Any therapist worth their salt will tell you that what we believe will largely influence what we do. If you want to understand actions, talk to people about what they think. People who engage in costly direct protest are usually motivated by a set of strong beliefs. Knowing why someone did what they did, rather than just what they did, would give us a more rounded picture of who they were.

There are at least two men in the history of King’s Lynn (William Sawtry and Thomas Thoresby) whose actions may seem tragic or misguided to someone with a twenty-first century perspective, but which may make more sense if you understand what they were thinking. I explored Sawtry’s beliefs in Part One and propose to examine Thoresby’s in this post.

The Get-Out-Of-Gaol Card Generator: The Off-Set Scheme

Wouldn’t it be great if I told you that if you paid me enough money I could guarantee that I could significantly reduce (even abolish) any legal penalties that you may have collected in your past life and any that you would acquire in the future? It might be great; you might be suspicious about me asking you for money. But I really, really hope that you wouldn’t believe me. The whole idea is preposterous today. However, in 1508 one man used his own money to participate in such a scheme, and not for this life, but for the hereafter. And this man wasn’t unique. Many others had been doing similar things for years. It’s a very powerful reminder that to understand behaviour you really do need to understand beliefs.

As he approached the end of his life in 1508 Thomas Thoresby was worried about penalties – not the ones in this life, but the ones which he firmly believed he would certainly face after death. And they were penalties which, if left unattended, could literally last for eternity. So Thoresby invests considerable money in financing a scheme to minimise his jeopardy.

The Gaol House: Purgatory

Thoresby believed that he, and people close to him, faced an indeterminate period in a kind of spiritual gaol cell after death. At the time the church taught that there were three (not two) possible destinations after death. There was heaven, were a few saintly souls went immediately. There was hell, were several wicked people (especially those excommunicated by the church) went immediately. And there was a place between – purgatory – where most people went while waiting to be made pure enough (purged of their sins) to go to heaven. The worrying thing was that the length of time in spiritual clink could take years.

So a key to understanding Thomas Thoresby is his belief in the doctrine of purgatory (defined at the Council of Lyon in 1274) and the related get-out-of-gaol strategies.

How To Get Out Of Gaol

The church’s theology taught that divine justice demanded the sinner pay for their sin, either in this life or in purgatory. The more “payments” that could be put into the account, the less the risk there would be heavy demands in terms of time spent in purgatory after death.

Ways of making “payment” would be:

- Sorrow for sin, confession, and a penance task given by the priest.

- Repeating a number of prayers such as the Pater Noster, the Ave Maria, the Credo.

- Doing good works, caring for the poor and sick.

- Going on a pilgrimage. (See Pilgrims Through Lynn To Walsingham.)

- Giving money to the church to fund a religious building or for other religious purposes (For example, the people of Lynn who gave money to support the initial building of St Margaret’s Church were given an indulgence of a few days off purgatory for their sacrifice. See also The Sinner and The Dragon.)

- Going on a Crusade to fight and kill the perceived enemies of god. (In 1190 Pope Urban II granted the first absolute indulgence to participants in the First Crusade, and subsequent popes offered indulgences on the occasion of the later Crusades. (At the Battle of Lincoln Fair in 1216 the papal legate, Guala, absolved the Royalist army of all their sins committed since birth, and excommunicated the French and Baron rebels and the people of Lincoln who had supported them.) After 1450 most of the plenary indulgences offered by the pope were for money given towards the crusade in the Mediterranean against the Ottoman Turks.

After the twelfth century indulgences (remission for sin) started to be abused, with the church using them to gain money or to enrich unscrupulous clerics.

Belief In The Power Of Prayer

Some ways of reducing your eternal jeopardy were easier than others. For example, going on a long pilgrimage, or going on a Crusade were both time consuming and potentially very risky (you could die or be killed). However, Thoresby was a rich man and we know from his will that he was quite happy to use his wealth for good purposes (and in the process more easily acquire some eternal capital). He gave money to the pope and to a range of local religious establishments.

Unfortunately the benefit from such acts might be relatively temporary and modest, and he wanted to establish a more reliable, lasting solution that would continue to accrue religious benefit (and reduction of time in purgatory) over a long period of time. He wanted to generate something like the equivalent of spiritual compound interest. And thankfully the church provided the way of doing that (if you could afford it). The church taught that souls are drawn out of purgatory by prayers.

Thomas Thoresby set up what was known as a chantry – an organisation to pay people to regularly, and in perpetuity, pray for certain other people when they were alive and when they were dead. Thoresby College was established – the “college” just being accommodation for the priests who would be required to do the praying. Thoresby funded the building and the salaries and set up land to provide an income so that the praying could go on long after his death.

