In 1778, at the age of 26, a woman from King’s Lynn published her first novel, “Evelina”. It was an immediate success, captivating readers with witty social satire as it portrayed a young woman navigating the complexities of high society. What is amazing is that the woman, Fanny Burney, had received no formal education (which was normal for women at the time). The novel was also written in secret in a disguised handwriting and was presented to the publisher by Fanny’s brother who pretended to be the author. Initially, when her father, Charles, read it, he had no idea that his daughter was the novelist.

Fanny Burney: Listen, Look, And Learn In King’s Lynn

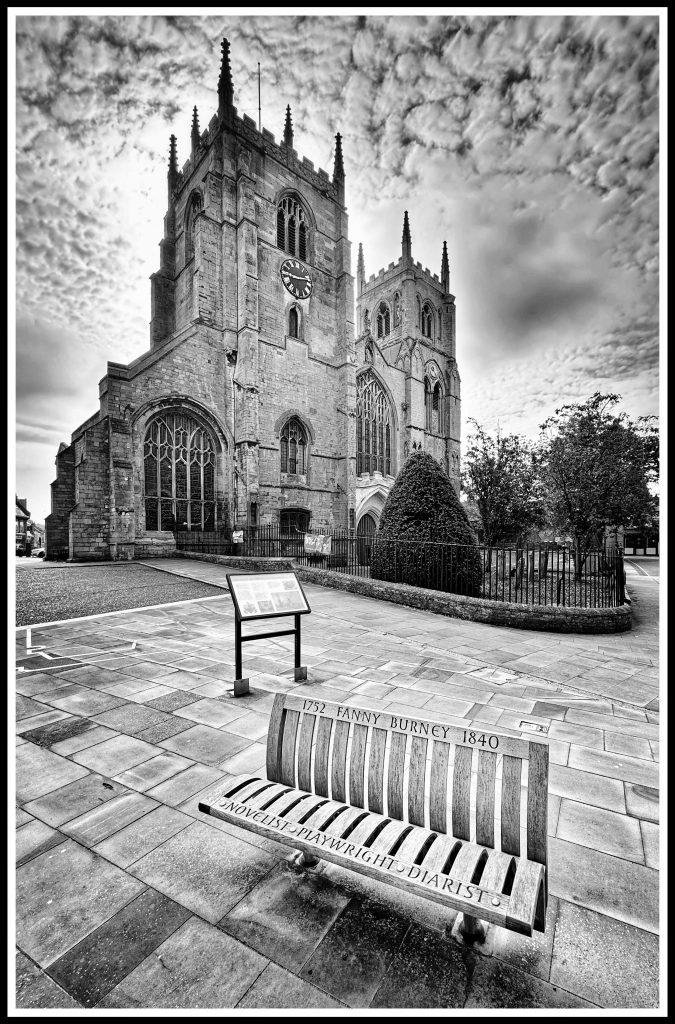

Frances Burney (known as Fanny by the family and friends), was born on June 13, 1752, in Chapel Street, King’s Lynn, Norfolk. She was the third of six highly talented children – four authors, one admiral and a precocious musician – raised by Charles and Esther Burney. When the family moved to a bigger home at 84 High Street the markets and quays of Lynn would have fascinated such an observant mimic as Fanny. The family later moved to Dower House opposite St Margaret’s Church from where she could overlook the river from the bottom of the garden. She spent her formative years honing her skills as an observer of human nature, meticulously recording the nuances of social interactions and mannerisms. These observations would later form the foundation of her novels.

Fanny’s view of Lynn was that of a teenager railing against a restrictive and excessively formal society with its rounds of visits, tea, civilities and playing cards. Thus, for her, assembly room balls were ‘hot and fatiguing’ with dances being 20 minute conversations with your partner. Indeed participants were from a limited number of families, mostly connected or related to each other, which Fanny found claustrophobic.

Photo © James Rye 2024

‘…such a set of tittle-tattle, prittle-prattle visitants! Oh dear! I am so sick of ceremony and fuss of these fall lall people! So much dressing – chit chat – in short a country town is my detestation – all the conversation is scandal, all the focus is dress, and almost all is folly, envy and censure.’

Fanny also commented upon the high society wedding of Alderman Bagge and his rich young heiress Pleasance Case. The huge crowd outside St Margaret’s seemed to be a ‘gauntlet’ faced by the bride after a 15 minute church service –

‘oh how short a time does it take to put an eternal end to a woman’s liberty!…can anything be quite as dreadful as a public wedding – my stars!’

Fanny Burney: A Difficult Context

Fanny was having to contend with two factors which were making her aspirations as a writer far from easy.

The first difficult context was her family. In 1767 Elizabeth Allen became Fanny’s stepmother and she was unimpressed with Fanny’s frequent scribbling – ‘there’s nothing less desirable or elegant than a young lady’s writing’. Because of this Fanny burns the poems, tragedies, plays and novels written up to that time on a bonfire in her London garden. Nevertheless Fanny still enjoyed ‘popping down thoughts from time to time on paper’ and so she secretly wrote the novel “Evelina”.

The second difficult context was the prevailing views about the place women should have in society. Novel writing was not considered a suitable occupation for a lady of Fanny’s social standing. Some in society viewed women writers as unfeminine and their works as potentially immoral. The reason she publishes her first novel anonymously was out of fear that it would not be approved of by her father.

