In the later Middle Ages, Lynn was home to several friaries. The Dominicans, Franciscans, Carmelites, Austin Friars, and for a time even the lesser-known Friars of the Sack, all had houses here. The names “Blackfriar”, “Greyfriar”, “Whitefriar” and “Austin” can all be found in Lynn’s modern street names reflecting the areas where their buildings were.

Lynn was remarkable for having a a concentration of friaries, found in only a few English towns.

Their presence shaped the religious and social life of the town for three centuries. They drew on royal gifts, relied on local benefactors, and extended their sites as funds allowed. Yet within a few weeks in the autumn of 1538, every one of them surrendered to the Crown, and centuries of friar life in Lynn came abruptly to an end.

What is the Difference between Friars and Monks?

Lynn also had a group of Benedictine monks.

Monks

Monks were members of religious communities who lived a contemplative and secluded life, often in monasteries, following vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. Monks usually remained fixed in one place, dedicating themselves to prayer and work within their monastic setting.

Lynn’s Benedictine monks served the church of St Margaret (now King’s Lynn Minster). The Benedictine Priory had been founded in 1100 by Herbert de Losinga and was tied both spiritually and economically to Norwich Cathedral. The Benedictine monks formed the first and main monastic community, focusing on worship, education, and land-management around the Minster. The friars arrived later in the thirteenth century.

Friars

Friars were members of mendicant religious orders who also followed vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience but lived and worked among laypeople, travelling and engaging in preaching, teaching, and charitable works. Friars depended on voluntary offerings rather than property or fixed revenues, and their commitment was often to a broader community or province instead of a specific locality.

A “mendicant” was a member of a religious order whose way of life involved relying on charitable donations or alms for support, typically embracing poverty, travel, and service among society rather than remaining secluded or self-supporting. Mendicant friars – like the Franciscans and Dominicans – stood apart from monks due to these core practices.

The Dominican Friars (Blackfriars)

The name Blackfriars comes from the black cappa (cloak) and hood Dominican Friars wear over their white habits during the winter and when outside the cloister.

The priory of the Friars Preachers, or Dominicans, was founded towards the close of Henry III’s reign by Thomas Gedney. It stood on the east side of the town, between Clow Lane and Skinner Lane (approximately in the area of St James’ Car Park). Dedicated to St Dominic, the church and convent were already substantial by Edward I’s reign, with space for around forty friars.

The site was enlarged in the fourteenth century and it was given a reliable water supply from Brookwell, a spring at Middleton some four miles away, donated by William Berdolf. The house enjoyed royal attention. Edward I, while at Gaywood in 1277, sent money to cover the friars’ food for a day, and repeated the gift later. John de St Omer, mayor of Lynn in 1285, supplied wine for St Dominic’s feast. In 1300 Edward I contributed again, while Edward II, on his arrival in 1326, gave for the upkeep of forty-five friars. Edward III followed suit in 1328.

The priory also hosted three provincial chapters of the Dominican order, in 1304, 1344, and 1365, with kings providing generous subsidies for the expenses.

Around 1486 fire caused heavy damage, and even two decades later the buildings were still not fully restored. In 1476 the master-general allowed the prior to receive fresh benefactors, directing their alms towards repairs.

By the time of the Valor Ecclesiasticus in 1535, the priory’s resources were small. Prior Thomas Lovell reported only a tenement in Lynn rented at 10s. a year and a meadow worth 8s. Three years later, the house was surrendered. The document, left undated, bore the signatures of Lovell, Robert Skott, and other members of the community.

Noted priors: William de Bagthorpe (1393); John Braynes (1488); William Videnhus (1497); Thomas Lovell (1535).

After the Dissolution, the site was granted to John Eyre, one of the king’s auditors. He secured large portions of former monastic land, including estates from Bury St Edmunds, but his wealth brought little lasting fortune. He died childless.

The Franciscan Friars (Greyfriars)

The followers of Francis of Assisi wore a rough grey-brown tunic tied with a cord. In England the colour was usually described as grey, so the Franciscans became known as Greyfriars.

The Greyfriars of Lynn were established by Thomas Feltham. The Franciscans were the first friars to arrive in Lynn and were here by 1230. The community quickly became significant: John Stanford, provincial of the Franciscan order, who died in 1264, was buried at their house in the town.