He did this because he believed there were a direct link between the amount of prayers that were said for him and the amount of time he would spend in purgatory. It was a system to help reduce his jeopardy and help him get out of spiritual gaol.

Breadth And Duration

Photo © James Rye 2021

The system was both impressive and tragic. Thoresby’s chantry was impressive in its width. Before his death he employed sixteen priests; thirteen were to pray for members of the Holy Trinity Guild (of which he was a member), two were to pray for him and his immediate family, and one priest was to teach six boys Latin. Thoresby wasn’t a selfish man.

And it’s important to realise that in his time, Thoresby wasn’t an unusual man. Lots of rich men were leaving endowments to ensure that they were regularly prayed for after death. It was quite usual for monarchs to spend fortunes to ensure that large numbers were paid to pray for their souls after death. For example, Henry V left enough money for 20,000 masses to be said within a year for his soul, and Richard III funded a chantry chapel in York Minster to be staffed by hundreds of praying clergy. Henry VII left enough money for 10,000 masses to be said on his behalf.

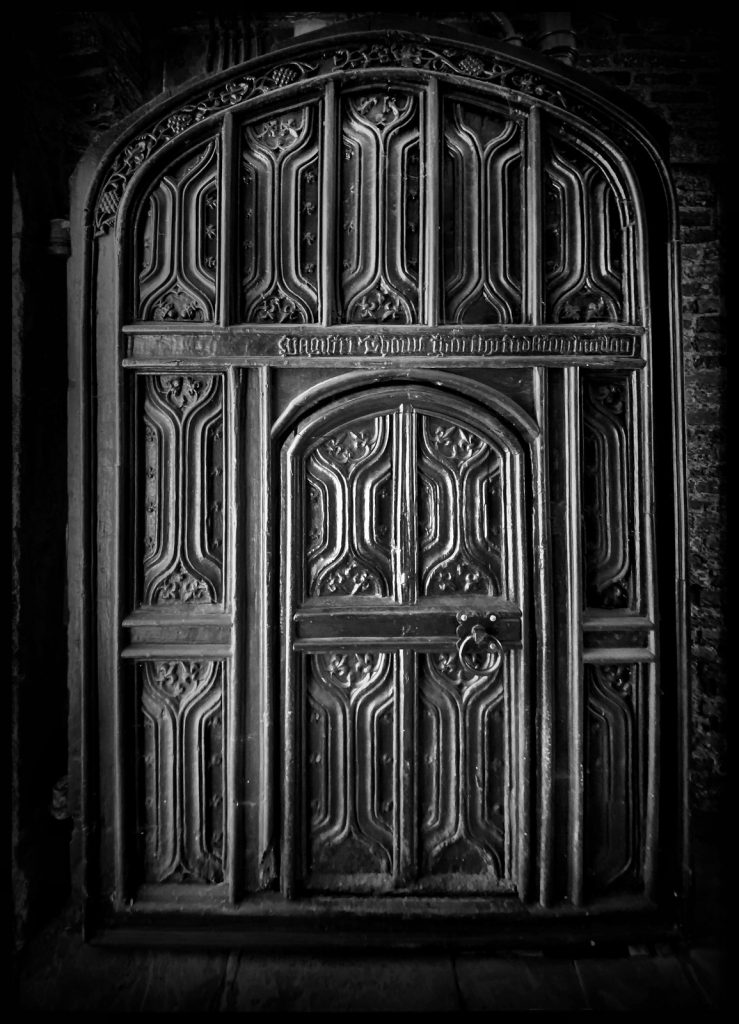

The tragedy is that although the chantry was completed around the time of Thoresby’s death in 1510, in 1547 it was closed by Edward VI (who also closed another 2,373). The “perpetuity” was relatively short. Fairly soon the nervous authorities had three key Latin words (pro ora anima) chiselled off the beginning of the inscription set above the chantry wicket door to remind the priests of their duty as they entered.

(Pro orate anima) Magistri Thomas Thoresby fundatoris huius loci

(Pray for the soul of) Master Thomas Thoresby, founder of this place

From 1547 onwards, whoever was praying for the souls of the dead, it wasn’t to be members of the relatively new Church of England. It wouldn’t be people in Thoresby’s defunct chantry.

Soon after Thoresby’s death, the Middle Ages ended.

© James Rye 2024

See Also

Sources

- Kreider, A. (1979) English Chantries: The Road to Dissolution, Yale University Press

- MacCulloch, D. (2001) Tudor Church Militant: Edward VI and the Protestant Reformation, Penguin

- Marshall, P. (1964) Reformation England 1480-1642, Bloomsbury

- Marshall, P. (2017) Heretics and Believers: A History of the English Reformation, Yale University Press

- Owen, D. (1984) The Making of King’s Lynn, OUP

- Parker, V. (1971) The Making of King’s Lynn, Phillimore