It could be argued that Charles Burney’s attitude to his daughter is (understandably for the time) ambiguous. He is both proud of her and encouraging, and yet, at the same time he is discouraging and restricting. Being a self-educated woman, Fanny is dependent on her father’s access to the largely male bastions of literary circles to help increase her recognition, and Charles seems quite happy to provide this. From his home in London Burney introduced Fanny to a brilliant social circle. Visitors included Hester Thrale (a patron of the arts), David Garrick, Edmund Burke, Richard Sheridan, and Samuel Johnson. Her father’s friendship with the literary critic Samuel Crisp, also had a profound impact on her development as a writer. Crisp encouraged Burney’s literary pursuits and became a trusted confidant to whom she addressed her earliest journal entries, capturing the lively musical evenings at the Burney household.

However, Charles actively prevented her from pursuing a career as a playwright. Despite her play “The Witlings” being accepted by the Drury Lane Theatre, her father intervened and stopped its production. He thought it was improper for a woman to write for the theatre. He also disliked the satirical criticism of many in the upper classes who were his patrons.

Fanny Burney: Novels Of Manners And More

“Evelina; or, The History of a Young Lady’s Entrance into the World” was groundbreaking in that it relied on the development of character and plot rather than on sensationalism. Burney’s ability to capture the nuances of language and social dynamics was instrumental in the novel’s success. Her keen observations and attention to detail brought to life the intricacies of 18th-century English society. In all, she wrote four novels, eight plays, one biography and twenty-five volumes of journals and letters.

She has gained critical respect in her own right, but she foreshadowed such novelists of manners with a satirical bent as Jane Austen and William Makepeace Thackeray. Her early novels were read and enjoyed by Jane Austen, whose own title “Pride and Prejudice” derives from the final pages of ”Cecilia”. Thackeray is said to have drawn on the first-person account of the Battle of Waterloo recorded in her diaries while writing his ”Vanity Fair”. Virginia Woolf believed Fanny to be ‘The Mother of English Fiction’.

Fanny’s writing career coincided with the rise of the Enlightenment ideals of reason, individualism, and social reform. Her novels explored themes of courtship, marriage, and the struggles of women in a male-dominated world, reflecting the early feminist perspectives emerging at the time. However, in addition to the social satire, her writing also covers topics which many would have considered improper for a woman to discuss. Her works include descriptions of guns, duels, suicides, highway robberies, fighting and attacks.

Fanny can also be thanked for adding to the lexicon of written English. She uses modern slang and introduced several new words and phrases: ‘dabble’, ‘skipping rope’, ‘lunch party’, ‘shopping’, ‘school girl’, ‘coach party’, ‘seeing sights’, ‘funny’, ‘grumpy’, ‘to elbow’.

Fanny Burney: Other Interesting Facts

- Between 1786 and 1790 she held the post of “Keeper of the Robes” to George III’s wife, Queen Charlotte. During that time she witnessed George III’s ‘madness’.

- In 1793, when she was 41, Fanny married Alexandre d’Arblay, a French émigré living in England. She ends up having to spend 10 years living in France because of the renewal of the Napoleonic Wars.

- In 1811, at the age of 59, Fanny undergoes a mastectomy without anaesthetic because of a breast cancer diagnosis. You can read her account of the horrific experience here. She survived the horrendous operation and lived for another 20 years.

Fanny Burney: The King’s Lynn Bench And London The Corner

In recognition of Fanny’s achievements and of her time in the town, the King’s Lynn Civic Society commissioned a bench to be installed in the Saturday Market Place in front of The Minster where Fanny was christened and near one of the houses where she lived. The oak bench was designed and produced by Toby Winteringham, a local furniture maker based King’s Lynn.

As well as having plaques in the King’s Lynn, Fanny is one of the few female writers celebrated in the Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey. Only nine percent of the memorials are to women, but Fanny is there alongside Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Bronte, Elizabeth Barrett-Browning, George Eliot, Elizabeth Gaskell, and Jane Austen.

Also, Fanny joins John Capgrave and Margery Kempe in being part of King’s Lynn’s contribution to our literary heritage.

© James Rye 2024

Sources

- Chappell, J. (2022) Fanny Burney 1752-1840, Unpublished paper presented to King’s Lynn Town Guides

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b05r3zjk

- https://www.mcgill.ca/burneycentre/files/burneycentre/styles/wysiwyg_large/public/fanny-burney1.jpg?itok=YGmfiQae

- http://womenshistory.info/fanny-burney/

- https://ivypanda.com/essays/male-sensibility-in-frances-burneys-evelina/

- https://fliphtml5.com/xrgx/akdc/basic

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frances_Burney

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Fanny-Burney

- https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/jun/22/the-evil-was-profound-fanny-burney-letter-describes-mastectomy-in-1812

- https://www.literaryladiesguide.com/author-biography/fanny-burney/https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b05r3zjk

- https://www.amusingplanet.com/2019/09/fanny-burneys-gruesome-mastectomy.html?m=1

[…] and had numerous children, many of whom became notable in their own right. His eldest daughter, Frances Burney (1752–1840), was a gifted novelist whose books Evelina and Cecilia were literary […]