The Battle of Lincoln Fair, 1217

King John’s Death

When King John left Bishop’s Lynn (now King’s Lynn) on 11 October 1216, little did he realise that his death seven days later, or that the crisis which his appalling rule had caused, would be brought to a head. John had repudiated the promises he made a year earlier in signing Magna Carta and the frustrated barons had invited Louis from France to seize the throne while John was still alive. Louis’ troops had already captured London, Carlisle, and York. Although Lincoln Castle had refused to surrender to the rebel army, the city itself had fallen.

Unless an army loyal to John’s young son (Henry III) could soon defeat the rebels, there was a realistic prospect that England would be ruled by the Capetian monarchy. The battle, which was to take place some seven months after John’s death and merely 20 miles from where he died in Newark, was to be one of the most significant in English history.

A New King Is Crowned

The new king, John’s nine-year-old son, Henry III, was crowned at Gloucester Cathedral on 28 October, 10 days after his father’s death. It was decided to crown the new king immediately as Louis had been proclaimed king in London. In the absence of the Archbishops of York and Canterbury it was the papal legate, Guala, who conducted Henry’s coronation. The 70-year-old, but effective and loyal William Marshall, Earl of Pembroke, was persuaded be the young king’s regent.

The Castle

In early 1217 the Anglo-French rebel forces under the young Comte de Perche arrived in Lincoln to reinforce Gilbert de Gaunt who had been conducting a long siege of Lincoln Castle. The castilian, Nicholaa de La Haye, had been left in charge of the castle by John, and she was faithful to the royal cause.

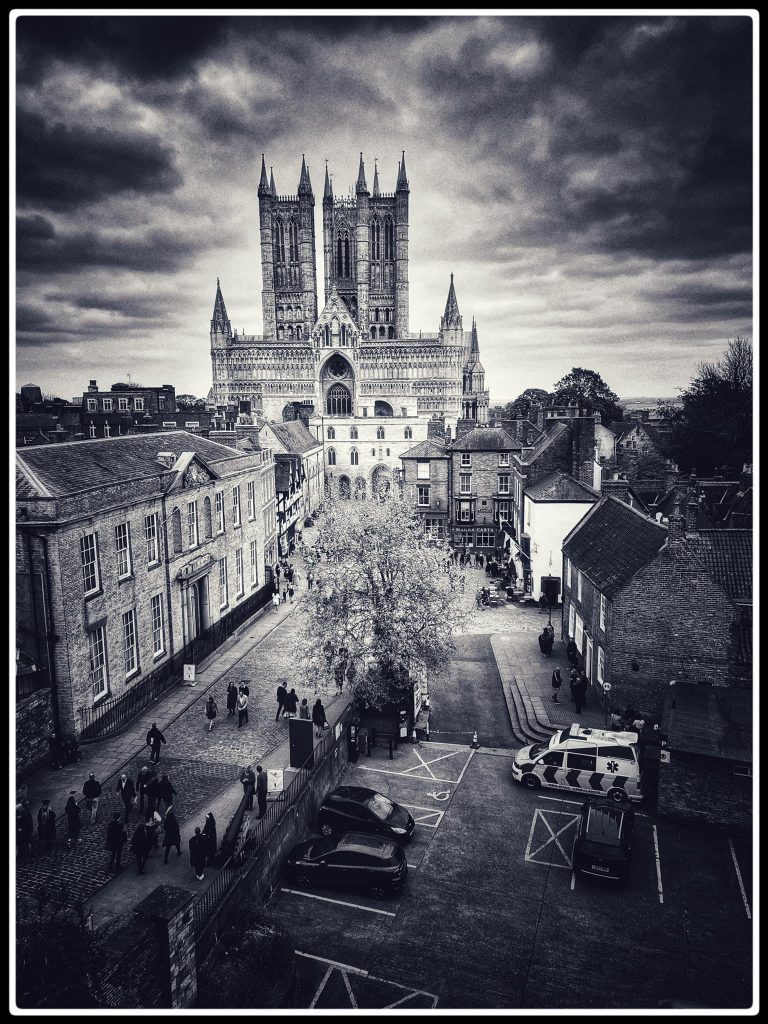

The castle itself was one which was difficult to capture. It has a curtain wall stretching over a third of mile and it sits on an impressive steep hill opposite the cathedral. Three sides of its curtain wall are within the city limits. There is a steep drop to the south. It is not an easy castle to attack and almost impossible to encircle. Any attacking forces would have to concentrate on the west or east gates.

From March to mid-May 1217 siege machinery provided by Louis to de Perche bombarded the south and east walls of the castle, and further rebel forces were called for. When they eventually arrived, this meant that half of Louis’ total force in England was now outside the castle gates.

The Battle Of Lincoln Fair

The concentration of rebel forces at Lincoln provided Marshall with an opportunity for a decisive battle. If he could win it would hamper the hopes of Louis and the rebel barons and prevent them getting influence in the north of the country. There was also the chivalrous need to rescue a lady in distress.

Photo © James Rye 2022

On 17 May Marshall mustered the Royalist army at Newark (406 knights, 307 crossbowmen, numerous followers). The papal legate, Guala, absolved the Royalist army of all their sins committed since birth, and excommunicated the French. Guala also unfairly excommunicated people of the city because he felt they had given in to the French too easily. This excommunication was used to justify a lot of destruction later on. The ensuing struggle would now be a crusade and the royalist army, like all good crusaders, sewed linen crosses on the shoulders of their tunics.

