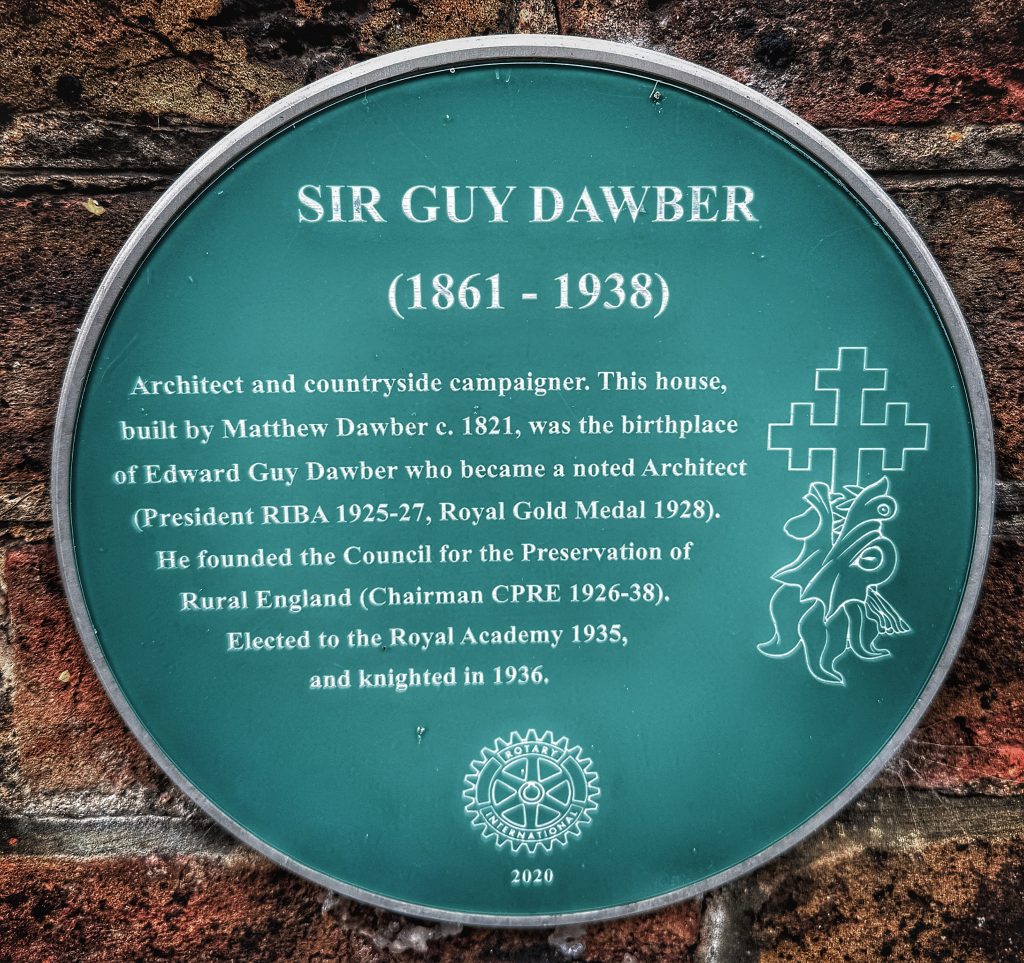

Sir Edward Guy Dawber

Sir Edward Guy Dawber is not a household name in King’s Lynn, yet he deserves far more recognition locally than he receives. Born in the town in 1861, he went on to play an important part in the Arts and Crafts movement, earned a knighthood, and eventually chaired the Council for the Preservation of Rural England. His buildings are scattered across the Cotswolds, Wiltshire and Kent, rather than around the Wash, but his earliest influences were firmly rooted in the streets of Lynn.

Sir Edward Guy Dawber: A Lynn Childhood Shaping an Architectural Imagination

Dawber grew up at a time when King’s Lynn still carried a strong sense of its earlier prosperity. Many of the town’s older merchant houses remained intact. The Customs House sat as it had since 1683. The minor courts and yards showed their seventeenth and eighteenth-century brick and stonework. Later writers recalled Dawber reminiscing about how he wandered through these spaces as a boy, picking up architectural cues almost without noticing.

He once remarked that he knew every street and every detail of the Custom House. That building in particular, with its Dutch-influenced proportions mingled with English classical ornament, appears to have become something of a touchstone for him. Observers of his mature work often comment on how carefully he handled details such as cornices, chimneys and gable ends. None of these elements in his country houses look copied from Lynn, but they do feel as though they come from someone steeped early in a town where the local vernacular had depth and variety.

