The Medieval “Good Death”: Faith, Ritual, and Reputation

To the medieval mind, a “good death” was not simply a matter of dying peacefully in bed. It was an achievement. The Latin phrases mors bona or mors felix carried great weight: this was a death that crowned a life of Christian duty, correct belief, and careful preparation.

To die well was to die rightly – in harmony with God, in order with society, and with a soul fit for judgement.

The ideal was not abstract. It shaped sermons, parish handbooks, wills, and even village memory. A good death secured not only the fate of the soul but also the reputation of the household.

Armouring the Soul

By the twelfth century, preachers were insisting that death was the moment when faith would be tested most fiercely. The Speculum ecclesiae of Edmund of Abingdon, for instance, urged Christians to “watch over your last hour as if the enemy lay in wait.” The idea was reinforced by later pastoral manuals and by the fifteenth-century Ars moriendi, which treated the last moments of life as a kind of trial in which angels and demons contended over the soul.

To face it properly, spiritual readiness was essential. The “last rites” – confession of sins, reception of the Eucharist and anointing with holy oil – were prescribed as the soul’s armour. These sacraments, as Eamon Duffy has shown, were not marginal but central rituals in parish life (Duffy, Stripping of the Altars, pp. 301–5). Ideally, the dying remained conscious long enough to renounce the devil, forgive others, and commend their soul to God.

The “bad death” lurked as a terrifying opposite: sudden, violent, or unprepared, with no time for confession or absolution. That fear was sharpened by outbreaks of plague, when the priest might not arrive in time. Rosemary Horrox’s Black Death documents the trauma of such deaths, and the desperate attempts to improvise rites in the absence of clergy.

Deathbeds as Stages

Dying was rarely private. The presence of family, neighbours, and clergy meant that the deathbed became a kind of stage where faith, generosity, and reconciliation were performed before witnesses. Barbara Hanawalt records examples of peasants in manorial courts recalling how they had attended a neighbour’s deathbed to hear a final settlement or act of forgiveness (Ties That Bound, pp. 181–3).

Last wills were often declared orally in these moments, with clerks or witnesses writing them down later. They were more than legal instruments: they were acts of public reconciliation. Debts were admitted, wrongs corrected, enemies forgiven. Such displays reassured the household and offered a measure of peace to the community.

Charitable gifts also mattered. Bequests to parish churches, hospitals, or chantries not only purchased prayers for the soul but served as visible proof of piety and status. Beat Kümin’s work on parish life shows how these benefactions tied the individual to the worshipping community long after death (Shaping of a Community, pp. 45–8).

Angels, Demons, and the Art of Dying

The Ars moriendi, produced in the early fifteenth century, made explicit what had long been preached. Born in the shadow of plague and war, these manuals instructed the dying to resist temptations to despair, impatience, pride, or greed, and to trust instead in divine mercy.

Illustrated block-book editions, cheap enough to be widely circulated, left nothing to the imagination. In one striking image, demons tempt the dying with bags of gold or whisper doubts about God’s mercy, while angels lean in to encourage repentance and faith. R. Emmet McLaughlin notes that these images dramatised death as a cosmic battle in miniature (Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 22:2, pp. 260–3).

This was a death imagined as warfare, the soul caught between contending forces, its victory or defeat to be sealed at the very last breath.

Life After Death – On Earth

The good death did not end at the moment of dying. Burial in consecrated ground, the tolling of bells, and a funeral Mass bound the dead to the community they had just left.

Prayers did not stop there. Anniversaries were carefully observed: obits, chantry services, and commemorations filled the parish calendar. As Peter Marshall has shown, late medieval wills in England often devoted as much space to endowing chantry priests or paying for anniversary feasts as they did to dividing property among heirs (Beliefs and the Dead, pp. 53–8). The living were expected to keep the memory of the dead alive, and the dead, in turn, were expected to intercede for their benefactors in purgatory.

To modern readers, the concern with perpetual masses or candles may seem excessive. To contemporaries it was practical: a means of keeping the soul supported, and a way of knitting the dead into the rhythms of parish life.

When Ideals Collided with Reality

For all its reassurance, the ideal of the “good death” was often out of reach. Plague, war, famine, and accident could strike suddenly, cutting short any chance to stage a proper death. The unpredictability of life made preparation all the more urgent. Sermons rang with the warning: “Be prepared, for you know not the hour” (Matthew 24:44).

This anxiety left deep marks. Some men drew up their wills long before illness overtook them, to make sure nothing was left undone. Others endowed masses in advance, fearing they might die far from home. Even so, countless deaths fell short of the ideal, leaving survivors to negotiate how best to remember and pray for them.

John Hatcher’s imagined detailed account of the Black Death affecting a village in Suffolk estimates that at one point 50 people a day were being killed by the plague. In London over 200 people a day were being buried. Some victims were far too sick at the end to receive the Eucharist, even if it was offered to them. The shortage of priests meant that almost anyone (even women) could hear confession. Hatcher describes the real anxiety faced by relatives who feared that a “good death” had not been achieved.

From a modern perspective, the whole structure can seem rigid, even theatrical. Yet to those who lived within it, the good death was a promise. It gave order to life’s most uncertain moment and offered hope that the end could be faced with meaning and dignity.