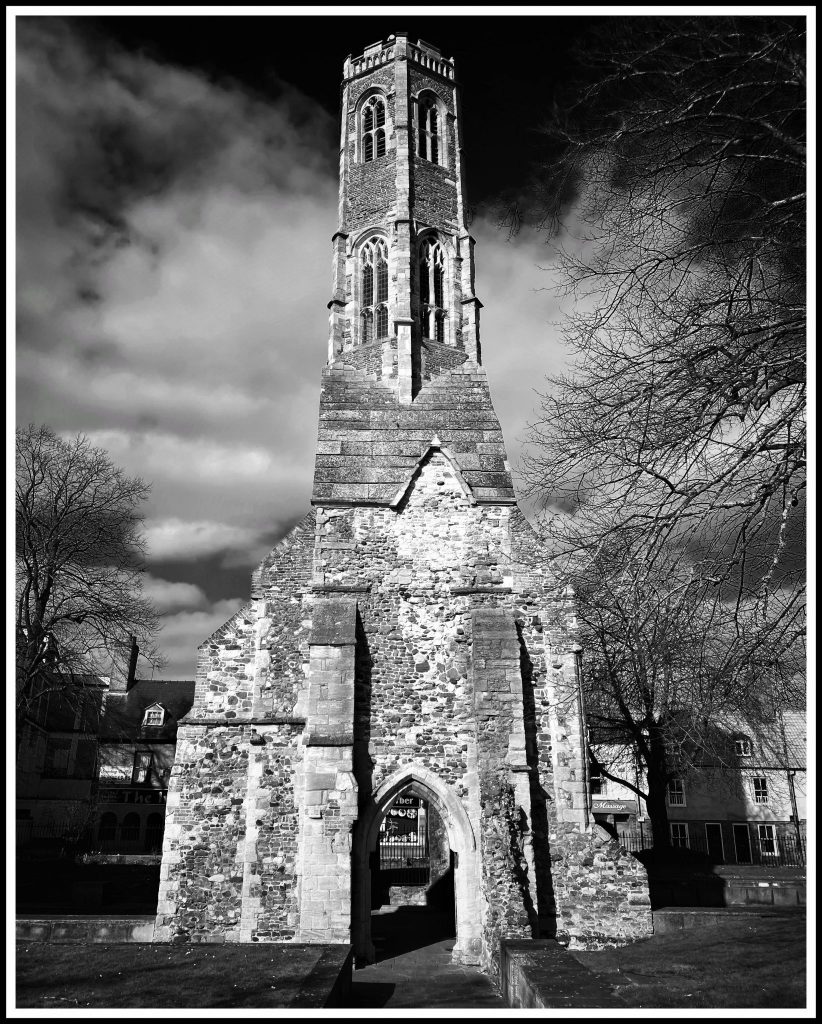

In 1314, licence was obtained for the friars to keep a mill at North Runcton, known as Bukenwelle, which they had acquired without formal permission. They channelled water from its spring by underground conduit to their Lynn friary, ensuring a fresh supply for their community. The Lynn Greyfriars building comprised a nave and a choir divided by a walkway that was later (C14th, C15th) adorned with a bell tower. It is this bell tower above the walkway that remains.

Photo © James Rye 2021

By the fourteenth century many Franciscan churches in Britain had a distinction not found anywhere on the Continent. They had a walkway separating the nave from the choir/chancel, with a slender bell tower or bell turret over the walkway. This formed an entrance passage which led directly to the street – a symbol of the friars’ close contact with people. The Lynn tower is the best surviving example in the country of a Mendicant tower with a passageway.

In addition to the Friary Church there were buildings on the south side comprising a dormitory, a hospital, a refectory, a chapter house, a kitchen, and a hall, with access via a cloistered walkway. From 1314 the site was fed by a water supply from North Runcton.

Like the Dominicans, the Franciscans gradually expanded. It is difficult to know the precise numbers of Greyfriars in the town. There were ten friars in 1320 at the beginning and nine in 1539 at the end. According to Rowlands, the average size of Franciscan establishments throughout the country (1230-1538) was twelve to fifteen. The Britain Express website claims that in 1325 the Lynn group comprised thirty-eight friars. In 1365 they secured permission to add two extra buildings to their site.

Their end came on 1 October 1538, when the house was formally surrendered. The document was signed by Edmund Brygat, the warden, together with nine others.

The Carmelite Friars (Whitefriars)

Their habit was white, with a dark brown cloak. In England the striking white garment made the stronger impression, so they were widely called Whitefriars. The Whitefriars settled on the south side of Lynn, close to the river. According to Blomefield, the house was founded by Lord Bardolph towards the end of Henry III’s reign.

The first surviving reference to them is from 1261, in a dispute over an obstructed lane. In 1277 Edward I granted them six oaks from Sapley Forest for church building, though the timber proved unsuitable. He then instructed his steward to provide better trees from elsewhere in the royal woods. In 1285 the friars were given licence to close a lane beside their churchyard, provided they created a replacement of equal size on their own land. The Bardolph family remained closely connected: William, Lord Bardolph, died in 1386 and was buried in the Carmelite church.

Evidence also links the Hastings family to the house. In a deposition made during Henry IV’s reign, Friar Peter of Lynn, the sub-prior, testified that the Hastings arms had been painted in the priory for forty years, and their banner had been displayed for nearly half a century.

At the time of the 1535 Valor Ecclesiasticus, the Carmelite property was modest: land within the precinct worth 33s., and a plot outside valued at just over 2s. The friary was surrendered on 30 September 1538, signed by Prior Robert Newman and ten brethren. The house’s seal, dating from the fourteenth century, survives. It shows two niches: on the left the Virgin with the Christ Child, on the right St Margaret piercing the dragon’s head with a cross, holding a book in her other hand.