On 20 May the Anglo-French (600 knights and 1000 infantry) refused to engage with Marshall in a battle on the plains outside the city walls and withdrew into the city, convinced that Marshall’s troops were not strong enough for an all-out assault on the city. Some of Marshall’s troops got into the castle via a postern gate in the west wall and crossbowmen then rained bolts onto the Anglo-French army from the ramparts above the East Gate looking towards the cathedral.

Eventually Marshall’s main force broke through the city’s North Gate and spilled into the space between the castle and cathedral taking the enemy by surprise. Almost simultaneously another Royalist force broke through a West Gate. The Royalist soldiers inside the castle now left the ramparts and joined the fighting outside. Vicious close-quarter combat took place between the castle and the cathedral and in the narrow streets nearby. The Comte de Perche was killed and the rebels started to retreat down the steep hill pursued by the Royalist troops. Many fleeing rebels were killed or captured because the South Gate was notoriously difficult to get through and was possibly blocked by a cow.

Afterwards

The battle was over in six hours. 46 rebel barons and 300 knights surrendered. Only three knights (including de Perche) died in battle.

The fact that the papal legate had pronounced excommunication on the Anglo-French force and the people of the city meant that the destruction of property and people that followed seemed justified. It was considered a just punishment for the city that had supported the rebels. Even the churches were plundered. We do not know how many women were raped (the “insult” referred to below) or how many died trying to escape. It is entirely possible that the sacking of the city after the battle resulted in more casualties than the battle itself. (Ironically, in the first Battle of Lincoln in 1141, the city was sacked afterwards because the people had supported King Stephen and not the rebels loyal to Empress Matilda.)

Roger of Wendover wrote: “After the battle was thus ended, the king’s soldiers found in the city the waggons of the barons and the French, with the sumpter-horses, loaded with baggage, silver vessels, and various kinds of furniture and utensils, all which fell into their possession without opposition. Having then plundered the whole city to the last farthing, they next pillaged the churches throughout the city, and broke open the chests and store-rooms with axes and hammers, seizing on the gold and silver in them, clothes of all colours, women’s ornaments, gold rings, goblets, and jewels. Nor did the cathedral church escape this destruction, but underwent the same punishment as the rest, for the legate had given orders to the knights to treat all the clergy as excommunicated men, inasmuch as they had been enemies to the church of Rome and to the king of England from the commencement of the war; Geoffrey de Drepinges precentor of this church, lost eleven thousand marks of silver. When they had thus seized on every kind of property, so that nothing remained in any corner of the houses, they each returned to their lords as rich men, and peace with king Henry having been declared by all throughout the city, they ate and drank amidst mirth and festivity. This battle, which, in derision of Louis and the barons, they called ” The Fair,” ….. Many of the women of the city were drowned in the river, for, to avoid insult, they took to small boats with their children., female servants, and household property, and perished on their journey ; but there were afterwards found in the river by the searchers, goblets of silver, and many other articles of great benefit to the finders ; for the boats were overloaded, and the women not knowing how to manage the boats, all perished, for business done in haste is always badly done.”

The Name

The battle earned the name “The Lincoln Fair” probably because of the amount of plunder gained by the victorious English army.

© James Rye 2023

Sources

- Appleby, J.T. (1959) John, King of England (1167-1216), Knopf

- Asbridge, T. (2015) The Greatest Knight: The Remarkable Life of William Marshall, the Power Behind Five English Thrones, Simon & Schuster

- Bennett Connolly, S. (2023) King John’s Right Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de La Haye, Pan & Sword

- Giles, J.A. (1849) Roger of Wendover’s Flowers of History Vol II, Henry G. Bohn

- Grigg, E. (2019) Lincoln and the Magna Carta, Ed’s Music Lincoln

- Hanley, C. (2016) Louis: The French Prince Who Invaded England, Yale University Press

- Hanley, C. (2023) Two Houses: Two Kingdoms (A History of France and England 1100-1300), Yale University Press

- Hanley, C. (2024) 1217: Three Battles That Saved England, Osprey

- Hillen, H.J. (1907) History of the Borough of King’s Lynn, Vol.1, EP Publishing Ltd.

- Jones, D. (2013) The Plantagenets: The Kings Who Made England, William Collins

- Jones, D. (2015) In the Reign of King John: A Year in the Life of Plantagenet England, Head of Zeus Ltd.

- Morris, M. (2015) King John: Treachery, Tyranny and the Road to Magna Carta, Penguin Books

- Starkey, D. (2015) Magna Carta: The True Story BehindThe Charter, Hodder & Stoughton

- Vincent, N. (2020) John: An Evil King?, Penguin Books

- Warren, W.L. (1961) King John, Eyre & Spottiswoode

- Weir, A. (2020) Queens of the Crusades: Eleanor of Aquitaine and Her Successors 1154-1291, Vintage

Websites

- http://historiclincolntrust.org.uk/battle-of-lincoln-20th-may-1217/

- https://historytheinterestingbits.com/2017/05/20/the-lincoln-fair-the-battle-that-saved-england/

See Also

Book a Walk with a Trained and Qualified King’s Lynn Guide Through Historic Lynn.

[…] See also: The Battle of Lincoln Fair […]

[…] The Battle of Lincoln Fair […]

[…] and subsequent popes offered indulgences on the occasion of the later Crusades. (At the Battle of Lincoln Fair in 1216 the papal legate, Guala, absolved the Royalist army of all their sins committed since […]

[…] See also: Saving the King: the Second Battle of Lincoln […]