seriously wrong on this occasion in 1216. Perhaps they didn’t use a local guide. Perhaps they got the timings wrong. Perhaps one or more carts got stuck en route causing panic and delays. Whatever happened, the notion of crossing The Wash wasn’t as bizarre an idea as it may initially appear to a modern reader.

King John Cup: The Misnamed Treasure

Perhaps the most famous of the town’s treasures is the King John Cup. It is made of silver and has 31 panels of enamel attached to its body. All the figures on it are engaged in some form of hunting. These images confirm that it is not a piece of ecclesiastical plate, and, as such, is gives a very rare glimpse into the world of fine, secular silverwork. It would be easy to think that it belonged to King John and that it was retrieved from The Wash. Both suppositions are false.

The cup is completely misnamed as it has nothing to do with King John. It is thought that it was made in Flanders in the fourteenth century and was possibly made during the time of King Edward III. It may have been given to the town by one of Lynn’s rich medieval merchants. It is first listed in the town’s Hall Book in 1548, and is recorded as being used by the mayor for celebratory drinking in 1653.

Some might want to argue that its first appearance in 1548 is significant. The chantries and gilds were being dissolved in 1547 by Edward VI, with fixtures and fittings being sold or sent to London. Perhaps some of the Lynn worthies decided to save the cup and keep it in the town.

Trinity Guildhall: The Building That Wasn’t Destroyed

For many years local historians (and King’s Lynn Town Guides) have believed that the present stone building of the Trinity Guildhall, which majestically faces the Saturday Market Place, was not, in fact, the original building. The narrative has been that the original building was burned down in the great fire of 1421 (referenced by Margery Kempe in her Book) and that the present stone building was built after 1421 to replace it.

Photo © James Rye 2023

However, recent work by Susan Maddock has shown the above narrative to be untrue. I am indebted to Simon Bell (King’s Lynn Town Guide) for his clear summary of the facts:

- The main building known as the Trinity Guildhall was not severely damaged and rebuilt in 1421-23. The only damage was to the roof which didn’t prevent the building from being used.

- The building damaged beyond repair by the fire in 1421 was a timber-framed structure adjacent to the Guildhall owned by the guild and now the site of Stories of Lynn/Gaol House.

- The Trinity Guildhall dates from around 1300, albeit with various alterations.

- The building erected on the site of the fire in 1421-23 was demolished/rebuilt/remodelled to make way for the Gaol House built in 1784.

Thomas Thoresby: The Allegedly Wicked Farmer

One of my favourite buildings in the town is Thoresby College. The quadrangle was built in about 1508 to house a number of priests. It was built by Thomas Thoresby, a rich landowner in the area who made a lot of his money from sheep. He was known as a “flockmaster” and in his will he left his wife 100 ewes and his son 1000 wethers and 1000 ewes. He would have been involved in the lucrative export of wool to the low countries. After the temporary collapse of the market due, in part, to war, he would have have sold his wool to English cloth-makers.