The Augustinian Friars (Blackfriars, Austin Friars)

Their habit was black, so in England they were often called Blackfriars. That label, however, is more often associated with the Dominicans, who also wore black cloaks over white tunics. In practice both orders were sometimes called Blackfriars, but Dominicans are the ones most consistently given that nickname. To avoid confusion, Augustinian Friars were often simply called Austin Friars,

The Austin Friars settled on the north side of Lynn early in Edward I’s reign. By 1295 they were firmly established, when Margaret de Suthmere gave them a plot of land measuring 100 by 80 feet.

Their site steadily grew through benefactions. Thomas de Lexham granted them land in 1306 and again in 1311, and Humphrey de Wykene gave a further plot in 1329. By 1338, Robert de Wykene’s grant of land allowed a major enlargement, likely accompanied by rebuilding. Additional gifts in 1364 and afterwards extended their property further.

In 1383 the bishop of Norwich allowed the friars to tap a spring at Gaywood and run a conduit beneath his demesne to supply their house with water. More land followed in the reigns of Henry IV and Henry V. At a local level it is almost inevitable that the Augustinians under John Capgrave would have rubbed up against vested interests, particularly centred on the church of St Margaret’s.

The mission of the Augustinians – to minister to the local townsfolk ill-served by their parishes – helped gain them both popularity with the people and the suspicion of those in power. The Benedictine Monks of Norwich who were rectors of St Margaret’s successfully fought to maintain the growing Lynn as a single parish and prevent the establishment of a separate parish around St Nicholas. The willingness of the Austins to offer laypeople burial within their friaries instead of in the parish gave any conflict a financial dimension. An entry in St Margaret’s accounts for 1445-46 allocating 56s 5d “circa destruccionem oppinionis magistri Johannis Capgrave predicantis” (”concerning the destruction of the opinion of John Capgrave, the preacher”) suggest that the relations were not always entirely cordial.

By the time he was host to Henry VI in 1446 Capgrave had achieved the rank of prior. The royal visit was initially anything but peaceful. Somebody used the occasion to make false accusations against the local Augustinians. However, Capgrave defended the order and the king was impressed.

At this time we know that the friary housed thirty priests and sixteen students, along with various deacons and members of minor orders. It was (or became) during Capgrave’s tenure, the largest Augustinian friary in England.

Capgrave’s administrative abilities must have impressed his fellow Austins as he was unanimously elected as Prior Provincial of England in 1453 and again two years later. As Prior Provincial he had responsibility for forty-one friaries throughout England. It has been said that Henry VII wished Capgrave to be canonized and some of this friar’s early biographers refer to him as “Beatus”, which was an allusion to Henry VII’s wish.

By 1535, under Prior Thomas Potter, their possessions included three tenements in Lynn, valued at 26s. 8d. a year. Like the Carmelites, they surrendered their house on 30 September 1538, with Prior William Wilson and ten others signing the document.

The Friars of the Sack

The Friars of the Sack were a short-lived mendicant order in the thirteenth century, and their English nickname came directly from the rough material of their clothing. They wore a plain, sleeveless tunic made of coarse sackcloth, usually grey or brown, tied at the waist with a rope. It was deliberately austere, intended to mark their poverty and penitential way of life. Contemporary chroniclers sometimes described them as Fratres de Sacco (“Brethren of the Sack”), which was simply translated into English.

The least-known of Lynn’s friars were the Friars of the Sack, or de Penitentia. Their house was founded in the thirteenth century, but the order never prospered. Suppressed in France in 1293 for lack of numbers, its English houses followed in 1317, when members were absorbed into the larger mendicant orders.

At the time of suppression, Robert Flegg, prior of the Lynn house, was head of the order in England. A record from 1277 refers to his right to hold certain houses in the town.

With their dissolution, Lynn’s small community of Friars of the Sack disappeared, leaving little trace compared with the larger orders.

© James Rye 2025

Book a Walk with a Trained and Qualified King’s Lynn Guide

Sources

- Augnet http://augnet.org/en/history/people/4318-john-capgrave/

- Britain Express https://www.britainexpress.com/counties/norfolk/abbeys/greyfriars-tower.htm

- British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/norf/vol2/pp426-428

- Heritage Norfolk https://www.heritage.norfolk.gov.uk/record-details?MNF5477-Greyfriars-Tower-and-Tower-Gardens-King’s-Lynn

- Page, W. (1906) ed. ‘Friaries: Lynn’, in A History of the County of Norfolk: Volume 2, British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/norf/vol2/pp426-428

- Rowlands, K.W. (1999) The Friars: A History of the Medieval Friars, The Book Guild Ltd

- Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greyfriars,_King’s_Lynn

- Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Capgrave

- Winstead, K.A. (2007) John Capgrave’s Fifteenth Century, University of Pennsylvania Press