The Boy, the Bishop, and the Blood Libel

The story of William of Norwich, and the role played by Bishop William Turbe, reflects the twelfth-century hardening of Christian suspicion towards Jews. Bishop Turbe’s endorsement gave the story its authority. The outcome was not simply a local legend but the first fully articulated ritual murder accusation in medieval Europe, but it became a narrative pattern that would be repeated from Lincoln to Trent and beyond.

William of Norwich: A Boy in a Troubled City

In 1144, the body of a boy named William, probably about twelve years old and apprenticed to a Norwich skinner, was discovered in Thorpe Wood. He had disappeared close to Easter. When found, his corpse showed marks that some observers described as violent injuries, although the evidence cannot now be reconstructed with any certainty. What happened to him is unknown. There were no witnesses, no reliable testimony, and no recorded suspects.

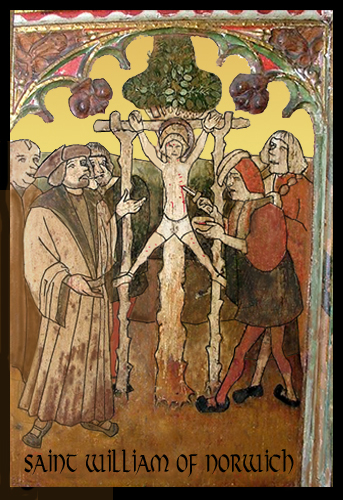

Image from Holy Trinity church, Loddon, Norfolk

Image © J.J.Cohen https://www.inthemedievalmiddle.com/

Norwich at the time was a busy and sometimes fractious city. It supported a small Jewish community, established with royal permission in the late eleventh century. As in most English towns, Jews acted partly as moneylenders, filling an economic role barred to Christians by canon law. This position made them valuable to the Crown but also vulnerable to local resentment. Rumours about ritual violence against Christians had begun to circulate in parts of France and Germany in the decades before 1144, although nothing identical to the Norwich story had yet reached England in written form.

When William’s body was found, some locals were quick to point the finger at their Jewish neighbours. The sheriff, John de Chesney, carried out what investigation he could and chose not to bring charges. His decision effectively quashed the matter for the moment. William was buried quietly, and no one at this stage attempted to cast him as a martyr or saint.

Thomas of Monmouth: The Revival of a Rumour

The story emerged again several years later, driven largely by the ambitions of Norwich Cathedral Priory. In the mid-1140s a monk named Thomas of Monmouth arrived at the priory. Over the following decade he collected hearsay, shaped testimonies to fit a narrative, and wrote a long hagiographical work, The Life and Passion of William of Norwich. It is divided into seven books and presents William as a pious child, betrayed, tortured, mocked, and killed in a sequence meant to echo the Passion of Christ.

None of Thomas’s colourful detail has any independent verification. His writing belongs firmly to the genre of miracle-laden saints’ lives. Yet it is within this text that the first complete ritual murder accusation appears in European literature. Thomas claimed that Jews across Christendom held a secret council each year to select a Christian child for sacrifice. Norwich, in his telling, was the chosen place in 1144.

What gave the work lasting influence was not its style nor even its content but its reception among the clergy. The most important supporter of Thomas’s project was the diocesan bishop.

William Turbe: a Bishop with Local Aims

William Turbe, (sometimes known as William de Turbeville) was born around 1095 and was a Benedictine monk at Norwich long before becoming bishop in 1146. He served as prior of the cathedral monastery, gaining experience in administration during a period of fire damage, rebuilding, and political unrest. His election as bishop came after the deposition of his predecessor, Bishop Everard, during the final phase of the civil war between Stephen and Matilda.

Turbe’s long episcopate, which lasted until his death in 1174, was a period of consolidation. He shored up diocesan authority, secured and confirmed estates, and navigated between shifting royal powers. Although not a figure of national fame, he was respected as a learned churchman.

