The French Are Coming

Ironically, although King John had proved himself very capable of hostage taking and demanding ransom, it was not King John who used this tactic against the people of Lynn in the summer of 1216, but the agents of John’s latest rival, the French Prince Louis.

The first few years of the thirteenth century were an uncertain time for many people. After all, the man who has been described as “the evil king” (John) was on the throne. However, in 1216, Lynn makes its second of three appearances as a footnote in King John’s story. And some rich people in Lynn are made to feel a significant pinch.

King John and The Charter: Lynn’s First Footnote in the Life of King John (1204)

For some, 1204 was a relatively good year: for King John, it wasn’t particularly good. Since the Norman Invasion of 1066 most of the English aristocracy had land both in England and what is now known as France. In 1203 it is said that you could walk from the Scottish border, through England and France to Spain, and you could follow a route where the ground that you trod on could be called “English”. By the end of 1204 John had lost most of France and would spend the rest of his life trying to get it back.

© James Rye 2025

However, 1204 could be said to be a good year for the people of Lynn. The town, which had been established a century earlier, was developing into a successful port. The tax returns for that year show that it was the third busiest port in the country after London and Southampton. Its recently developed hinterland, giving it access to and from ten counties, was clearly starting to make the merchants rich.

At the request of John de Grey, Bishop of Norwich, King John gave Lynn the right to be a free borough, with rights of local jurisdiction, and freedom from tolls except in London. The town was also given the right to have a merchant guild. To help the town understand what this meant in practice, it was told to follow the law and custom of Oxford. The burgesses of Oxford were given the power to make decisions if disputes about interpretation arose. (See King’s Lynn’s Charters.)

To stop the town enjoying too much unbridled liberty, the existing rights of the Bishop of Norwich and of the Earl of Arundel over the town were to continue unchanged. This clause was bound to be a source of friction (depending on the personalities involved) and over 150 years later, there was a riot in Lynn and an attempt to kill the bishop.

But in 1204, for the people of Lynn, things were good.

King John and The Hostage Taking: Lynn’s Second Footnote in the Life of King John (Summer 1216)

It is fair to say that King John (1199-1216) did not spend his 17 year reign treating others fairly. He had his cousin Arthur murdered (Arthur was a theoretical rival to the throne). John was known to be vindictive and cruel, with a tendency to starve captives in prison. He tried to gain control of the church and introduced unjust laws to gain money and keep the aristocracy indebted to him. He was not popular. (See here.) After the king’s death one chronicler (Matthew Paris) wrote: “Foul as it is, Hell itself is made fouler by the presence of John.”

Ironically, although King John had proved himself very capable of hostage taking and demanding ransom, it was not King John who used this tactic against the people of Lynn in the summer of 1216, but the agents of John’s latest rival, the French Prince Louis (who almost became Louis I of England, and who did go on to become Louis VIII of France).

It was no surprise to many that the promises John made in Magna Carta (1215) were not kept. War with the barons was inevitable. In the midst of the turmoil created by John, the barons looked across the Channel to the powerful and stable royal line of France for help. In contrast to the violence of the Plantagenet history, the French had experienced 200 years of relatively smooth transfer of power from father to son. Philip was now old, but his son Louis, a proven warrior with a reputation for being moral and just, was a very attractive option.

Louis was invited, and on 21 May 2016 his invasion fleet arrived at Isle of Thanet. Louis soon enjoyed success. John, nicknamed “Soft Sword” (Johannem molle gladium) because of his avoidance of battles, saw Louis arrive but then retreated to Dover, then to Guildford, then to Winchester, then to Corfe. The barons already held London for Louis while he took Sandford, Canterbury, Rochester, Guildford, Winchester, Porchester, and Marlborough. Many of the barons who had initially decided to stay loyal to John defected to Louis – most notably the earl of Salisbury, John’s half-brother, William Longsword.

While Louis was occupied in trying to capture the castle at Dover, his followers had been very busy elsewhere. Carlisle, York, Lincoln (but not the castle) had fallen.

