Imagine the largest 60‑metre spire in the town smashing into the nave.

On Tuesday 8 September 1741, the town of King’s Lynn was battered by a powerful storm that tore through its medieval fabric, damaging homes, churches, and civic buildings. It marked a picotal point in the history of the town.

King’s Lynn A Lost Lantern

In the sixteenth century, King’s Lynn citizens walking down High Street (then called Briggate) towards the Saturday Market Place would have been aware of a very impressive structure above St Margaret’s Church. On the roof of the church was a “lantern” – a feat of medieval engineering fusing timber, lead, and light, creating another (less heavy) tower in the middle of the church. A few of Lynn’s parishioners prided themselves in knowing that this structure was very similar to the famous lantern on the great Ely Cathedral just down the road.

But any King’s Lynn citizen walking the same route today and looking up will be greeted by nothing but a truncated, flat, stone structure. They might be forgiven for thinking that someone has put a helicopter landing pad on top of the church.

What happened to the lantern?

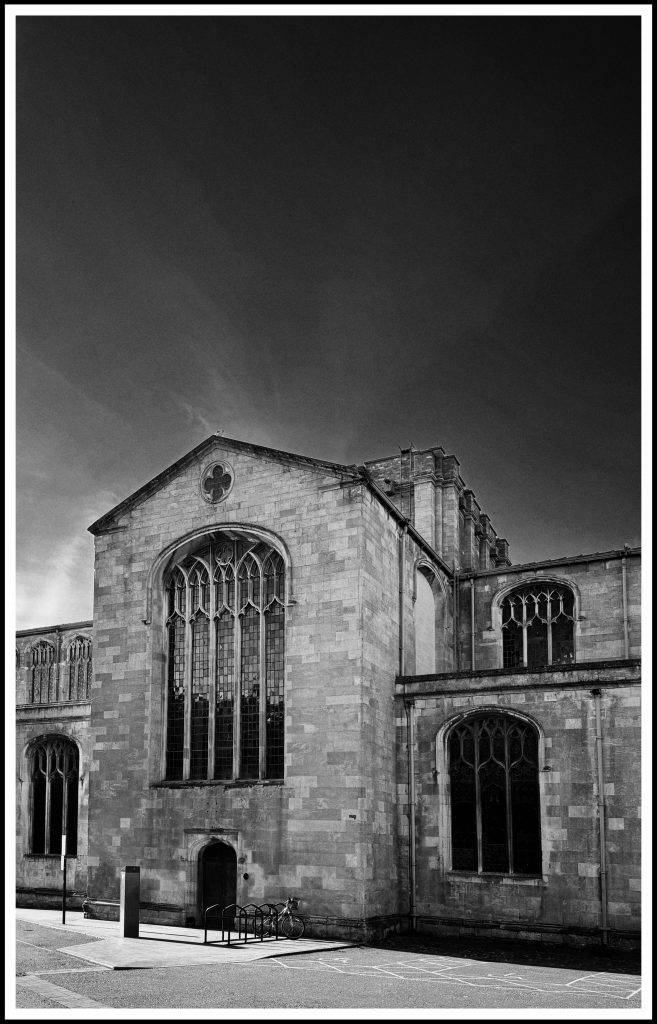

Photo © James Rye 2025

1741 Storm: Slates, Spires, and Shipwrecks

On Tuesday 8 September 1741, the town of King’s Lynn was battered by a powerful storm that tore through its medieval fabric, damaging homes, churches, and civic buildings. This “great gale” carved a narrow but devastating path across Huntingdonshire and the Fens before unleashing its fury on King’s Lynn. While it did not cause widespread loss of life, its impact on the town’s built environment was extensive – and in some cases long-lasting. According to one eyewitness writing that same week, “a most violent storm of wind and rain hath torn off roofs, shattered glass and timber, and brought much alarm upon the town.”

The 1741 Storm Itself

The storm came on suddenly during 8 September. Local records do not report thunder or lightning, but a long gale of high wind and heavy rain lasting several hours. The direction was likely from the east or south-east, based on where the damage was concentrated. This would have hit the town broadside, straight off the Wash.

The Norwich Gazette of 12 September 1741, reporting the event just days later, stated:

“On Tuesday morning last this town suffered greatly from a tempestuous wind, which brake in upon the roofs of many houses, carried away stacks, slates and timbers, and did great hurt to our public buildings.”

1741 Storm: Damage to Major Buildings

St Margaret’s Church (now King’s Lynn Minster)

The fiercest and most thoroughly recorded destruction wrought by the storm happened to St Margaret’s Church. The gale brought about the collapse of the church’s soaring 60-metre spire on the south-west tower. It crashed spectacularly through the nave, shattering the central lantern and causing widespread damage throughout the building. Both the main clock, which had presided over the east end of the nave since 1681, and the distinctive moon clock on the south-west tower, were either obliterated or gravely damaged in the disaster. (The moon phase clock has been replaced with a twentieth century replica.)

Accounts from vestry records, corroborated by reports in the Norwich Gazette, reveal further devastation: the roof of the south transept was partially torn away, with large sections of lead and timber wrenched free, and several intricate traceried windows entirely destroyed.

Contemporary churchwardens’ accounts from the Michaelmas quarter detail payments issued in the aftermath for “ye repairing of ye great south window broken in the storm,” and for “lead and iron work about ye roof carried away by the wind.” The mason Robert Armes was swiftly contracted to shore up the compromised buttresses of the transept as an emergency measure.