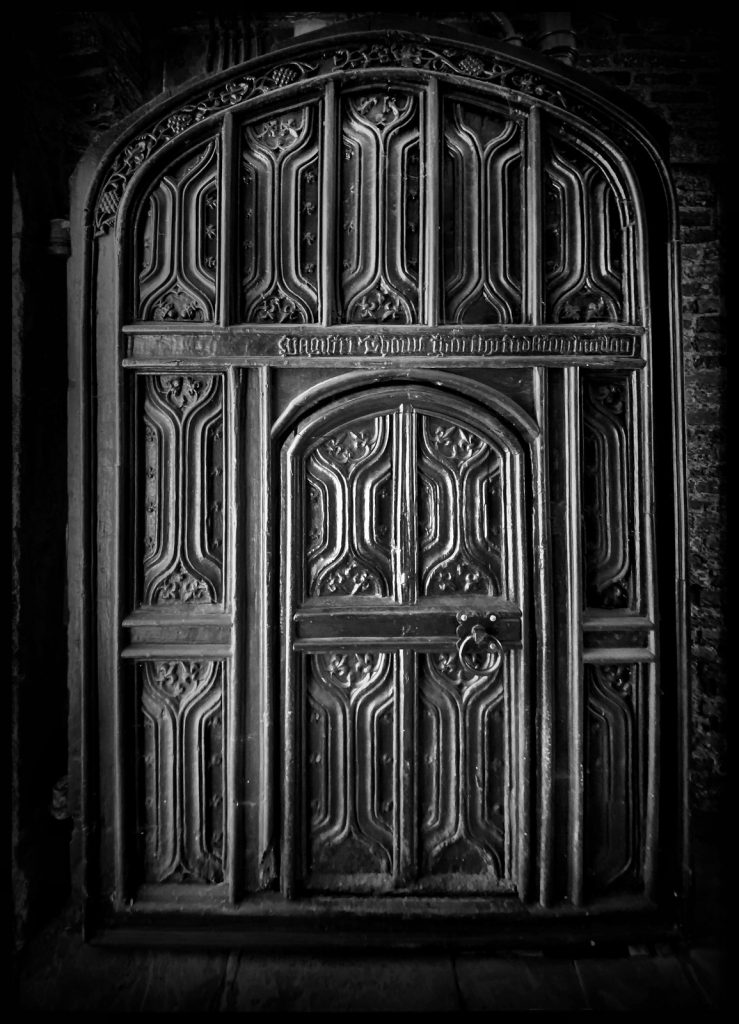

So why the accommodation for 16 priests? There is a Latin inscription (partially lost) above the small door through which the priests would enter. The original translates as, “Pray for the soul of Thomas Thoresby.” We know that in the Pre-Reformation days of 1508 people believed that one could shorten one’s time in purgatory (above hell, but below heaven), and hasten the soul’s progress to heaven, by having people still alive pray for you. The church taught that souls are drawn out of purgatory by prayers. So a superficial interpretation of the building (which I have actually heard argued) is that Thomas must have been a wicked man to need as many as 16 priests to pray for him to get him to heaven. Whatever did he get up to?

There are at least two things wrong with this reading of the building.

Photo © James Rye 2021

First, not all the priests were to pray for Thomas. Thirteen of them were to pray for the souls of the members of the Guild of the Holy and Undivided Trinity, which he was a member of. One priest was to pray for the people whose bones were in the Charnel Chapel and this priest was also to teach six boys grammar. Only the remaining two priests were to pray for the souls of Thomas and his family. Thomas was being far from selfish or wanting to expiate an unusually large mountain of sin.

Seondly Thomas was just doing what was normal for very rich people to do – namely pay other people to pray for them after death and set up institutions (Chantries) to enable it to happen. It was not unusual for vast sums of money to be spent after the death of a monarch, for example, so that hundreds, if not thousands of people would be paid to pray for the monarch’s soul. By 1547 when Edward VI closed down all the chantries (his father, Henry VIII had closed the monastries), the Reformation had moved on a pace, and praying for the dead had fallen out of theological favour. But in 1508, Thomas was just following custom and practice and using his wealth to attempt to invest in eternity. He was not the incredibly sinful farmer that some misguided people think he must have been.

Thoresby College: Not A School for Priests

People are easily confused by the word “college” and I’ve recently heard it argued that Thoresby College was a school for priests. Well, it wasn’t. It’s true that some learning did take place there – as argued above, one of the 16 priests who lived there was to teach six boys grammar. King’s Lynn Grammar School literally started in Thoresby College.

However, in the early sixteenth century the word had more of the meaning of “an organised body of persons engaged in a common pursuit or having common interests or duties; a body of clergy living together and supported by a foundation”. It was a college in the sense of 16 priests being bound together to do a job of work (pray for souls), living together, and supported by a financial foundation provided by Thomas Thoresby. The word “college” is clearly misleading for some in the twenty-first century.

Any education that took place in the building was primarily for the 6 boys, not the priests. (Although, of course, Latin was very useful if you wanted to be a priest, and that is where some of the boys may have ended up.)

© James Rye 2023

Sources

- Bell, S. (2023) Personal Correspondence

- Maddock, S. (1999) King’s Lynn Trinity Guildhall and Gaol, Leaflet produced by Norfolk Records Office

- Richards, P. (2023) Notes from a talk given on 600 Years of the Trinity Guildhall

- Robertson, B. (1996) Chasing the Shadows: Norfolk Mysteries Revisited, Elmstead Publications

- Waters, R. (2006) The Lost Treasure of King John: Second Edition, TUCANNbooks

- Warren, W.L. (1961) King John, Eyre & Spottiswoode

[…] The Wicked Farmer and Other Errors […]