Turbe played an important part in the history of Bishop’s Lynn (later to become King’s Lynn), and his influence there is still very much in evidence today. He saw the extension of the original town beyond the boundary of the Purfleet, the founding of St Nicholas Chapel – what was to become the biggest Chapel of Ease in the country – and the very large Tuesday Market Place.

From a national perspective, his most visible, and in some ways most enduring, act was his sponsorship of the cult of William of Norwich. He did not invent the story, but without his support it is unlikely that the tale would have moved beyond rumour. He is partially responsible for one of the earliest European accounts of the infamous blood libel myth – that Jews murdered Christian children and used the blood of these sacrificed gentiles in their religious ceremonies.

Turbe authorised moving William’s body from its initial grave to a more honourable position within the cathedral precincts. He intervened when other clergy objected to the growing claims of sanctity and upheld the view that William’s death had been martyrdom. His endorsement allowed William’s cult to grow, and in doing so gave new impetus to Thomas of Monmouth’s literary venture.

Turbe and the Monks Build a Saint: Translations, Miracles, and Publicity

Saints’ cults in medieval England did not arise spontaneously. They were shaped through a combination of ritual actions, narrative reinforcement, and material investment. Turbe and the monks of Norwich carried out several of these steps.

Translations and shrine building

William’s remains were translated multiple times to increasingly prestigious locations. The final move placed him in a specially created chapel near the site where his body had been found. These actions invited the faithful to view William as a martyr whose sanctity demanded visible honour.

Miracle stories and local devotion

Reports of healing and intercession began to circulate. Mothers seeking aid for sick children were particularly drawn to the shrine. Offerings increased, giving the priory a modest but welcome source of income. Although the cult never achieved the status of national pilgrimage centres such as Canterbury or Durham, it became a recognised feature of Norfolk’s devotional landscape.

Hagiography and persuasion

Thomas of Monmouth’s narrative was encouraged and protected by Turbe. The text’s dramatic episodes functioned as a tool of persuasion, helping to justify the cult internally among the monks and externally among the laity. Its message was clear: William had died a holy death, and the Jews of Norwich bore responsibility.

Judicial theatre

Turbe also played a role in public hearings and ecclesiastical disputes related to the story. Although no formal prosecution of the Jews occurred, his willingness to summon Jewish residents for questioning lent the accusation a level of clerical authority. It contributed to a lingering suspicion that would later be revived in future crises.

A Pattern Takes Shape: the Wider Consequences

The story of William of Norwich did not end at the cathedral doors. Over the next century it became the template for similar accusations elsewhere in England. The case of Little Hugh of Lincoln in 1255 is the most notorious later example, but there were others at Bury St Edmunds, Gloucester, and Winchester.

