The Tragedy

In 1808 William Wildblood entered St Margaret’s Church in King’s Lynn, climbed the stairs to the belfry, and using the strong rope attached to the tenor bell, hanged himself by the neck until dead.

In one sense the cause of this tragic event was brass.

Since medieval times men who could afford it had tried to perpetuate their memory by having large brass plates depicting themselves and their wives. They and their former wealth would continue to speak down history through their representations on the church floor. At one stage St Margaret’s had had over 50 such plates reminding the congregation of it’s important (and commercially successful) forebears.

Over the years the large number of brass memorials had been reduced. Some had become worn or damaged and were just sold and melted down. A few brasses were quietly stolen and “repurposed”. A dreadful storm of 8 September 1741 brought the 60 metre spire crashing down through the nave creating the need for major rebuilding and remodelling in the church.

In 1804 William Wildblood gained employment in the church as a sexton and gravedigger. He would have had easy access to the church at times when there were few people around. People started to notice a “positive correlation” between Wildblood’s taking up his job and the disappearance of some of the remaining brasses. There were rumours that they were being sold for a few pence and that the sexton was trying to supplement his meagre income. He was confronted and accused, and being unable to bear the shame, Wildblood took his own life in the bell tower by hanging.

The Survivors

The two remaining brasses in the church are the largest from the C14th in England and are a testimony to the wealth of the men who paid for them to be made. They are latten plates (an alloy of copper and zinc) fitted together. The brasses were most likely made in a Flemish workshop (Tournai in Belgium) and transported to Bishop’s Lynn through it’s well-established trading routes. Apart from Tournai brass craftsmanship being desired because of its quality, there was a temporary hiatus in English brass-making in 1349 and after because of the outbreak the Black Death in London.

Both brasses show idealised characters rather than accurate portraits and the clothes follow the fashion appropriate to the position of the person in society. The figures are bold with staring eyes. The wives have an elegant C14th dress with wimples on their heads. The men have pointed shoes. At the time there were strict regulations about shoe toe length. Only the rich people were allowed to have them pointed. Both brasses have dogs at the feet of the women, and dogs were a symbol of devotion.

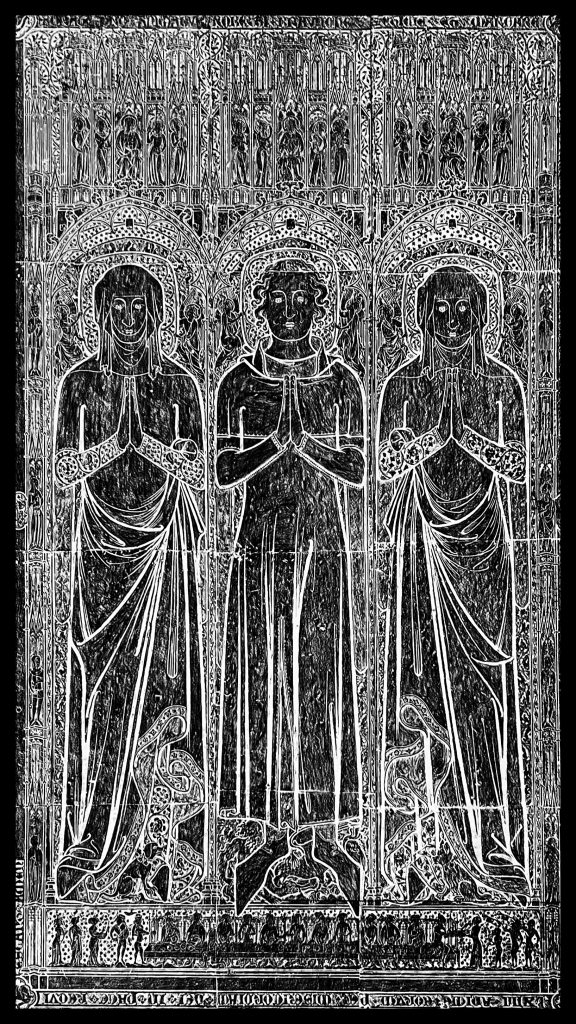

Robert Braunch Brass

Robert Braunch’s brass has the clearer definition of the two and is the slightly younger of the two. It measures 272 by 158 centimetres and depicts Robert with his two wives, Leticia and Margaret.

Robert was a merchant trading in wheat, cloth, iron, leather, cotton, wax and silver. He was mayor in 1349, in 1350/51 and again mayor in 1360/61. It is unknown when his first wife, Leticia, died, but his second wife, Margaret, died in 1361. Robert died in 1364.