Inside, wind and rain forced their way through shattered windows, scattering debris across the nave and south aisle. Thankfully the sixteen misericords, dating from 1370–1377 and featuring intricate carvings such as the head of Edward the Black Prince, survived intact. For weeks, Sunday services continued in a cordoned-off area while repairs slowly advanced.

The scale of devastation necessitated a major campaign of rebuilding and remodelling. Both George II and Sir Robert Walpole contributed £1,000 each toward the restoration, whose costs mounted to an estimated £8,000. The full restoration money could not be raised and neither spire nor lantern was ever replaced. Repairs stretched into the following decade, culminating in the commissioning of a grand new Snetzler organ (1754), symbolic of renewal and resilience.

St Margaret’s proximity to the river meant that it was no stranger to high tides and floods, though there is no mention of tidal flooding damage specific to the 1741 storm.

Trinity Guildhall

The building known today as King’s Lynn Town Hall – then called the Trinity Guildhall – suffered substantial roof damage. Borough minutes from 12 September 1741 record that slates and lead were torn from the north-east slope, facing the Market Place. An immediate payment of £11 12s. 4d. was approved “for repair to the roof damaged by the storm.” Carpenters were sent to shore the wall plate and replace exposed timberwork.

St Nicholas Chapel

England’s largest chapel of ease also had its spire destroyed by the storm. This spire was a replacement for an earlier one that was lost to the elements. The 1741 destruction of the second spire led to the construction of a third “spire” – what was described as “a kind of wooden extinguisher stuck on to be seen at sea”. This third one was a functional but less elegant solution for the needs of sailors. This replacement remained until 1854, when it was removed due to concerns about its stability, and the chapel went without a spire until Sir George Gilbert Scott’s design was added in 1869.

The Custom House and South Quay

The Custom House, built in 1683 to oversee maritime trade, had several upper windows shattered by flying debris. Its distinctive weather vane – one of the oldest in Norfolk – was twisted out of true. Interior rooms used by customs officials were water-damaged and closed temporarily. The Corporation Warehouse, adjoining it, lost part of its tiled roof.

Across the quay, damage was visible all along the Fisher Fleet and Purfleet Quay. A section of the Fleet wall collapsed, and goods stored along the quayside – mostly timber and wool – were scattered or ruined. Borough labourers cleared debris from the Purfleet by order of the Assembly.

1741 Storm: Residential and Street-Level Damage

Damage to private dwellings was reported across Lynn, but was worst in:

- All Saints’ Street

- Blackfriars Street

- Church Street

- Boal Street

- Grubb’s Entry and Page’s Yard

Dozens of houses lost chimney stacks, roof tiles, or whole portions of their upper storeys. This was particularly true on Tuesday Market Place, Queen Street, and Church Street. In some cases, rain penetrated through broken windows and lifted tiles, ruining bedding, books, and stored goods. In Friars’ Lane, a small barn roof was entirely lifted off its walls and blown into a neighbouring garden.

Temporary repairs using tarpaulin and salvaged timber are mentioned in both church and borough accounts. For poorer residents, the storm meant weeks of disruption and financial loss.

1741 Storm: Shipping and Maritime Losses

Despite the storm’s ferocity, the tide was low, which helped prevent flooding. However, Lynn’s maritime economy suffered:

- A collier brig was torn from its moorings near the Bentinck Dock and ran aground.

- A Dutch wherry, anchored in the Fisher Fleet, capsized and drifted upriver. It was later recovered near South Wootton, with its mast snapped.

- A coastal sloop from Rotterdam was beached near Wolferton.

Three sailors drowned during the storm. A note in St Margaret’s burial register dated 10 September records:

“A Dutch lad, found drowned after ye late storm, buried by parish order.”

This confirms at least one body was brought ashore and buried in Lynn itself.

1741 Storm: Civic and Religious Response

On 9 September, the borough assembly met to assess the storm’s impact. Its minutes record concern over:

- Public buildings: Guildhall, school, market structures

- Port functions: Collapsed quay walls and lost cargo

- Damage to poorer households

A special fund of £20 was allocated for urgent repairs. Carpenters and labourers were hired to remove dangerous debris and secure damaged roofs.

On Sunday 13 September, churches across the town held thanksgiving services. At St Margaret’s, the preacher took his text from Nahum 1:3 – “The Lord hath his way in the whirlwind and in the storm.” The church was still partly scaffolded, and pews were cordoned off. Collections were taken to assist the poor, and extra bread was distributed from the mayor’s fund.

Conclusion

The storm of 8 September 1741 was not a national disaster, but it was one of the worst weather events in Lynn’s recorded history. It damaged the town’s largest church, disrupted its port, and left its civic leaders scrambling to stabilise key buildings. While few lives were lost, the cost in repair and hardship was considerable, especially for poorer residents. And, in a few places, the storm’s damage significantly changed the look of the town.

Sources

- Norwich Gazette, 12 and 19 September 1741

- King’s Lynn Borough Assembly Minutes, KL/C7/21, 8–12 September 1741 (KLBA)

- St Margaret’s Churchwardens’ Accounts, PD 39/72 (NRO)

- Parish Register, St Margaret’s, burial entry for 10 September 1741

- William Richards, History of Lynn (1812), vol. II, pp. 314–315

- William Taylor, Annals of King’s Lynn (1850), p. 121

- Norfolk Quarter Sessions, C/S 1/25 (NRO)

[…] See also: The King’s Lynn Storm of 1741 […]