There were so many people willing to commit perjury in support of Franklyn that the trial took seven hours.

Thomas Franklyn – King’s Lynn Smuggler

Introduction

It is easy for us to have a romantic notion about smuggling – particularly smuggling that took place a long time ago (when nobody we personally know is getting hurt or defrauded). And King’s Lynn had certainly had it’s smugglers such as Francis Shaxton who were well-off respectable members of the community.

There are tales of swashbuckling heroes helping people earn extra cash and get cheap goods. Barrels of spirit and oil-skinned sacks of tobacco disappear through the sand dunes to be stored in barns and church towers and lofts before being distributed along the networks. All the while the foolish and impotent customs officer is outwitted (or bribed).

But smugglers weren’t romantic do-gooders interested in levelling up the poorest in society. They were often violent men (such as Thomas Franklyn and William Kemball) who wanted to make and protect their own fortunes. The smugglers may have been briefly admired, but few people would have doubted that they were in the smugglers’ debt and that quick justice would be meted out if they fell out of line. And people who tried to stop the illicit trade often paid with their lives. A Government Commission for 1736 found that in the previous decade over 250 Customs and Excise Officers had been injured, with six of them being murdered.

Thomas Franklyn

Thomas Franklyn was one of Lynn’s more notorious smugglers.

He was born into poverty and squalor in King’s Lynn’s North End. He initially worked as a labourer in a warehouse where animal skins from America and the Arctic were traded. He started taking small quantities of smuggled tea to households, and before long had an extensive distribution network under his control. At the peak of his career in the 1780s he employed hundreds of people recruited from the many villages of North Norfolk.

He would have employed:

- sailors who brought the ships from the Continent and rowed the merchandise ashore;

- lookout signallers who watched the coast for any signs of officialdom;

- carriers who transported the goods into hiding;

- civilians who were bribed to allow their storage spaces to be used;

- transporters who moved the goods along communication arteries such as Peddars Way;

- “batmen” who used clubs to protect the convoys moving along tracks and roads to their ultimate destination;

- numerate cashmen who could count and keep records.

In the villages of North Norfolk most people would have been “touched” by smuggling in some way.

Franklyn is described as having an intimidating physical presence. With this physical presence and the knowledge that he commanded hundreds of people, he tended to think of himself as untouchable.

In 1779 Franklyn came up against his sturdiest foe to date. Robert Bliss was the new Excise Officer who had arrived at Wells with responsibility for the beaches from Old Hunstanton to Stiffkey. Bliss was resolute that he would not be bribed but that he would supplement his income by legitimate means – he would take his just share of any captured smuggled goods.

Thomas Franklyn: Intimidation and Failure

Soon after his arrival at Wells Bliss received this anonymous letter:

Bliss. As you have begun to plunder and deprive us of our property, we will now begin with you and for your followers for your blood. We are determined to have you or any that belong to you, by night or by day, sooner or later you plundering rascal. We can have 200 men to join us any day we please. As such we can bid you defiance and determined we are to have at you, for by God we will have our lives. These from “Free Englishmen”

There was no doubt that the ultimate source was Franklyn but Bliss was not intimidated by it.

For the next two years two things happened. First, Bliss continued his quest to stop Franklyn. Franklyn was arrested and successfully convicted on three occasions for beating up Bliss’s Excise Officers. On all three occasions he was fined 1s. There was no local appetite for making an example of him.

The second thing that happened was that Bliss was successful in having a serious impact on Franklyn’s trade. Although Bliss couldn’t raise enough troops to successfully intervene and catch the smugglers red-handed, he could use informers. Bliss adopted the tactic of finding and confiscating the hidden goods after they had been taken from the beach. For example, in February 1780 Bliss seized 1,000 gallons of gin, 400 lbs of tea, and 260 lbs of camphire off Hunstanton. In November Bliss seized 500 gallons of brandy and 9 bags of tea. The recaptured goods were legitimately divided between the government and the captors. It is said that Bliss increased his salary ten-fold during these years.

Thomas Franklyn: The Christmas Humiliation

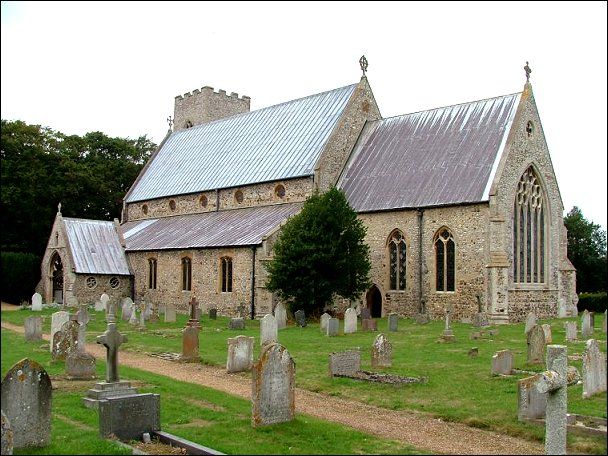

In December 1782 Bliss gained intelligence that a large amount of brandy, gin, and tea had been landed on 22nd and was being stored in the St Mary’s Church Tower in Old Hunstanton. Bliss decided to humiliate Franklyn by raiding the church during the Christmas Eve service. He knew that several important gentry would be present including a Grand Jury member from the County Assizes, at least two Justices of the Peace, as well as the Le Strange family and several of Franklyn’s supporters. He knew Franklyn’s supporters would not dare oppose him in front of such an audience.