About this time Louis made an incursion into the eastern part of England, pillaged the cities and towns of Essex, Suffolk, and Norfolk, and finding the castle of Norwich deserted he garrisoned it with his own soldiers and imposed a tax on all those districts ; he also sent a large force against the town of Lynn, which he reduced, and, taking the inhabitants away prisoners, he compelled them to pay a heavv ransom ; after this the French returned with great booty and spoil to London.

Roger of Wendover

And Robert Fitzwalter (one of Louis’ main supporters who had been elected “Marshal of the Army of God and Holy Church”) had success in the East. Norwich was taken, and a brief report in the chronicle of Roger of Wendover intriguingly tells us that Lynn was attacked and that several people were taken hostage in order to be ransomed back. This proved a rewarding strategy as Hillen says that a similar fate befell the people of Yarmouth, Dunwich, and Ipswich.

At the time of writing I have not been able to discover further information about this incident. (Do contact me if you know more.) We don’t know how many people were taken, and how much money was involved. (It sounds painful. Roger of Wendover uses “heavy ransom” and “great booty”.) One can only guess that it probably involved some of the rich merchants living in the properties near the quay and around the Market Places, as well as some of the recently created Guild Officers (the two groups probably overlapped). They would have been wealthy people as there would be little point in trying to extort money from people who couldn’t pay. Once the ransom had been achieved, the troops returned with their booty to London.

While it was undoubtedly unpleasant for the people of Lynn, it could have been so much worse. On 24 June 1216 John arrived at Winchester and ordered the suburbs of the city to be burned to the ground. The primary purpose was to deny shelter to an enemy force chasing him. A year later the rebuilt city suffered exactly the same fate when William Marshall was fleeing from Louis. Lynn could easily have been destroyed by Louis’s supporters to stop the important port falling into John’s hands.

King John and The Mud: Lynn’s Third Footnote in the Life of King John (Autumn 1216)

King John had given a charter to the important port of Bishop’s Lynn (now King’s Lynn) in 1204, and on October 9 1216 he arrived in Lynn from Boston and Spalding, hoping to get supplies for his northern castles. Having been richly entertained and also given a large some of money by the burghers of Lynn who were so pleased to see him following their recent experience, John left on 11 October and rode ahead.

