How the River Great Ouse Found Lynn – and Left Wisbech Behind

During the Middle Ages, King’s Lynn became one of England’s busiest and most prosperous ports. To its contemporaries, Lynn was what Liverpool would later become during the Industrial Revolution: a powerhouse of trade, linking inland England to the wider world. Yet this success was not inevitable. Had a river taken a different path, the story of Lynn might have been very different.

The Great Ouse: A River with a Restless Course

The River Great Ouse, the longest of the Fenland rivers, rises near the Cotswolds and winds more than 150 miles to the Wash. Today it meets the sea at Lynn, but this has not always been its route. Over thousands of years, floods, silt, and human intervention have repeatedly changed its course.

Photo © James Rye 2020

In early medieval times, the Ouse flowed north-east from Huntingdon and Ely through the Fens to Wisbech, where it joined the River Nene and entered the Wash. Wisbech, sitting on this tidal estuary, became a natural port. By contrast, Lynn, then little more than a riverside settlement (fed by the Nar, the Gaywood River, and possibly another river called the River Lin). But it had no direct access to the main river system.

Floods, Silt, and Human Ingenuity

By the thirteenth century, the old Wisbech estuary had become treacherous. The slow, meandering channels of the lower Ouse filled with silt, choking navigation and worsening floods across the Fens. Local landowners and monasteries were desperate for relief.

Among them was the Bishop of Ely, one of the most powerful figures in eastern England. His estates at Littleport and Ely suffered chronic flooding, and his tenants struggled to drain the land. Elsewhere, the Abbeys of Ramsey and Crowland faced similar problems. Around this time, an old Roman drainage ditch near Littleport was reopened by the Bishop of Lichfield and Coventry to carry away floodwater, and a dam was constructed to control it. These works, though local in intent, began to redirect water into channels that would eventually lead to Lynn.

The Great Break at Denver

Nature then lent a dramatic hand. Early in the thirteenth century, a massive flood burst through a natural ridge near Denver, a few miles inland from Lynn. The breach allowed the Great Ouse to spill northwards, cutting a more direct course to the Wash.

Recognising an opportunity, the Crown sanctioned further engineering. In 1236, under Henry III, royal approval was granted “to make a channel to the sea towards Lynn.” The work was likely organised jointly by the Bishop of Ely and local monastic landlords, with strong support from the ambitious burgesses of Lynn, whose newly chartered borough (since 1204) depended on waterborne trade.

This was not a single dramatic diversion but a series of interventions over many years. Channels were cut, embankments built, and floods gradually coaxed into the new course. By the later thirteenth century, the main stream of the Great Ouse flowed decisively to Bishop’s Lynn rather than Wisbech.

By the 1470’s the transition was largely complete. The River Nene was also diverted to join the Great Ouse’s new course, further cementing Lynn’s status and leaving the old Wisbech channel to silt up.

Building the Town into the River Great Ouse

Photo © James Rye 2023

The new waterway transformed Lynn. The townspeople didn’t merely adapt to it – they built into it. Over time, wharfs and jetties extended the riverfront westward, trapping silt and turning mudflats into firm ground. Houses were built over cellars that served as warehouses, and private merchants established quays in front of their properties. The Ouse and the town became inseparable: a working landscape shaped by trade, labour, and tide.

Winners and Losers

For Wisbech, the change was ruinous. Its once-broad estuary narrowed and silted until large vessels could no longer reach it. The town’s maritime trade declined sharply.