John Baret’s Good Death

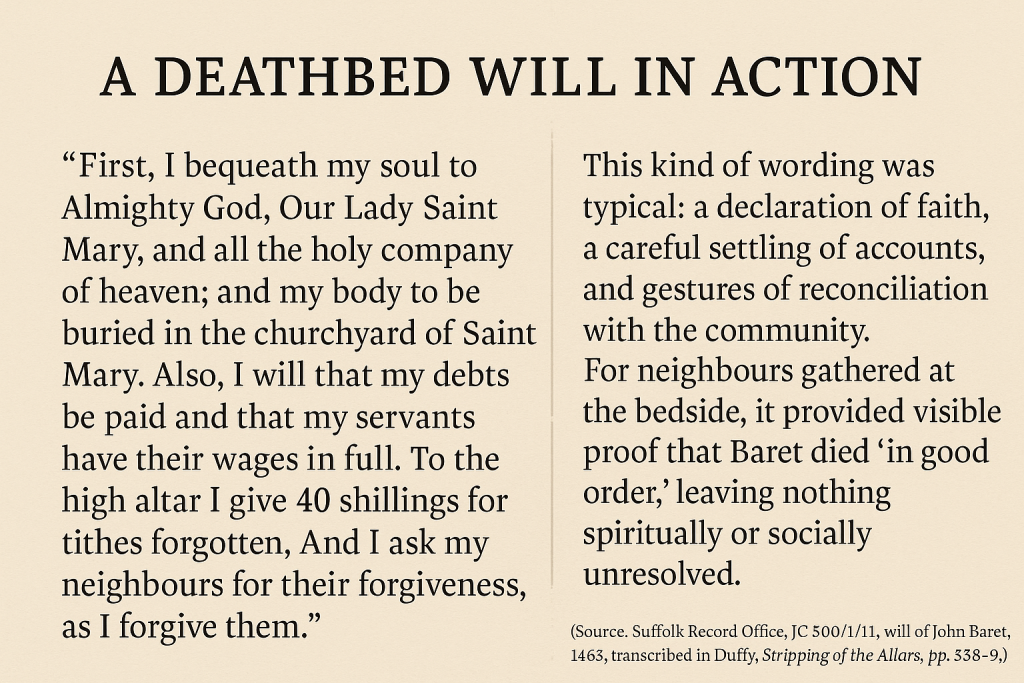

John Baret, who died in 1463, was a prominent and affluent cloth merchant, whose prosperity and social connections placed him among the elite of Bury St Edmunds. Notably, he likely acted as a patron to the medieval poet John Lydgate. We don’t have details of his deathbed scene, but his will shows he was trying to demonstrate a good death.

Full Spiritual Preparation

Baret’s will opens conventionally but emphatically with the surrender of his soul to God, the Virgin Mary, and the saints. He made provision for Masses, prayers, and offerings to the high altar “for tithes forgotten.” This was exactly the kind of spiritual housekeeping preached from pulpits: make peace with God, clear your conscience, and ensure no sins remain unsettled.He also specified his funeral liturgy in detail – not as vanity, but as a way to guarantee the sacraments, processions, and prayers that safeguarded the soul’s passage.

Public Witness and Community Order

A “good death” had to be visible and orderly. Baret’s will ensured that neighbours, clergy, and guild brothers would attend, and that his funeral was staged as a public affirmation of faith. The lavish procession, with symbolic figures representing Christ’s wounds and the Virgin’s joys, dramatised the theology of redemption for everyone present.

By arranging such a display, Baret left no doubt that he died as a Christian in good standing. His neighbours could vouch for him, and the record of his will served as written proof of a death “in good order.”

Charity and Reconciliation

Generosity at the deathbed was a hallmark of a good death. Baret distributed devotional items, gowns, rosaries, rings, and cups — gifts that spread goodwill and reinforced social ties. He endowed priests, chantries, and charitable works.

Even his house (Baret House in Chequer Square) was to continue in religious use, with a chapel and a “spinning house” to support clergy and, perhaps, local women. These gestures demonstrated humility and care for both the poor and the parish, echoing the medieval teaching that almsgiving helped speed the soul through purgatory.

Acceptance of Mortality

The cadaver tomb he commissioned is a sermon in stone. Shown as a decaying corpse, Baret presented himself not as a proud merchant but as a stark reminder of human frailty. Its inscription – “He that will sadly behold me with his eye may see his own morrow and learn to die” – was not just personal; it was communal teaching.

By turning his grave into a lesson, he aligned himself with the medieval ars moriendi tradition: death as both an ending and an act of witness.

Ordering of Household and Memory

Baret’s will was remarkably detailed – over 30 pages long. He ensured debts were paid, servants rewarded, and property passed on. His estranged wife received little (perhaps showing the human limits of reconciliation), but the wider household and parish were carefully provided for.

This blend of practical and spiritual preparation – tidying up worldly affairs, setting an example of generosity, and securing ongoing remembrance – was the essence of a good death.

© James Rye 2025

See also: Thomas of Lynn

Book a Walk with a Trained and Qualified King’s Lynn Guide

Further Reading

- Duffy, Eamon. The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, 1400–1580. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992.

- Hanawalt, Barbara A. The Ties That Bound: Peasant Families in Medieval England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Hatcher, John. The Black Death: The Intimate Story of a Village in Crisis, 1345-1350. London: Orion Books, 2008.

- Horrox, Rosemary (ed.). The Black Death. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1994.

- Kümin, Beat A. The Shaping of a Community: The Rise and Reformation of the English Parish, c.1400–1560. Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1996.

- Marshall, Peter. Beliefs and the Dead in Reformation England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- McLaughlin, R. Emmet. “The Artes Moriendi and the Literature of Death in the Fifteenth Century.” Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies 22, no. 2 (1992): 255–276.

- Swanson, R. N. Religion and Devotion in Europe, c.1215–c.1515. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.