Eugene Aram – possible philandery (sex), definite philology (words), plunder, murder, and the King’s Lynn Grammar School.

On 16 August, 1759, Eugene Aram, a former King’s Lynn Grammar School teacher, was hanged for the murder of his former friend some 14 years earlier. The teacher was executed in York. Because he was convicted of murder, as a deterrent to others, Aram’s body was gibbeted (hung in chains) in Knaresborough Forest.

Eugene Aram: Trouble in Knaresborough

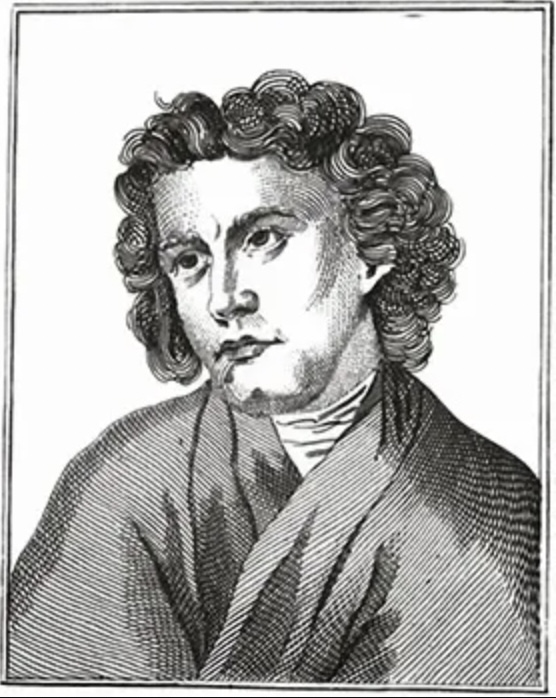

Eugene Aram was born in Ramsgill, Yorkshire in 1704. Although he came from a very poor background the boy initially obtained access to books via different employers. Over time, he managed to teach himself Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Chaldee, Arabic, and several Celtic languages. In later life he recognised truths that were not admitted by scholars for another hundred or so years – namely that Latin was not derived from Greek, and that the Celtic languages were related to other European languages. Unfortunately he is more remembered as a murderer rather than as an ground-breaking philologist.

While he was still young, Aram’s girlfriend became pregnant and he married her. He eventually settled as a schoolmaster at Netherdale. In 1734 he moved to Knaresborough, where he remained as schoolmaster till 1744.

Public Domain

In 1744 Aram became embroiled in a local scandal that eventually caused him to leave his wife and seven children in Knaresborough and move to London.

A close friend of Aram’s, a shoemaker called Daniel Clark, was thought to have come into a considerable amount of money from his wife. On the basis of this rumour, Clark purchased a variety of valuable goods on credit. Unfortunately Clark suddenly disappeared with the goods, and at the same time, Aram started to settle many of his own debts.

As one of his closest friends, Aram had been questioned about the activities of the swindling shoemaker, but could shed no light on Clark’s current whereabouts. The discovery of some of the missing goods in Aram’s garden may have been a little compromising, but Aram said that Clark himself had left them there. With no evidence to suggest otherwise, the official enquiries ended there.

Eugene Aram: Arrest in King’s Lynn

For several years Aram travelled through parts of England, teaching in a number of schools. In February 1758, the King’s Lynn Grammar School welcomed Aram as its new schoolmaster. The building was modest. The school was housed in a room above the Charnel Chapel on the Saturday Market Place adjacent to the church of St. Margaret’s. However, the new teacher came with very impressive qualifications, and by this time, he was he doubtless hoping that any hint of scandal had long been left behind.

Unfortunately in February 1758 a local workman in Knaresborough was digging for stone and discovered a whole skeleton. The local police remembered the strange disappearance of Daniel Clark and went to talk to Aram’s estranged wife. She had long since felt that her husband had something to do with Clark’s disappearance. She also gave the name of Richard Houseman as a possible accomplice. Mrs Aram now revealed that she found her husband burning clothes in the garden on the day after Clark’s disappearance.

When questioned by the police Houseman indicated he knew the skeleton was not Daniel Clark because he knew where Clark was in fact buried – in St Robert’s Cave, a well-known spot near Knaresborough. Houseman also said that Aram had killed the shoemaker.

A horse trader recognised Aram in Lynn and reported his location back to Yorkshire. Two constables, John Barker and Francis Moore, were dispatched to King’s Lynn. When approached by the constables Aram panicked and denied that he had ever known Clark. He was arrested on the spot on 21 August 1758.

Eugene Aram: The Trial And Defence In York

Aram had plenty to say in his defence. Prior to his trial on his journey north he had protested his innocence. He now admitted that he really had known known Daniel Clark, but he said that had no connection with the shoemaker’s fraudulent activity. He said that he had no idea what had happened to Clark and that it wasn’t true that he’d tried to get a number of people to say that they had ideas about where Clark might have gone to.

His three-day trail began on 3 August 1759 at York County Court. Aram chose to defend himself through a prepared statement. He did not try to overthrow Houseman’s evidence, but argued:

- A man of his education and academic standing would not be involved in murder.

- He lacked motive, being more interested in study than in wealth.

- He disputed that Clark was even dead. He gave several examples of people who had disappeared before in suspicious circumstances – only to reappear alive and well many years later.

- There were loads of skeletons in the ground. Knaresborough was once home to a military garrison – there were probably skeletons all over the place.