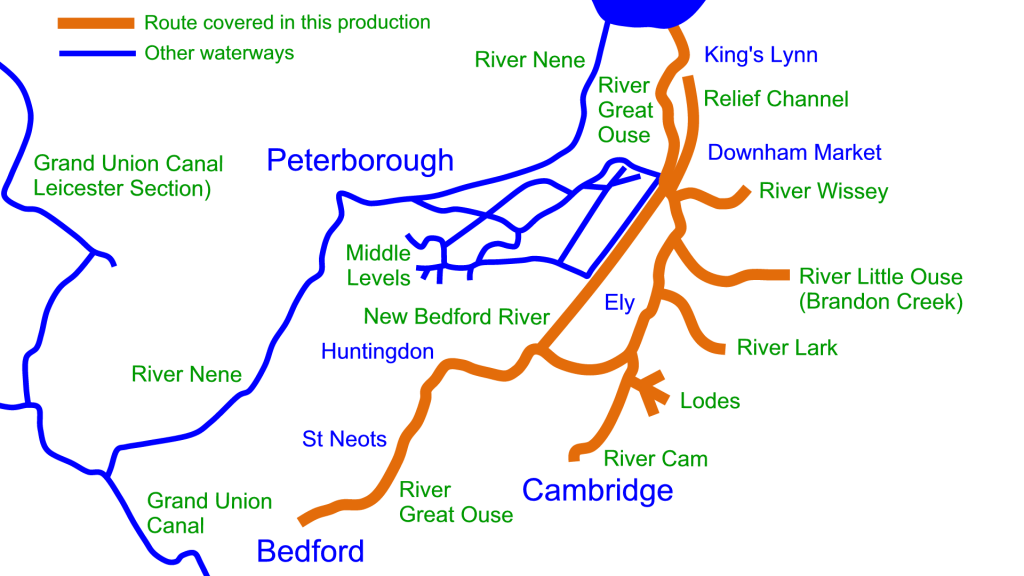

Lynn, by contrast, was transformed into a port of national importance. Its access to the inland waterways gave it connections with Bedford, Huntingdon, Ely, Cambridge, Northampton, Peterborough, and Bury St Edmunds. Wool from the eastern counties was brought downriver for export, while imported wine, wax, salt, coal, and timber were distributed inland.

Lynn’s position on the East Coast also made it ideal for trade with Flanders, the Baltic, and Scandinavia. Its merchants established links with the Hanseatic League, and by the fourteenth century the town’s riverfront bustled with warehouses, cranes, and foreign ships. Pilgrims, too, arrived in their thousands, travelling to the famous shrine at Walsingham. Many visited the Red Mount Chapel or hired boats to sail up the River Nar to Castle Acre, shortening their onward journey on foot.

The River Great Ouse: An Engine of Medieval Prosperity

By the end of the thirteenth century, Lynn had become the chief port of the Great Ouse system, handling the trade of seven counties. Royal customs records, wharfage dues, and merchant accounts all attest to its wealth. It was, quite literally, the Warehouse of the Wash – the place where England’s inland produce met the seaborne world.

Yet its prosperity rested on a delicate foundation. The Ouse’s new course required constant maintenance. Floods, silting, and political quarrels between landlords and local corporations forced repeated dredging and embankment work. Later, in the seventeenth century, the Bedford Level drainage schemes straightened and deepened the river once again, securing the route that remains in place today.

The Accident that Made a Port

Looking back, it is striking how much depended on a combination of necessity, foresight, and chance. Without the flood at Denver and the decision of 1236 to direct the river “towards Lynn,” the Ouse might have remained loyal to Wisbech. Lynn could have stayed a minor coastal village, while Wisbech might have grown into the leading port of the Wash.

Instead, the diverted river made Lynn the natural outlet for half of eastern England. Its merchants, churchmen, and builders seized the opportunity, turning an accident of geography into the foundation of one of medieval England’s most prosperous towns.

At Lynn The Changes Continue

Later modifications, such as the Eau Brink Cut (completed in 1821), straightened the lower river near King’s Lynn for better drainage and navigation, but it did not alter the well-established outfall into the Wash at Lynn.

A new, more straightforward outlet for the river into the Wash was finished in 1853 by the Norfolk Estuary Company. This major project diverted the Great Ouse away from the awkward, shallow loop that curved round King’s Lynn and its old tidal approach. It gave the port a deeper, more reliable channel running across the reclaimed land north of the town.

After serious flooding in 1937 and again in 1947, a major flood protection plan for the Great Ouse was finally approved in 1949. Costing £10.5 million, it involved building a relief channel that runs alongside the main river from Denver to Saddlebow, near South Lynn. Later, in 1964, a new waterway was completed to carry the upper reaches of the Wissey, Lark, and Little Ouse into the Great Ouse close to Denver Sluice.

© James Rye 2025

See also: A Lot of Digging – Eau Brink Cut

Further Reading

- Bettey, J. H., “The Great Ouse and the Development of the Port of King’s Lynn,” The Geographical Journal 144 (1978): 54–66.

- Darby, H. C., The Draining of the Fens: A Study in Historical Geography. Cambridge University Press, 1956.

- Miller, Edward, The Abbey and Bishopric of Ely. Cambridge University Press, 1951.

- Ravensdale, J. & Muir, R., East Anglian Landscapes: Past and Present. Michael Joseph, 1988.

- Saunders, K., Three Million Wheelbarrows: The Story of the Eau Brink Cut. Mousehold, 2021.

- Victoria County History: Cambridgeshire and the Isle of Ely, Vol. 4. Oxford University Press, 1953.

- Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/River_Great_Ouse

[…] The importance of the river to the town should not be underestimated. See here. […]

[…] George Vancouver was born in the thriving Georgian port of King’s Lynn on June 22nd in 1757. George’s father, John, was a deputy collector at the Custom House. George grew up in a town dominated by shipping traffic. Along the coast vessels between Lynn and Newcastle carried corn and coal, and from further afield, coal, wine, and timber were imported in large quantities and distributed through the river system to seven counties. […]

[…] town’s position on the east coast enabled it to benefit from the trade with the continent. The River Great Ouse gave the port a large hinterland for distributing and collecting goods (10 counties), so the import […]

[…] it always hadn’t done so (see HERE), by 1821 the River Great Ouse had flowed into the Wash at King’s Lynn for several centuries. […]