Can you guess what you might find if you do a bit of digging into the history of King Street in King’s Lynn?

The Crossroads, The Oldest House, The Lost Lepers, and the Ambassador

The respectable present-day residents of King Street in King’s Lynn (now mainly solicitors, accountants, and restorers of Georgian townhouses) are a world away from their medieval counterparts. In the fourteenth century, King Street was known as Stockfish Row (latterly known as Checker Street). There would have been plenty of money around as the rich merchants were trading in one of the largest ports in medieval England. However, the street name gives away their trade. Many were importing and selling unsalted cod and herring which were preserved through drying.

Modern day visitors will admire the Georgian facades as they walk from the Tuesday Market Place to Henry Bell’s Custom House. However, most will remain ignorant of some of the street’s many fascinating secrets.

The Blocked Crossroads

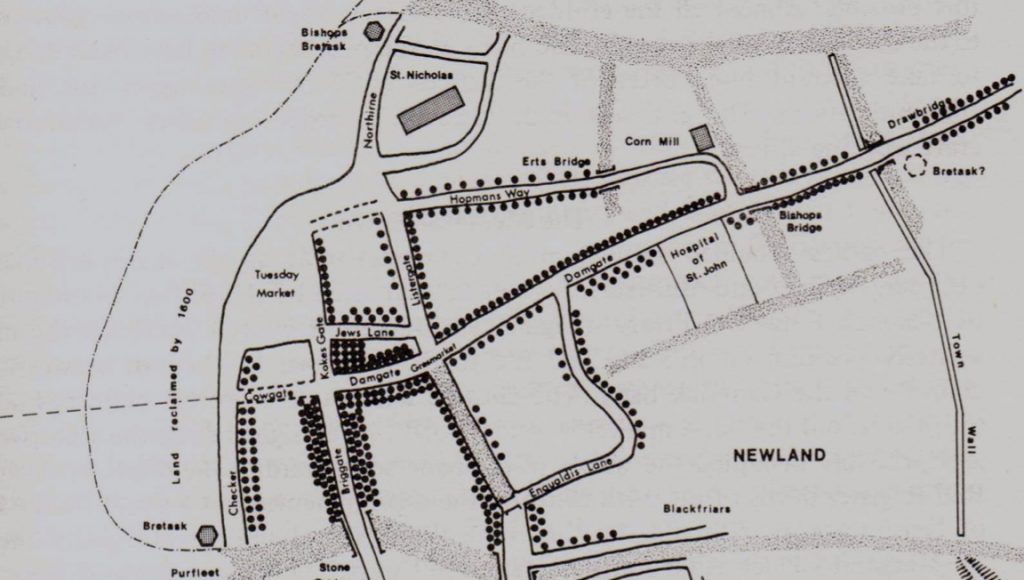

The current Ferry Lane is the only remaining visible clue to the existence of a former important route. From ancient times people have wanted to cross the river, and in the medieval period the ferry crossing provided access to, and from, routes through the Fens. In the early Middle Ages the Fenland district of Holland was one of the most prosperous agricultural areas in England. The route joins the ancient silt bank (one of the two east/west roads across the Fens) through Clenchwarton to Spalding , and through Lynn continues east towards two major north/south roads (Peddars Way and the Icknield Way).

As well as traders wanting to bring their goods to Lynn’s markets, this route would have been well used by the many pilgrims passing through the town on their way to, and from, the shrine at Walsingham. (During the Middle Ages Walsingham was the second most visited shrine in England – second only to the tomb of Thomas Becket in Canterbury. Every medieval king, including Henry VIII who finally closed the shrine, visited Walsingham.)

The direct route to Ferry Lane is obscured today by properties on the east side of King Street. People coming from Norfolk Street have to take the diversion via the Tuesday Market Place. In earlier times travellers coming through the town from Norwich would have walked up Damgate (now Norfolk Street). When they reached what is now High Street they would not have had to stop (as today), but could have carried straight on to Ferry Lane via a way called Cowgate.

Originally the Tuesday Market Place extended further down King Street, possibly as far as 32 King Street, with a path along the edge of no.32 known as Cowgate. Gradually areas to the North of Cowgate got built up and reduced the Tuesday Market Place, but the access way still remained.

Modern day shops have blocked an important medieval route.

The Hidden House

If you ask people which is the oldest house in King Street most people would point to the buildings nearly opposite Ferry Lane. Indeed, the buildings are very old. They are two storeyed timber framed buildings of the late 14th century which originally accommodated shops. However, inside exists a 12th century (c.1180) stone house (40 feet X 20 feet) complete with intact end gables, Romanesque arcading on both walls and a building line clearly defined and distinct from today’s building line.