Photo © James Rye 2022

The particularly interesting feature of this brass is the panel at the bottom said to depict a Peacock Feast (although some question this interpretation). In 1349, the year of the Black Death, Edward III left London and may have included a visit to Bishop’s Lynn in his travels. We know that Edward III was in Castle Rising in 1349 visiting his mother, the dowager queen Isabella. The long-suffering mayor of Lynn was commanded to send eight carpenters to prepare the castle for the king’s arrival. Peacock Feasts were thrown in honour of people of very high status, and it is thought that this panel possibly celebrates Mayor Robert entertaining Edward III. Whether or not Robert did entertain Edward, the mayor and his descendants wanted him to be remembered as someone entertaining high status guests.

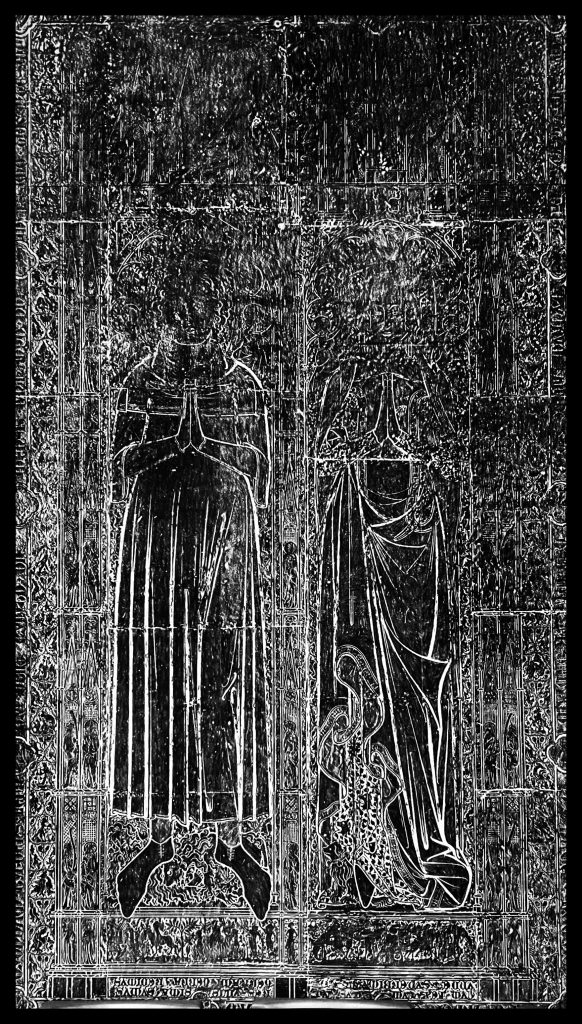

Adam de Walsoken’s Brass

Adam de Walsoken’s brass is the larger of the two, slightly older by a few years, and much more worn. Adam’s brass measures 305 by 175 centimetres and depicts him and his wife, Margaret. Adam died in the year of the Plague (1349), though we do not know if it was the Black Death that killed him.

According to the national taxation record of 1332, Adam was the wealthiest man in Lynn at that time. He was a merchant who dealt in wool and who served as collector of a royal tax in wool in 1338 and collector of national wool customs for a brief stint in 1340. Like most other merchants he also dealt in other goods and in 1333 the community bought two barrels of sturgeon from him. He had been elected mayor of Lynn 1335 and again in 1343.

Photo © James Rye 2022

This brass was originally placed inside one of the church’s main doorways and subsequently suffered from being subjected to a lot of foot traffic. Sadly, the rubbing of the brass has partially obscured one of its most interesting features – the post mill in the band under Adam’s right foot. This is reckoned to be the earliest representation of a windmill in European art.

![The Walsoken Post Mill

Deborah Harlan, Megan Price (2013) HMJ Underhill Archive [data-set]. York: Archaeology Data Service](https://circato.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/hmjuwindmill08-1024x1005.png)

Deborah Harlan, Megan Price (2013) HMJ Underhill Archive [data-set]. York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor] https://doi.org/10.5284/1000234

© James Rye 2022

Book a Walk with a Trained and Qualified King’s Lynn Guide

Sources

- Allen Brown, R. (1978) Castle Rising Castle, English Heritage

- Hillen, H.J. (1907) History of the Borough of King’s Lynn, Vol.1, EP Publishing Ltd

- Richards, P. (2022) King’s Lynn and the German Hanse 1250-1550, Poppyland Publishing

- Webster, J.R.W. (1995) Two Great Brasses, St Margaret’s Leaflet

Websites:

[…] Margaret’s contains two of the largest medieval brasses in the country. The Robert Braunch brass has a panel that is thought to depict a peacock feast, […]

[…] And in St Margaret’s Church in King’s Lynn there is a memorial brass that has a post mill in it. The brass depicts a King’s Lynn Merchant, Adam de Walsoken and his wife, and dates from the around 1349. The post mill is one of the earliest representations of a windmill in European art. (See HERE.) […]

[…] Original Article […]