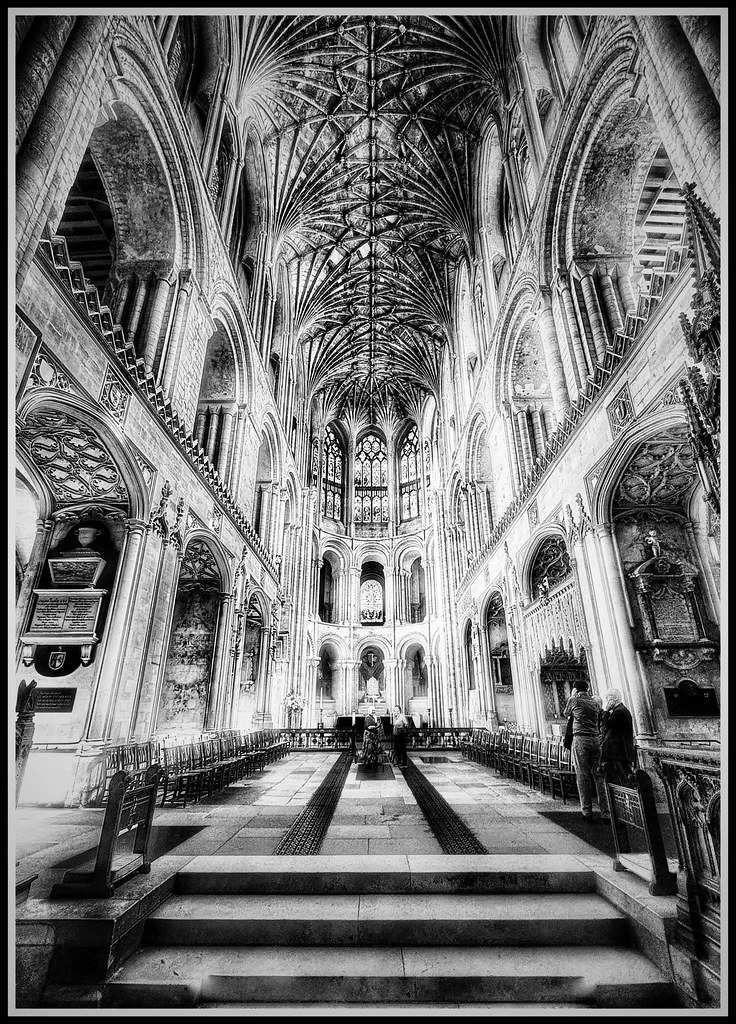

Photo © James Rye 2024

The narrative structure was always strikingly similar. A missing child. A body found in ambiguous circumstances. A rumour of Jewish involvement. A monastic writer ready to construct a martyr’s life. A shrine. A stream of miracle stories. And in many cases, increasingly punitive attitudes toward the local Jewish communities.

Norwich’s example helped establish this pattern. It appeared at a moment when Christian anxieties about Jews were growing, influenced by crusading rhetoric, economic tensions, and theological hostility. William’s cult provided the first full script.

The long-term impact on English Jews was severe. Although the Norwich community escaped immediate violence in 1144, the suspicions that Thomas and Turbe endorsed helped to normalise a belief that Jews were capable of ritual murder. The thirteenth century saw harsher legislation, rising hostility, and repeated episodes of mob violence. There was a pogrom of the Jews in Bishop’s Lynn in 1190. The expulsion of the Jews in 1290, ordered by Edward I, came at the end of this trajectory.

The Fading of a Cult

William’s shrine never became a major centre of pilgrimage, and by the later Middle Ages his cult had lost much of its vitality. After the expulsion of the Jews, the story’s polemical force diminished. By the sixteenth century, interest in William had largely disappeared, though Thomas of Monmouth’s manuscript survived in the cathedral library.

It was rediscovered by antiquaries in the nineteenth century, and since then historians have treated the case as a key moment in the development of anti-Jewish myth in Europe.

Assessing the Evidence Today

Modern scholarship is unanimous on several points.

- There is no historical basis for the accusation against the Jews.

- The hagiography is a work of polemic, shaped by monastic ambition.

- William’s death cannot be confidently explained, but accidental death or localised crime are much more plausible than ritual murder.

- The cult served the interests of the cathedral priory by raising its profile and providing a source of income.

- The story became a model for later accusations with far more tragic consequences.

Turbe’s role was pivotal. His support transformed an unproven rumour into an authorised cult. He acted within the conventions of his age; bishops across Europe promoted local saints as a means of strengthening ecclesiastical identity and authority. The difference in Norwich is that the cult rested on a claim that harmed a real community of living people.

The Origin of Lies

The death of William of Norwich might have remained an obscure local mystery. Instead, it became a defining moment in medieval English religious culture and the starting point of a tradition of hostile storytelling that would influence Europe for centuries.

The events of 1144 cannot be undone, but understanding them helps explain the origins of prejudice and the mechanisms by which fear becomes accepted truth.

© James Rye 2025

See also The Jews of King’s Lynn

Book a Walk with a Trained and Qualified King’s Lynn Guide Through Historic Lynn

Further Reading

- E. M. Rose, The Murder of William of Norwich: The Origins of the Blood Libel in Medieval Europe, Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Miri Rubin, Gentile Tales: The Narrative Assault on Late Medieval Jews, Yale University Press, 1999.

- Miri Rubin (trans.), The Life and Passion of William of Norwich, Penguin Classics, 2014.

- Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_de_Turbeville