Photo © James Rye 2021

It can claim to be the oldest surviving house in King’s Lynn. Nobody knows who originally lived there, but there are several theories attempting to answer some questions. We know that whoever it was must have been rich, because stone houses were expensive to build (and rare in this period).

The Tuesday Market Place may have extended down to Cowgate, and one possibility is that it was a merchant with a shop overlooking the new market square. The stone would have provided security for products and takings.

Another possibility is that it was owned by the ferryman. The location makes sense, and he would have been an important person for the community.

The Lost Lepers

The first hospitals for lepers (leprosaria) or Lazar Houses appeared in the eleventh century. Such houses were built on the outskirts of towns as isolation blocks. However, they were also often near main roads as the lepers needed to beg for alms – often agreeing to pray for the donor in return.

In his will of 1432, Stephen Guybon donated 12d to every house of lepers in the Lynn area. The houses were at West Lynn, North Runcton, Setchey, Gaywood, and Cowgate. The last two places are interesting. Not many people who pass by the present KES school on Gaywood Road know that the Mary Magdalen Alms Houses next door to it was originally a Lazar House. However, the reference to Cowgate is really interesting.

All the other Lazar Houses in that list are outside the town wall. The vast majority of other known Lazar Houses in the country are away from close domestic or commercial contact. So why did Lynn have one in Cowgate, close to the stone house mentioned above, inside the town wall?

There are two possibilities, very tentatively offered (and both may be wrong). One is that the Lazar House in Cowgate existed by a travel route from the early twelfth century as the town was growing (perhaps even before the town came into existence). Remember that the early part of Lynn grew around the Saturday Market Place, not the Tuesday Market Place. As the town grew the Lazar House could have been accommodated rather than destroyed.

A second possibility is that it could relate to the ferry. Whether or not the ferryman lived in the stone house (see above) he would definitely have lived nearby. One hypothesis is that amongst the large numbers of pilgrim travellers using the crossing, there would have been a number of lepers making the journey. Assuming that most of the healthy travellers would not have wanted to be in close proximity to, or in the same boat as the lepers, a leprous ferryman would be needed to take contingents of fellow sufferers across the Great Ouse.

The Forgotten Ambassador

Next door to Ferry Lane is the Old School Court. It was on this site (not this more modern building) that a Lynn man grew up to become what some historians have described as one of the most significant statesmen in the eighteenth century. What is sad is that very few Lynn people now have ever heard of him (perhaps because Anglo-Spanish diplomacy is not at the top of every local’s must-know list).

Photo © James Rye 2021

Benjamin Keene was born in 1697 and grew up on King Street. His father was a timber merchant, but very significantly his maternal grandfather, Edmund Rolfe, was Robert Walpole’s election agent. Keene went to the local Grammar School, and then on to the universities of Cambridge and Leiden where he studied law. When Sir Robert Walpole was looking for men to become his eyes and ears throughout the continent, Keene was an obvious choice.

By 1724 Keene was working as a British Consul in Spain, and eventually he went on to be, at separate times, both Ambassador to Spain and Portugal. Between 1728 and 1757 he worked for his country negotiating commercial and peace treaties with Spain, France, Austria, and Sardinia, with most of his time spent trying to prevent war between Britain and Spain.

Ironically, his greatest achievement is what didn’t happen. In 1757 Britain entered the real First World War (fighting in what was to become Canada, in the Americas, in the Caribbean, in Cuba, in Europe, in India, and in the Philippines). Keene used his knowledge of the Spanish Court and his friendship with the king, Ferdinand VI, the keep Spain out of the war for six of the seven years.

His funeral urn, paid for by public subscription, is in St Nicholas Chapel, King’s Lynn.

Read more about Sir Benjamin Keene.

© James Rye 2021

Book a Walk with a Trained and Qualified King’s Lynn Guide

Sources

Parker, V. (1971), The Making of King’s Lynn: Secular Buildings from the 11th to the 17th Century, Phillimore

https://www.klprestrust.org.uk/project/king-street/

https://intriguing-history.com/medieval-leprosy/https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=1354228&resourceID=19191

https://elizabethashworth.com/2010/07/22/leprosy-in-the-middle-ages/

[…] Brandon, Swaffham, Castle Acre priory, and East Barsham. From the north, pilgrims crossed Fens via the ancient silt bank route and came through King’s Lynn (then called Bishop’s Lynn), before going Flitcham, Rudham and […]