- Trying to identify a victim from a skeleton, he said, was an attempt to “determine what was indeterminable.” He gave examples of other ‘suspicious’ skeletons that had recently been dug up but which had been in the ground for a number of years. Aram pointed out that a skeleton unearthed at Woburn Abbey in 1744 still had some flesh on the bones that showed evidence of knife cuts – but it had been underground for at least 200 years. He also tried to show that the bones found at St Robert’s Cave were probably those of some hermit who had taken up his abode there. He correctly pointed out that they had misidentified the first skeleton found, so the second body might equally be anybody.

The argument about the uncertainty of the identity of the skeleton may seem valid. And, of course, a modern reader would require more forensic evidence. However, the jury were not convinced by the academic, and Aram was found guilty and condemned. The jury came to their conclusion without even having to leave the courtroom.

Eugene Aram: Afterwards

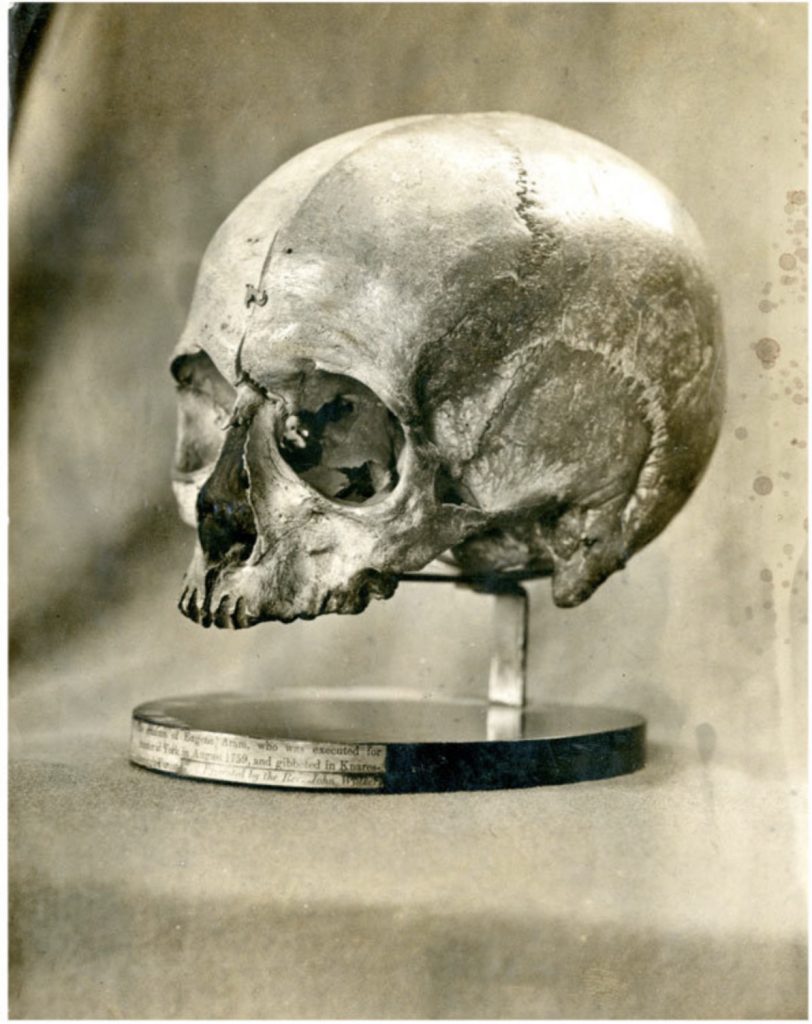

King’s Lynn Museums

While in his cell awaiting death Aram confessed to the murder and threw light on his motive – he said he had good reason to suspect an affair between Clark and his wife. It was a crime of passion that he deeply regretted. On the day before his execution he had unsuccessfully tried to kill himself by opening his veins with a razor.

Eugene Aram was hanged in York at Tyburn Prison on 16th August 1759, and his body was hung in chains (gibbeted) in Knaresborough Forest. His skull was acquired in the 1830s by a man called Hutchinson, a local doctor. It passed through several hands before eventually being returned to King’s Lynn in 1993, when it was gifted to the town by the Royal College of Surgeons. It now sits in the Stories of Lynn Exhibition near the site where Aram briefly taught.

The murderer is celebrated by Thomas Hood in his ballad The Dream of Eugene Aram, and by Edward Bulwer-Lytton in his 1832 novel Eugene Aram.

© James Rye 2022

Book a Walk with a Trained and Qualified King’s Lynn Guide Through Historic Lynn

Sources

- Tarlow, S. (2017) The Afterlife of the Gibbet. In: The Golden and Ghoulish Age of the Gibbet in Britain. Palgrave Historical Studies in the Criminal Corpse and its Afterlife. Palgrave Macmillan https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-60089-9_3

- Tarlow, S., Battell Lowman, E. (2018). Hanging in Chains. In: Harnessing the Power of the Criminal Corpse. Palgrave Historical Studies in the Criminal Corpse and its Afterlife. Palgrave Macmillan https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77908-9_6

- https://allthatsinteresting.com/gibbet

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Eugene-Aram-English-scholar

- http://www.britishexecutions.co.uk/execution-content.php?key=2140

- https://www.geriwalton.com/eugene-aram/

- https://www.klmagazine.co.uk/articles/eugenearam

- https://murderpedia.org/male.A/a/aram-eugene.htm

- https://norfolkrecordofficeblog.org/2019/03/12/a-murderer-in-the-school-the-case-of-eugene-aram-of-kings-lynn/

- https://oldlennensians.co.uk/history/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eugene_Aram

[…] Original Article […]

[…] Aram (1758): Eugene Aram was a talented linguist who took up his post as a teacher at King’s Lynn Grammar School in […]