Bliss arrived at the church with a party of dragoons, surrounded the building, and then entered during the service. The congregation watched as a seemingly inexhaustible supply of barrels and of oil-skin bags were passed from dragoon to dragoon and then to wagons outside the church.

Frankly was present but was powerless to move. But he knew that he had to move in order to regain his reputation. And in the very early hours of 1 January 1783 he took his revenge.

Thomas Franklyn: The Revenge

Bliss was lured into a trap. He was told that there were shipments of smuggled goods in particular houses in Thornham. Bliss arrived in the middle of the night with a small party of six dragoons at the first house. He discovered the smuggled goods, but the occupier seemed genuinely innocent, confused, and afraid.

We don’t know if Bliss suspected something was wrong, but regardless, he decided to move to the next house on the other end of the village. It was his big mistake. He and his party soon found themselves surrounded by hundreds of men armed with firearms, pokers, and forks, and their entry and exit blocked. Franklyn appeared and mocked the small party and threatened to murder them all. He grabbed the reins of Bliss’s horse, pulled him close and then bludgeoned the Exciseman several times on the side of his face. The end of a lead-loaded whip bit deeply into his eye-socket.

Sergeant Boutell of the 11th Dragoons intervened to prevent a certain massacre. He withdrew his sabre with its thirty-seven inch blade, took hold of the reins of Bliss’s horse, and charged directly through the enemy. Encouraged by the sergeant’s actions, the rest of the cavalry followed in swift pursuit. Several people were wounded by sabre slashes.

The village of Thornham suffered for several months as the government sent troops and press-gangs to suppress any rebellion. Able-bodied men hid or temporarily moved elsewhere. The regular income from smuggling immediately stopped. Franklyn hid in Lynn in the North End.

Thomas Franklyn: The Wedding Capture

On 6 January 1783, while several of his men were being arrested in Thornham, Franklyn was getting drunk in the alehouses of Dowshill Street (Pilot Street) and Hogman’s Lane (Austin Street) celebrating a wedding of one of his henchmen. A peace officer who had been charged with arresting Franklyn recruited three press gang members and made a first attempt. Franklyn kicked and screamed, and within seconds a mob of around 20 appeared and the arresting four withdrew.

A second attempt to capture one of Franklyn’s associates also failed. After a brief meeting at the Black Goose pub on Woolmarket (St Nicholas Street) the arresting party felt that they had no alternative but to call the West Norfolk Militia. At 10 o’clock in the evening the arresting party with 14 foot soldiers arrived at Franklyn’s house in a cul-de-sac off Hogman’s Lane where the wedding celebrations were continuing.

When the arresting party opened the house door Franklyn discharged a blunderbuss. Thankfully the two arrestors immediately fell to the floor and were not hurt. However, the militia colonel heard gunfire and immediately ordered his soldiers to fire their muskets. Lead balls smashed through windows and doors into the house. A tailor was shot through the heart and died instantly. A woman was shot in the arm which later had to be amputated. Franklyn was captured as he tried to escape over a roof.

Thomas Franklyn: The Escape

Franklyn was briefly held in Lynn before being sent to the County Gaol in Norwich Castle to await trial in the County Assizes at Thetford in March. In theory he was facing a death sentence, but he had time to brief a solicitor and set in motion the buying of witnesses.

On 14 March 1783 there were so many people willing to commit perjury in support of Franklyn that the trial took seven hours. Crucially Bliss was in no state to attend or give evidence, but a seemingly endless procession of witnesses testified that Franklyn was not in Thornham on 31 December/ 1 January. The Prosecution case was overwhelmed by perjured evidence. The jury provided a unanimous verdict of not guilty.

Franklyn retained his fighting spirit, but given how Thornham had suffered after the incident, people were less keen to trust him. His heyday was over.

Bliss lost the sight of his eye and suffered what today might be classed as post-traumatic stress syndrome. He was unsympathetically dismissed from his post without a pension in 1787.

© James Rye 2022

See also Lynn Mayor Cheats Customs For Years

See also Lynn Man Gets Away With Two Murders

Book a Walk with a Trained and Qualified King’s Lynn Guide

Sources

- Hipper, K. (2001) Smugglers All, Larks Press

- Holmes, N. (2008) The Lawless Coast: Smuggling, Anarchy and Murder in North Norfolk in the 1780s, Larks Press

- Muskett, P. (1997) English smuggling in the eighteenth century, PhD thesis The Open University, DOI: https://doi.org/10.21954/ou.ro.0000e12b

[…] church towers. Although King’s Lynn had its fair share of traditional smugglers (most notably Thomas Franklyn and William Kemball), Shaxton was in a different league. He operated by daylight in warehouses on […]

[…] aged only 25, he owned his own vessel, the “Lively”, in conjunction with another Lynn smuggler, Thomas Franklyn. He recognised that vast profits were to be made importing otherwise highly-taxed commodities, and […]