In the chaos of the English Civil War, Valentine Walton (c.1592-1661/2) stood at the turbulent crossroads of loyalty, power, and principle. A Parliamentarian with deep personal ties to Oliver Cromwell – his brother-in-law – Walton was no mere footnote in history. He held command over King’s Lynn at a critical moment, steering the strategic Norfolk port through shifting allegiances. His life is a story of conviction tested by war and shadowed by tragedy.

Cromwell Family Connections

Born around 1592 into the Walton (or Wauton) family of Huntingdonshire, Valentine inherited the Manor of Great Staughton at the age of twelve from a distant kinsman, Sir George Wauton. This made him a landed gentleman at a young age. His upbringing was entrusted to Sir Oliver Cromwell of Hinchingbrooke House, uncle to the future Lord Protector.

In 1617, Walton married Margaret Cromwell, Oliver’s sister, solidifying what would become a powerful – and eventually fateful – alliance. Unlike some of the gentry who remained loyal to the Crown, Walton became increasingly aligned with Parliamentarian and Puritan causes.

His refusal to pay Ship Money in the 1630s (a tax levied without parliamentary consent) marked him out as a man of principle. His brief imprisonment only strengthened his resolve.

Valentine Walton: At the Heart of a Nation in Crisis

By 1640, Walton had entered the House of Commons as MP for Huntingdonshire, defeating a Royalist opponent backed by his own former guardian, Sir Oliver Cromwell. He quickly embedded himself in key parliamentary committees, especially those related to religion and national defence.

When the Civil War erupted in 1642, Walton acted decisively. He joined Oliver Cromwell in intercepting £20,000 worth of silver plate destined for the King from Cambridge colleges. He raised a troop of horse, joined the Earl of Essex’s army, and was captured at the Battle of Edgehill. After several months as a Royalist prisoner in Oxford, he was exchanged and resumed his military and political activities.

His role in the recapture of King’s Lynn from Royalist forces was significant. Appointed Governor, he helped secure a vital eastern port for Parliament. However, his tenure was not without controversy: accusations of demolishing an almshouse and misappropriating building materials hint at either arrogance, necessity – or political payback.

Cromwell’s Letter and Walton’s Tragedy and Resolve

Perhaps the most poignant episode of Walton’s life came in July 1644, when his son, also named Valentine, was killed at the Battle of Marston Moor. The younger Walton died from a cannon shot. Oliver Cromwell’s famous letter of condolence offers a glimpse of their shared grief:

Sir, God hath taken away your eldest sonn by a cannon shott, itt brake his legg, wee were necessitated to have itt cutt off, wherof he died.

Sir, you know my tryalls this way, but the Lord supported mee with this, that the Lord tooke him into the happinesse wee all pant after, and live for. There is your precious child, full of glory, to know sinn nor sorrow any more. Hee was a gallant younge man, exceedinge gracious. God give you his comfort. Before his death hee was soe full of comfort, that to Franke Russell and myselfe hee could not expresse itt, itt was soe great above his paine. This hee sayd to us. Indeed itt was admirable. A little after hee sayd one thinge lay upon his spirit. I asked him what that was. Hee told mee, that it was, that God had not suffered him to bee noe more the executioner of his enimies. Att his fall, his horse being killed with the bullett and as I am enformed 3 horses more, I am told, hee bid them open to the right, and left, that hee might see the rouges runn. Truly hee was exceedingly beloved in the Armie of all that knew him, but few knew him, for hee was a precious younge man, fitt for God. You have cause to blesse the Lord, hee is a glorious saint in heaven, wherin you ought exceedingly to rejoyce. Lett this drinke up your sorrowe, seeing theise are not fayned words to comfort you, but the thinge is soe real and undoubted a truth. You may doe all thinges by the strength of Christ, seeke that, and you shall easily beare your tryall. Lett this publike mercie to the church of God make you to forgett your private sorrowe. The Lord bee your strength, soe prayes your truly faythfull and lovinge brother,

Oliver Cromwell

My love to youre daughter and my cousin Percevall, sistere Desbrowe and all freinds with you.

Cromwell’s blend of personal sorrow and theological resolve reflects the emotional landscape of the time – where familial love and religious conviction were deeply entwined.

The Move from King’s Judge to Council of State

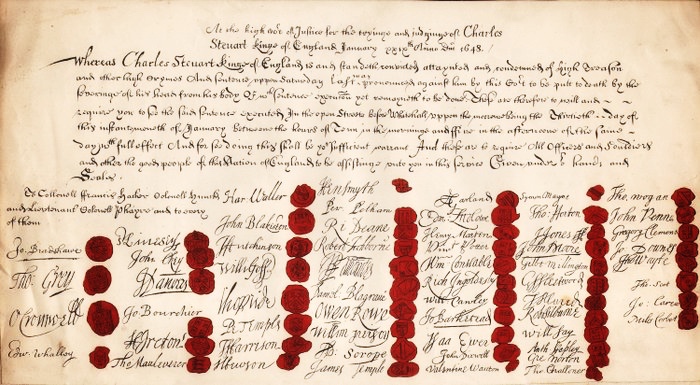

In the aftermath of Parliament’s victory, Walton became one of the judges in the trial of Charles I in January 1649. He attended nearly all sessions and signed the King’s death warrant – his name appearing in an alternative spelling, Valentine Wauton, perhaps a deliberate obfuscation.

Following the execution, he served on the Council of State and played an active role in the early governance of the Commonwealth. He also became one of the “adventurers” funding the drainage of the Fens, acquiring over 500 acres of newly reclaimed land.

Cromwell’s signature is the third down in the first column, Walton’s is the last in the fifth column, and Corbet’s (who had King’s Lynn connections) is the last on the list.

However, his support for Cromwell cooled. Walton refused appointments under the Protectorate and grew critical of its increasing authoritarianism. Though he briefly returned to Parliament during the collapse of the Protectorate in 1659, he was soon removed from public life by General Monck.

Disgrace, Flight: Walton’s Final Years

The Restoration of Charles II in 1660 sealed Walton’s fate. He was named in the Act of Attainder and his estates – including the manor of Crowland and lands in Somersham – were confiscated. Now a regicide and a hunted man, he fled abroad.

In Hanau, Germany, he briefly resurfaced as a burgess, but Royalist agents pursued him even there. Forced to move again, he died in exile – likely in Flanders – around 1661 or early 1662, aged nearly seventy. According to antiquary Anthony Wood, he spent his final days working as a gardener, revealing his identity only on his deathbed.

His second wife, Frances Pym (of another prominent Parliamentarian family), died of smallpox in Oxford a few months later.

© James Rye 2025

See also King’s Killers in King’s Lynn.

Book a Walk with a Trained and Qualified King’s Lynn Guide

Suggested Further Reading

- Hill, C. (1980) The Century of Revolution 1603–1714, Routledge

- Fraser, A. (1973) Cromwell: Our Chief of Men, Methuen

- Wedgwood, C.V. (1964) The Trial of Charles I, Collins

- Underdown, D. (1971) Pride’s Purge: Politics in the Puritan Revolution, Oxford University Press

- Withers, A. (2023), Great Staughton and Its People, Great Staughton Local History Society

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, entry on Valentine Walton (online edition)