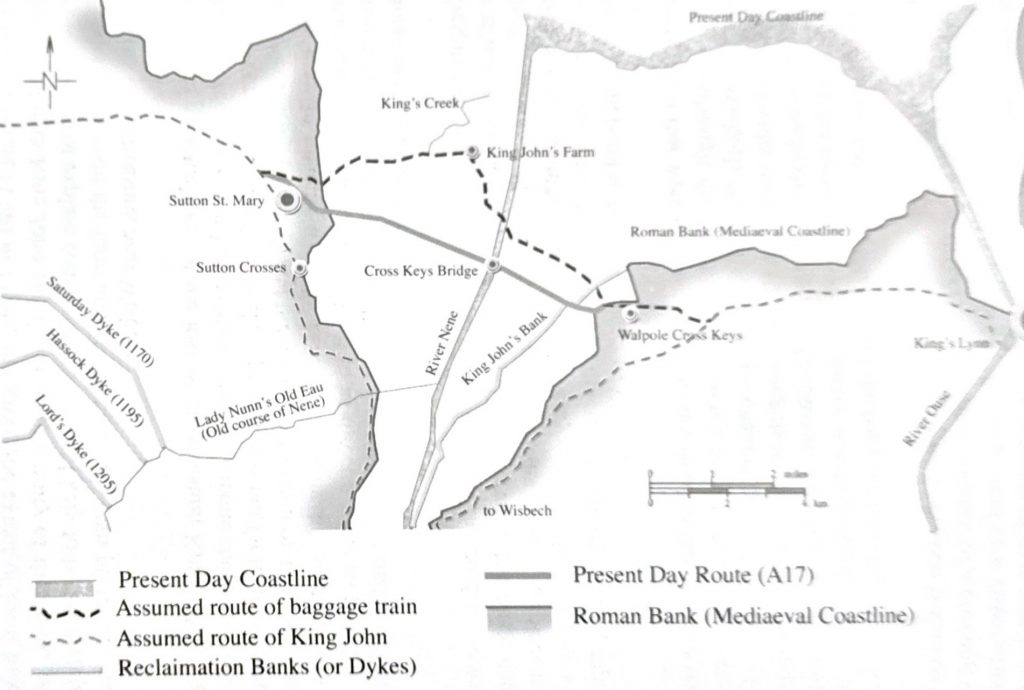

Unfortunately his baggage train cart drivers wanted to avoid the longer road route and tried to take the known shortcut across the Wash from Cross Keys to Long Sutton.

It was not unusual for a king to be separated from his baggage while they were on the move. Heavy carts were slow, travelling at only two and a half miles per hour, and could be further delayed by poor road conditions and swollen rivers. Medieval communications suffered from a significant shortage of bridges. In contrast, the roads were suitable for well-mounted horsemen, allowing express messengers to travel 35-40 miles in a day. The king often moved my court 20-30 miles in a day, occasionally covering even greater distances.

Sadly his servants got their timings wrong and many of them and John’s baggage were destroyed in the mud by the incoming tide. John struggled on from Swineshead to Newark where, on October 18, he dies.

John almost certainly died from dysentery caught in Bishop’s Lynn – though a surfeit of peaches and new cider, weariness from excessive frantic travel, the heartbreaking news of defeats by his enemies, and the losses of his religious relics and money in the Wash, probably all combined to play a part.

At least one of the Lynn merchants robbed in the summer of 1216 must have looked across the mud of the Wash and wondered if John’s treasure would ever reveal itself. It never has done, so far.

© James Rye 2022

See also: The Battle of Lincoln Fair

Sources

- Appleby, J.T. (1959) John, King of England (1167-1216), Knopf

- Giles, J.A. (1849) Roger of Wendover’s Flowers of History Vol II, Henry G. Bohn

- Hanley, C. (2016) Louis: The French Prince Who Invaded England, Yale University Press

- Hillen, H.J. (1907) History of the Borough of King’s Lynn, Vol.1, EP Publishing Ltd.

- Jones, D. (2013) The Plantagenets: The Kings Who Made England, William Collins

- Jones, D. (2015) In the Reign of King John: A Year in the Life of Plantagenet England, Head of Zeus Ltd.

- Morris, M. (2015) King John: Treachery, Tyranny and the Road to Magna Carta, Penguin Books

- Vincent, N. (2020) John: An Evil King?, Penguin Books

- Warren, W.L. (1961) King John, Eyre & Spottiswoode

- Waters, R. (2006) The Lost Treasure of King John: Second Edition, TUCANNbooks

- Weir, A. (2020) Queens of the Crusades: Eleanor of Aquitaine and Her Successors 1154-1291, Vintage

Websites

- https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryMagazine/DestinationsUK/Kings-Lynn-Norfolk/

- https://www.british-history.ac.uk/hist-mss-comm/vol11/pt3/pp185-209

- https://nrocatalogue.norfolk.gov.uk/index.php/borough-of-kings-lynn-1204-1974-kings-lynn-norfolk

- https://norfolkrecordofficeblog.org/2016/10/21/one-of-kings-lynn-borough-archives-earliest-documents-the-charter-of-king-john-to-the-burgesses-of-lynn-14-september-1204/

- https://enwik.org/dict/Robert_Fitzwalter

[…] See also Hostage Taking in Lynn. […]

[…] Lynn) features as a significant footnote on three occasions in any history of King John (see Hostage Taking In Lynn). King John had a lot on his mind in 1204 having just lost virtually all of the English territory […]

[…] Hostage Taking in Lynn […]

[…] Original Article […]