The same is true of the broader architectural character of Lynn. Dawber grew up in a place where Flemish gables, Renaissance brickwork and Georgian façades sat together in a fairly harmonious cluster. It may be stretching the point to say Lynn shaped his entire career, but it certainly helped him develop an eye for domestic architecture that remained sensitive to local materials and proportions.

Photo © James Rye 2025

Sir Edward Guy Dawber: Training in King’s Lynn and the Journey Outward

Dawber was articled to the King’s Lynn architect William Adams for four years. We know less about Adams than about his more famous apprentice, but the arrangement gave the young man a solid grounding in practice: site work, plans, surveying and client discussions. By the early 1880s he felt ready to move on, first to Dublin to work under Thomas Newenham Deane, and then to London where he joined the office of Ernest George and Harold Peto. Both were distinguished architects whose practices offered an excellent environment for a promising student.

He also studied at the Royal Academy Schools. This mixture of provincial training and London mentoring gave him confidence to open his own practice around 1890. He chose Bourton-on-the-Hill in the Cotswolds rather than a city centre, which hinted at the direction his career would take.

Sir Edward Guy Dawber: A Career Rooted in the Arts and Crafts Movement

Dawber soon became recognised for designing country houses that worked naturally with their settings. His buildings show a strong awareness of local stone, roof pitches and rural settlement patterns. He avoided theatricality and tended instead toward homes that felt grown from the landscape rather than imposed upon it.

Examples include Nether Swell Manor and the buildings at Eyford. Conkwell Grange, completed in 1907, is often cited as an especially successful demonstration of his approach. These designs rarely seek to dominate. Instead they give the impression of being sensible, carefully balanced homes with thoughtful details and craftsmanship of a very high order.

His interest in vernacular buildings extended into scholarship. His 1905 study of Cotswold cottages and farmhouses remains an informative survey, supported by measured drawings and direct observation. The book shows that Dawber valued rural architecture not simply as a set of stylistic cues but as a living tradition worth recording and protecting.

countrylife.co.uk

Sir Edward Guy Dawber: Leadership, Conservation and National Recognition

By the 1920s Dawber’s reputation was secure. His colleagues elected him President of the Royal Institute of British Architects for the years 1925 to 1927, and he received the Royal Gold Medal for Architecture in 1928. He also became the first chairman of the Council for the Preservation of Rural England, a sign of his concern for landscape and settlement patterns at a time when motor transport and speculative building were beginning to alter the English countryside.

His civic and conservation work attracted considerable respect, and in 1936 he was knighted. Although his practice continued to work largely with domestic buildings, he did take on the Reptile House at London Zoo, a commission that required a more public architectural language yet still shows his steady handling of materials and form.

He died in 1938, leaving behind a body of work that helped define a particular strand of Arts and Crafts design. His influence is gentler and less widely celebrated than that of Lutyens, but his contributions remain significant for anyone interested in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century architecture.

Sir Edward Guy Dawber: The Lynn Connection Revisited

What, then, is Dawber’s legacy in King’s Lynn? Physically, very little. His mature practice lay elsewhere, and no major works survive in his home town. Yet his professional identity was tied quietly but unmistakably to Lynn. Biographical accounts note his birthplace, and architectural journalists of the mid-twentieth century drew attention to the part Lynn’s streets played in forming his architectural sense.

© James Rye 2025

Book a Walk with a Trained and Qualified King’s Lynn Guide

Source

- “Edward Guy Dawber: Obituary.” The Architects’ Journal 87, no. 2254 (28 April 1938): 643–44. https://usmodernist.org/AJUK/AJUK-1938-04-28.pdf.

- “Guy Dawber: An Appreciation.” The Architects’ Journal 98, no. 2554 (24 June 1943): 471–72. https://usmodernist.org/AJUK/AJUK-1943-06-24.pdf.

- “Dawber, Edward Guy (1861–1938).” AHRNet. https://architecture.arthistoryresearch.net/architects/dawber-edward-guy.

- “A Brief History of CPRE.” CPRE: The Countryside Charity. https://www.cpre.org.uk.

- “Edward Guy Dawber (1861–1938).” Parks and Gardens UK. https://www.parksandgardens.org/people/edward-guy-dawber.

- “Conkwell Grange, Wiltshire: Edward Guy Dawber’s Gold Medal Project.” RIBA Journal. https://www.ribaj.com/buildings/edward-guy-dawber-riba-gold-medal-conkwell-grange-wiltshire-arts-crafts.

- “Guy Dawber: Architectural Drawings and Country Life Features.” Rostron & Edwards Image Archive. https://www.rostronandedwards.com.

- “Edward Guy Dawber.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guy_Dawber.

- “List of People from King’s Lynn.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_people_from_King%27s_Lynn.